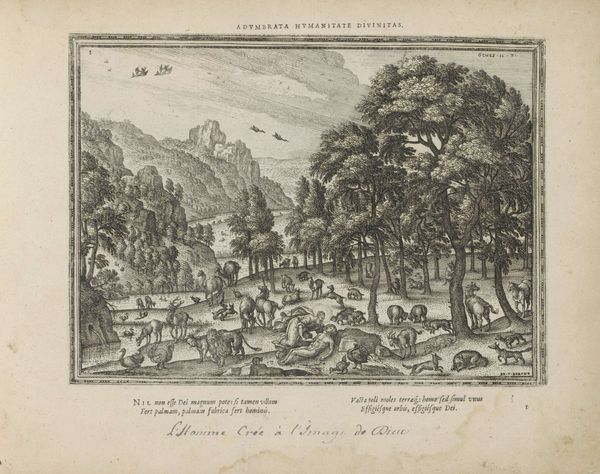

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 188 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Editor: So, here we have Pieter van der Borcht's print, "Isaak zegent Jakob," made sometime between 1582 and 1613. It's an engraving currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. I find the contrast between the interior scene and the landscape particularly striking. What do you see when you look at this print? Curator: Well, for me, the beauty here lies in understanding the process and social context. This isn't just about a biblical scene; it's about how that scene was mass-produced and disseminated through printmaking. Engraving allowed for the creation of multiple, relatively affordable images, impacting the accessibility of religious narratives for the common person. Editor: That's a great point. It shifts the focus from the artistic genius to the practical side of image-making. Do you think that shift affects the artwork itself? Curator: Absolutely. Considering the division of labor inherent in printmaking – the artist who designs the image versus the craftsman who executes the engraving – prompts us to question traditional notions of authorship. Furthermore, the materials themselves - the copperplate, the ink, the paper - speak to the economies of art production in the Northern Renaissance. Were these materials easily accessible? Who controlled their distribution? Editor: So you’re saying the material itself has cultural relevance. Almost like a mirror of society back then? Curator: Precisely. Each impression from this plate becomes a tangible artifact of a complex network involving artists, artisans, patrons, and consumers. The landscape here even feels connected to that thought – a representation of real, accessible space outside of the elite context of the home. Editor: I see what you mean. By thinking about the means of production, it makes the artwork about so much more than just the biblical story! Curator: Exactly! Considering its materiality and production transforms our understanding, moving beyond aesthetics into the realm of social and economic history. It makes the landscape not just pretty, but integral to what is shown, made and consumed. Editor: This has broadened my perspective, shifting from the aesthetic to considering how and why the work was made, impacting its meaning today! Curator: Indeed, looking at the material helps reveal the layered contexts surrounding this seemingly straightforward biblical illustration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.