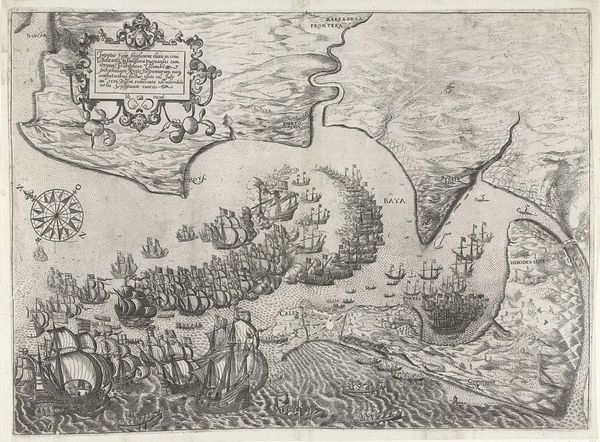

drawing, coloured-pencil, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

# print

#

landscape

#

mannerism

#

coloured pencil

#

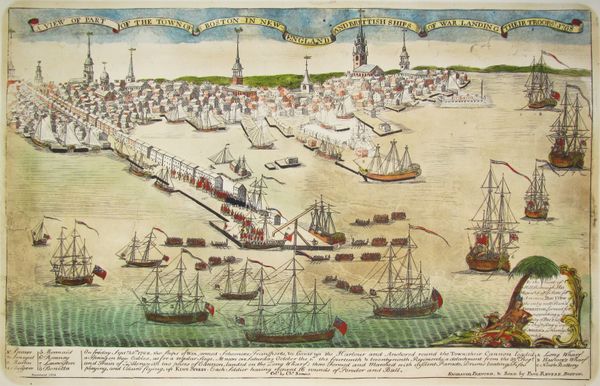

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 212 mm, width 294 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

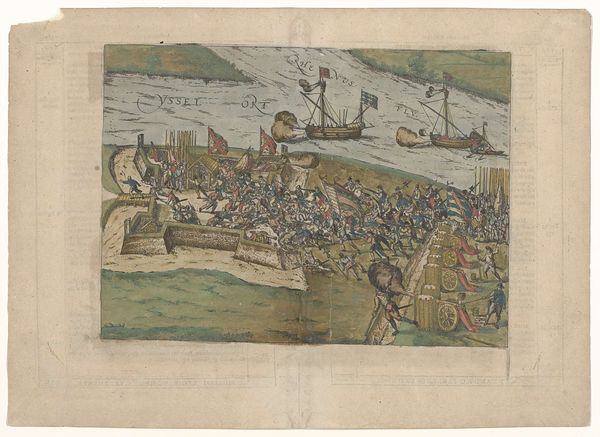

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this print titled "Fort Rammekens ingenomen, 1573," dating from around 1573 to 1575, by Frans Hogenberg, part of the Rijksmuseum collection. It appears to be a coloured engraving and drawing. Editor: It's incredibly busy. The composition crams so much in, but there's an immediacy to its depiction of battle. I'm struck by how stylized and almost naive the rendering feels despite the serious subject matter. What materials would have been used in its making? Curator: Given its nature as an engraving, the artist, Hogenberg, would have painstakingly carved the image into a metal plate. From there, the coloured pencil would add the details. Consider how the materials shape our perception; this wasn't designed as a precious painting for private viewing. It was meant for reproduction, dissemination and circulation among the masses, a visual document to fuel support or, perhaps, spark outrage over ongoing political tensions. Editor: Precisely! I see the Dutch Revolt as the print's political context. Rammekens was a strategic site, so this imagery serves as a form of political propaganda, doesn’t it? A tool used to sway public sentiment by visualizing a specific interpretation of a pivotal historical event, one that highlights military victory or perhaps mourns strategic losses. The image isn't just representing an event; it's participating in the shaping of history itself. Curator: Indeed. And observe the visual language employed. There are ships, soldiers and cannons blasting away—a complex interplay of the technology available, combined with the individual efforts and collective movements of men on the ground. How might Hogenberg, who was primarily a map maker and printmaker, thought about his craft and the way print impacted urban communities during wartime? Editor: It reminds me of other depictions of sieges and cityscapes from this period. Artists were wrestling with representing complex, three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional plane for mass consumption, contributing to collective visual literacy. So, how did prints function in civic rituals and ceremonies? It provides insight into the way communities memorialized crucial events. Curator: This examination underscores the relationship between printmaking technology, materials and the burgeoning concept of public information in early modern Europe. Editor: A perfect way to remember that images, then and now, are always engaged in complex cultural work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.