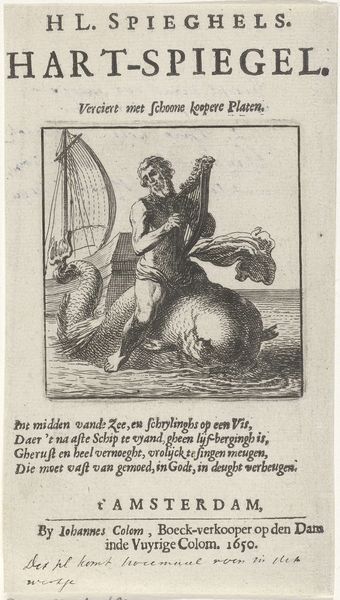

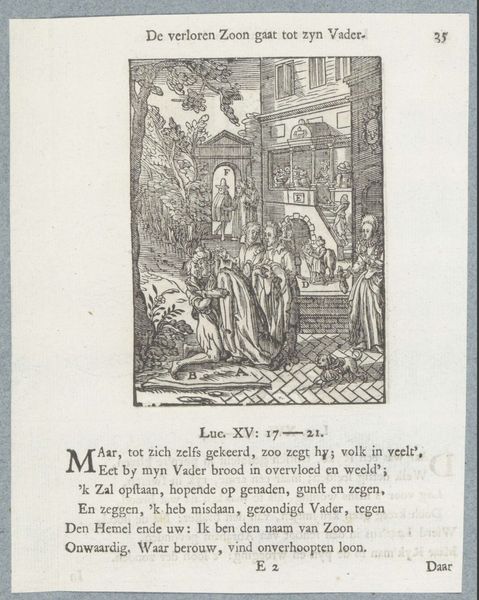

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 55 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This stark image, titled *Medea*, comes to us from Stefano della Bella, dating to sometime between 1620 and 1664. We are fortunate to have this print here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The scene is chilling. My eye immediately falls upon the dead child. The linear style and sparse composition only intensify the tragedy unfolding here. There is an almost frantic energy in the fleeing figures, with those flowing Baroque lines. Curator: Indeed. The artist uses an engraving technique to tell this very brutal tale, a tale that has captivated artists and audiences for centuries. It is also clear, if we examine the writing on the sheet, that the print also tells its tale verbally in script. Editor: The story of Medea, as I recall, is not one of subtle grace, or the power of divine order. More so, I am always reminded of its chaos. This rendering, from what I can read here, focuses on the raw violence of the myth. We see not only the act, the bodies there, but feel the emotional storm within her. This resonates with historical parallels and sociopolitical readings we can infer and discuss centuries later. It reminds one of "tigress mothers", in that context, in ways both discomforting and poignant. Curator: Precisely, her story as a scorned woman avenging betrayal. But if we look closely at the inscription, it really drives home how Medea, daughter of the King of Colchis, uses her enchantments to help Jason acquire the Golden Fleece. Editor: I do want to interrupt to acknowledge the caption on the top corner of this engraving—Cruelle. This, like the children's bodies, helps cast a perspective to help direct its readers, as if to leave a reminder against moral corruption within courtly intrigues of its own Baroque Era. The bodies of children mark both sacrifice and consequences. It does however point toward some early concepts about how society understood infanticide, in its time. Curator: I see that this reading certainly lends another layer of depth to della Bella's work. It reminds us how artistic interpretations of this myth—and of female power more broadly—were framed through varying societal lenses, then and now. Editor: Agreed. Viewing it again, I find how the print prompts critical dialogues around societal structures, violence, power, and gender. Curator: Exactly. This revisiting allows us to reflect again upon narrative and how art shapes enduring historical and cultural themes that confront us, even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.