painting

#

painting

#

landscape

#

oil painting

Copyright: Public domain

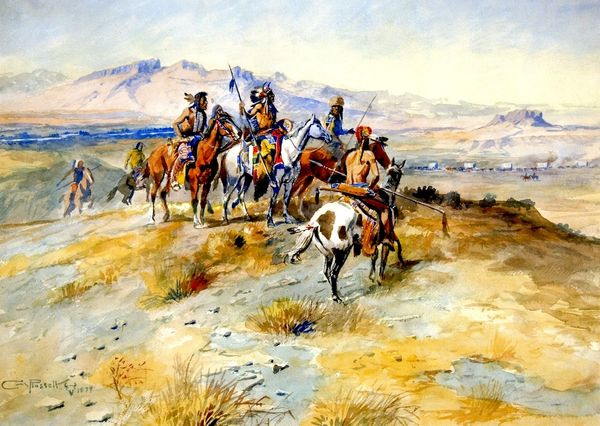

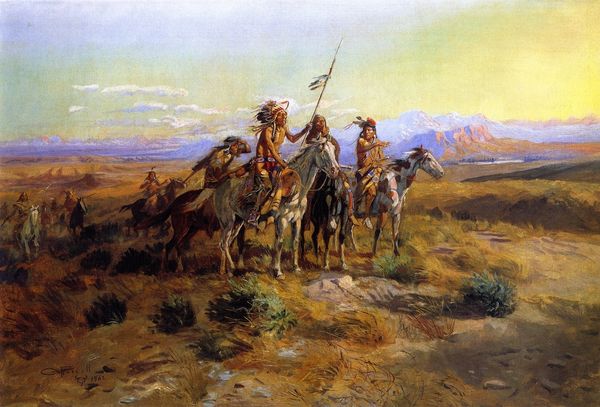

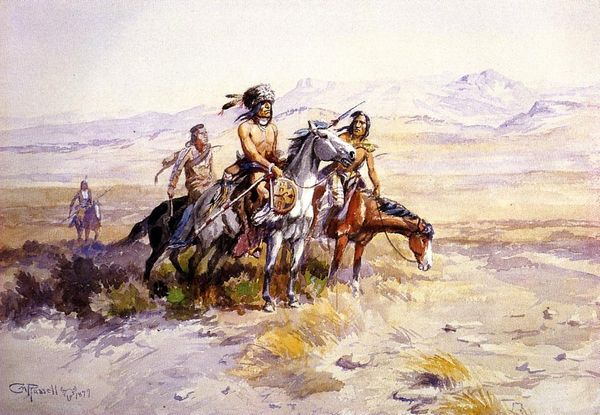

Editor: We’re looking at “Indians Scouting a Wagon Train” by Charles M. Russell, painted in 1902. It’s a watercolor depicting a group of Indigenous scouts observing settlers. The landscape feels vast and somehow foreboding. What catches your eye when you look at this work? Curator: What immediately strikes me is the romanticization of the "Wild West," a narrative Russell contributed to significantly. This wasn’t objective reporting; it was crafting a specific image, popular then and, arguably, still resonant today. Look closely: who gets the power in this image? Editor: Well, at first glance, the Native Americans do – they're elevated, literally looking down at the wagon train, surveying the scene. Curator: Precisely. But consider the historical context. This painting, made at the beginning of the 20th century, appears at a time when Indigenous populations had already experienced significant displacement and marginalization. Doesn’t that juxtaposition affect our reading of the image? It’s a history of dispossession masked as heroic observation. Editor: I hadn't really thought of it that way. So, it's not just about what is depicted, but *when* and *why* it was depicted. What purpose it serves at a very crucial moment? Curator: Exactly! Russell benefited greatly from the market eager to consume stories, even fables, of the American frontier. Also, consider how frequently museums and popular imagery reinforced similar portrayals of Indigenous peoples. How does that impact our understanding of these representations? Editor: It definitely makes you think about the responsibility artists have when depicting marginalized communities. This conversation really shifted my perspective on how art shapes our understanding of history. Curator: And hopefully encourages a more critical engagement with all imagery, particularly in how it participates in larger narratives of power and culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.