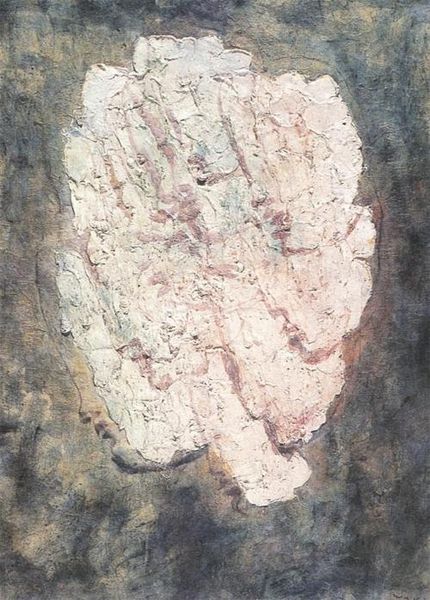

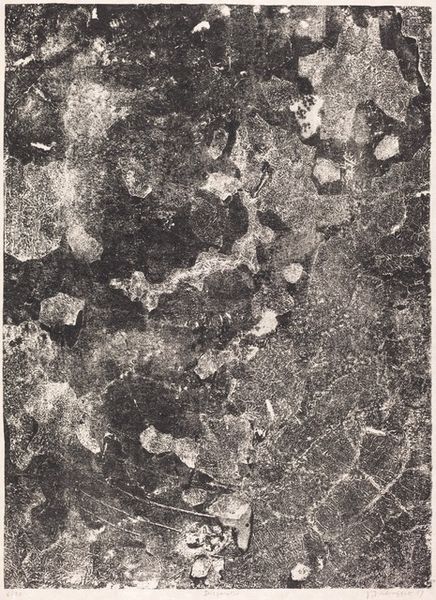

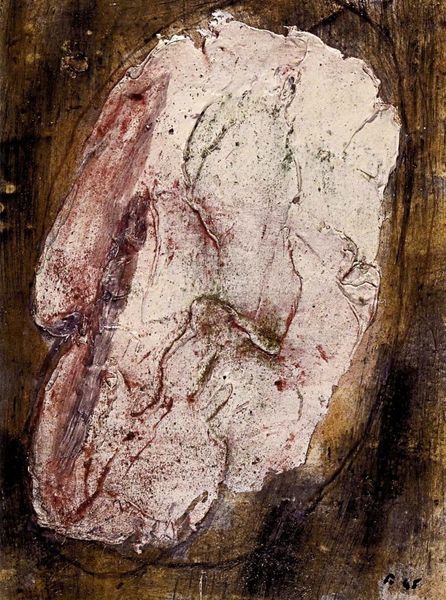

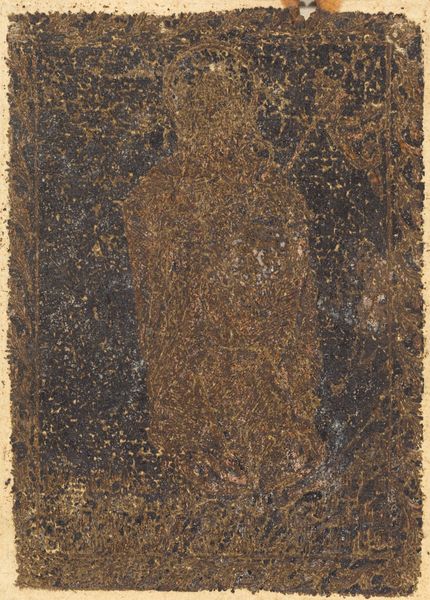

oil-paint, impasto

#

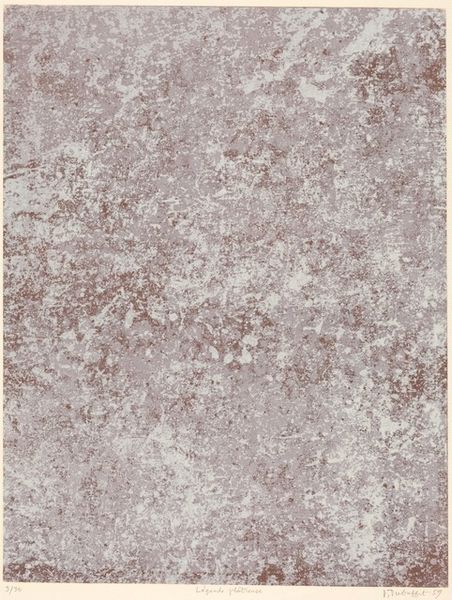

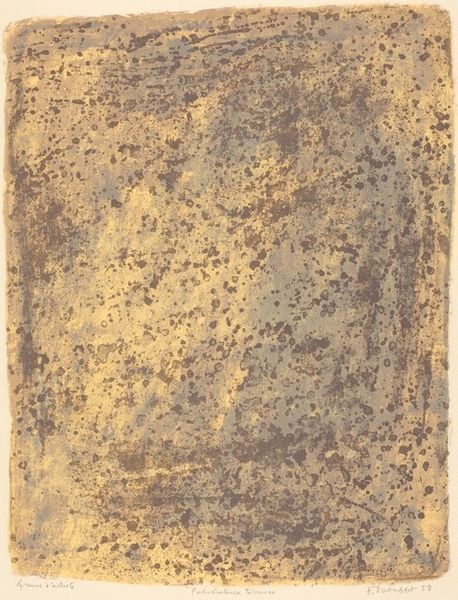

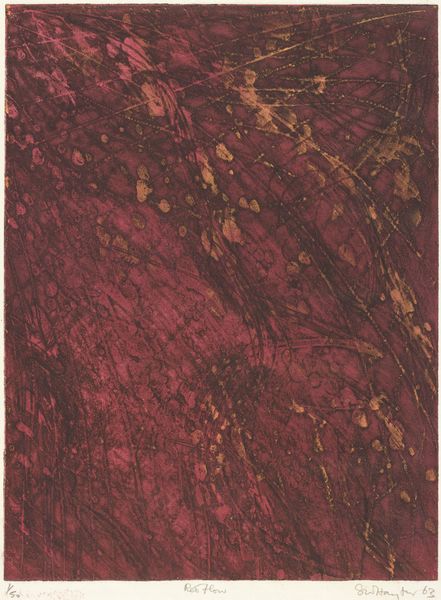

abstract-expressionism

#

abstract expressionism

#

oil-paint

#

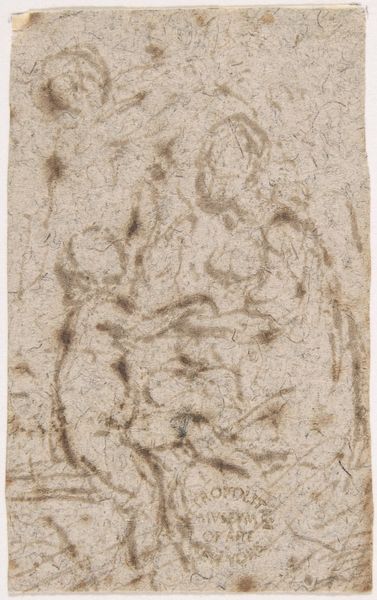

figuration

#

impasto

#

paint stroke

#

matter-painting

#

nude

Dimensions: overall: 100.9 x 73.5 cm (39 3/4 x 28 15/16 in.) framed: 128.9 x 101.6 x 8.9 cm (50 3/4 x 40 x 3 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Here we have Jean Dubuffet’s, "Corps de dame jaspé (Marbleized Body of a Lady)" from 1950, rendered in oil paint, featuring thick impasto. It’s an imposing nude figure. What strikes me is its monumentality combined with a kind of raw vulnerability. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, immediately I'm drawn to the social commentary inherent in Dubuffet's depiction. Considering the context of post-war Europe, with its existential anxieties and rejection of traditional values, Dubuffet seems to be actively challenging conventional beauty standards, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: I can see that. It’s definitely not your typical idealized nude. Curator: Exactly! Dubuffet is confronting us with a body that resists easy consumption. The rough texture, the almost grotesque proportions… It disrupts the male gaze, reclaiming agency for the female form. Where do you see this challenging convention in the work? Editor: It’s in the surface, I think. All that built-up paint, the kind of aggressive way it’s been applied...It feels like a deliberate act of rebellion against the smooth, polished surfaces we usually see. Curator: Precisely. And the 'marbleized' aspect invites another layer of interpretation. Marble is traditionally associated with classical sculpture, with permanence and ideal beauty. By 'marbleizing' this very non-ideal body, Dubuffet is subverting that tradition, questioning what we consider worthy of immortalization. It forces us to confront our own biases and preconceptions about the body and representation. How does that idea sit with you? Editor: It really makes me rethink the role of the artist – and art itself – in challenging societal norms, and our complicity in upholding beauty standards. Curator: Indeed. This work becomes an intersectional commentary, touching on gender, representation, and power. By engaging with these difficult dialogues, we deepen our understanding of not just art history, but ourselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.