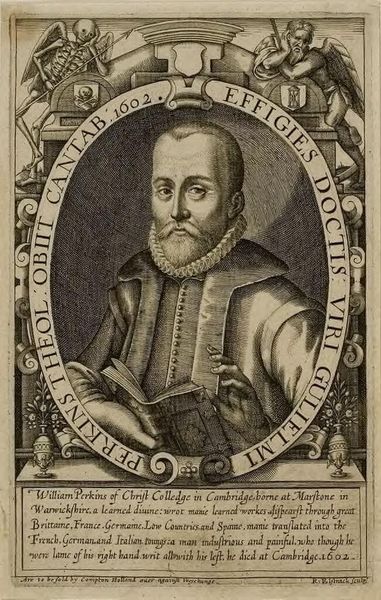

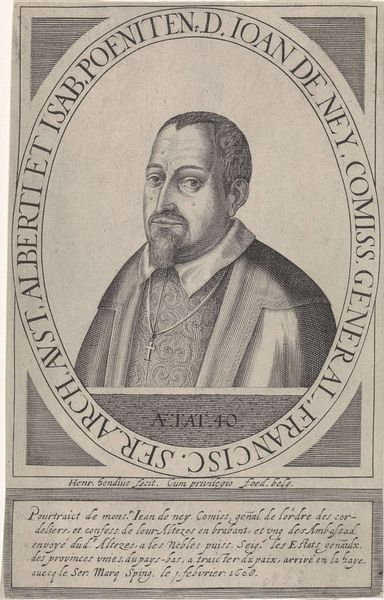

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

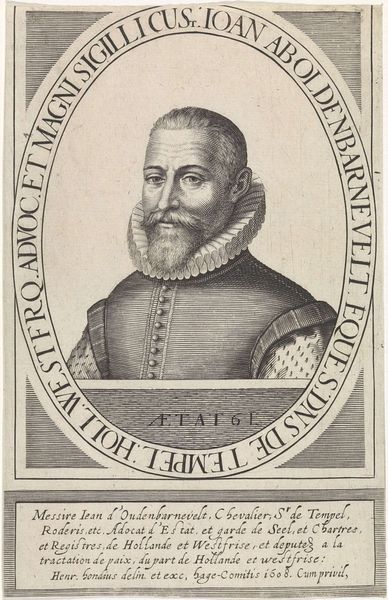

Curator: Here we have a portrait of Hippolyte de Colle, a 1608 engraving by Hendrick Hondius I, currently residing in the Rijksmuseum. It’s a striking example of baroque portraiture. Editor: My immediate impression is of the incredible precision of the engraving. The density of lines creates a very serious, almost severe mood. Curator: The severity likely reflects Hippolyte de Colle’s standing as a learned noble, councilor, judge, and curator at Heidelberg. Look at how the lettering that encircles his head within the oval declares him as such, solidifying his role. We must contextualize this image with the dynamics of power. Who had access to representation? How did printed portraiture play into broader social currents? Editor: Exactly! Consider the labor involved in creating this print, each line meticulously etched. It’s fascinating how this painstaking process, seemingly handmade, was actually designed for mass production and distribution of imagery. How do you think access impacted visual culture? Curator: In terms of visual culture and politics, portraits like these served as a powerful means to consolidate not only his position but that of his contemporaries and social circles, solidifying a highly visible elite class. Furthermore, the image emphasizes learned European ideals that stem from Humanist principles; the inscription declares Colli noble et docte (noble and learned), therefore perpetuating that identity. It speaks volumes about societal values and aspirations. Editor: Right, and thinking about Hondius himself – how did the demands and patronage system of early 17th century printmaking influence his output? It makes you wonder, what were the common practices between patron, publisher and engraver, how much material negotiation occurred between them? Curator: These collaborations influenced the transmission of knowledge and shaped visual representations across Europe. The “Cum privilegio” that concludes the inscribed block also suggests intellectual protection as it alludes to printing regulations and a nascent concern about intellectual property during the period. Editor: Considering both the technical skill and the social implications really enriches my understanding. It moves the piece from just a face to an object embedded in complex systems. Curator: Exactly! This interplay is the space where critical understandings about social representation and identities can thrive. Editor: It changes my viewing of it from a rigid and remote portrait, into a dynamic, charged artifact that is ripe for cultural and class interrogation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.