bronze, sculpture, marble

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

classical-realism

#

bronze

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

decorative-art

#

marble

#

nude

#

male-nude

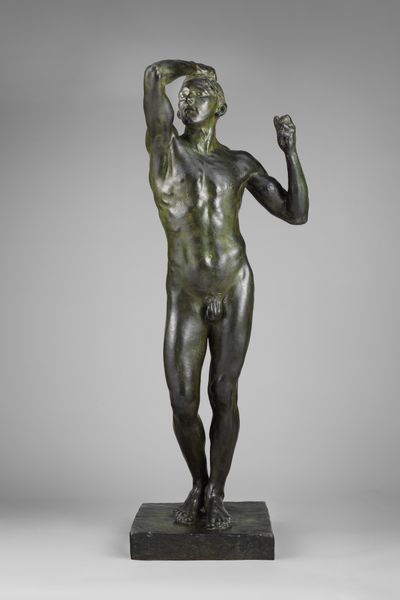

Dimensions: Height: 10 3/16 in. (25.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I'm immediately struck by the texture of the marble, or possibly bronze here, lending an almost palpable vitality to this figure. It appears to shimmer under the gallery lights. Editor: This is Adam Lenckhardt’s "Neptune," likely dating from the mid-17th century, sometime between 1630 and 1665. Here, the classical male nude is given a Baroque spin as we see the sea god actively claiming his power and domain. Curator: The raised arm is a gesture toward dominance and control, absolutely. One can really imagine the physical exertion required to sculpt this, consider the specific tools— chisels, rasps— used to meticulously remove material. Also, think of the cultural demand for classical works in this moment. Who was buying this sort of imagery? Editor: That's a pertinent question. The ruling elites, no doubt, solidifying their divine right and associating themselves with the timeless strength and dominion of classical gods. This “Neptune” emerges at a time of increased maritime and mercantile exchange and competition where colonial power was secured and asserted. He is nude but holds a dolphin representing prosperity, navigation, as well as being a symbol of sacrifice. This objectifies human and natural resources into one. Curator: And that smooth, polished surface would have taken an incredible amount of labor to achieve. Each mark painstakingly erased or blended in. How long, and with how many assistants? These questions of production and skill really intrigue me, also making me question this idea of him laying claim and of his inherent “power” if the sculpture would not exist if it weren't for countless and unknown artisans who helped. Editor: Right! The mythmaking works on so many levels. This “Neptune” embodies a tension that remains relevant to contemporary global issues of labor, resource extraction, and the enduring legacy of empire. Who is really doing the "work" becomes questionable when considering historical contexts like these. Curator: Definitely. I can appreciate how analyzing even a single work such as this brings forth such complexity in regards to labor, the power of the rulers and their visual claim to dominance. It’s so very compelling. Editor: For sure. The intersection between the story this represents and how it came into being through labour highlights the politics inherent in art production and reception, making it continually relevant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.