photography, albumen-print, architecture

#

sandstone

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

oil painting

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

islamic-art

#

albumen-print

#

architecture

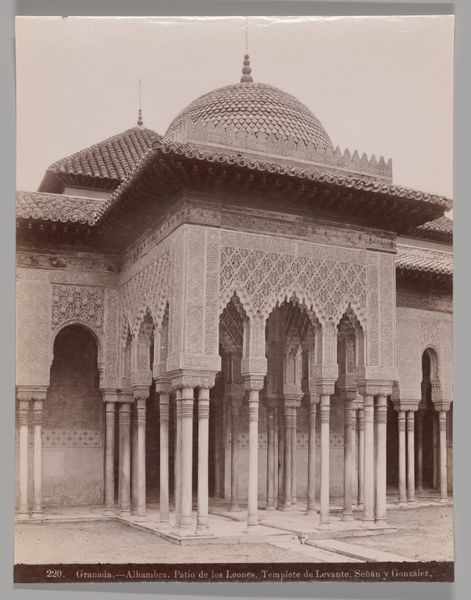

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 123 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

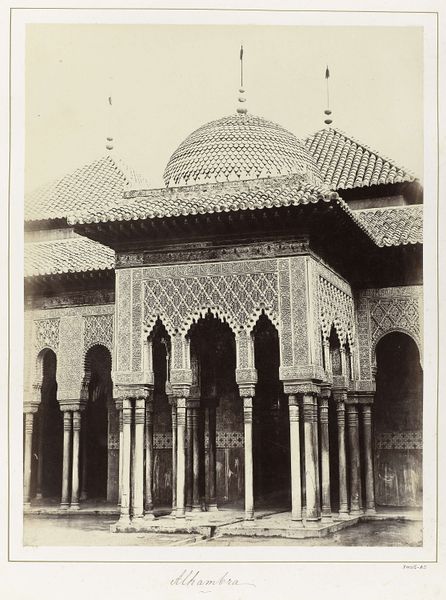

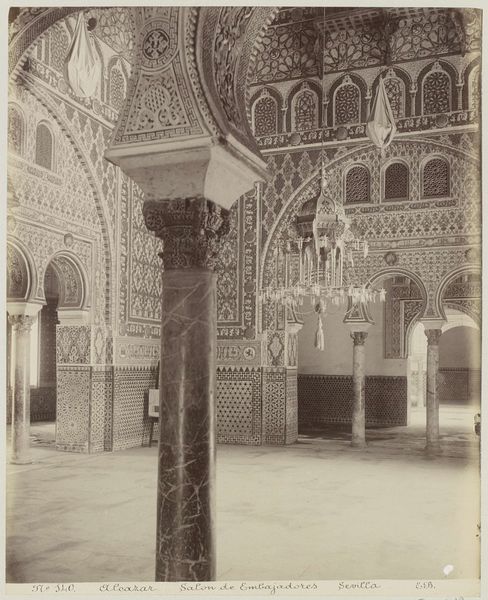

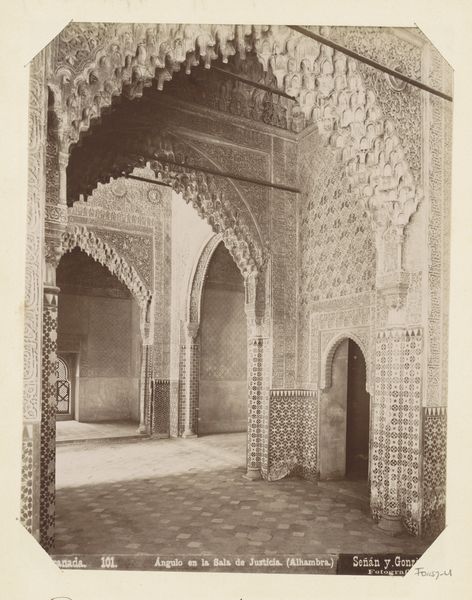

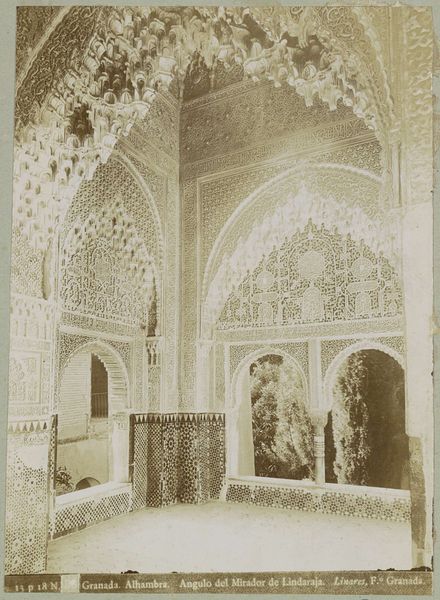

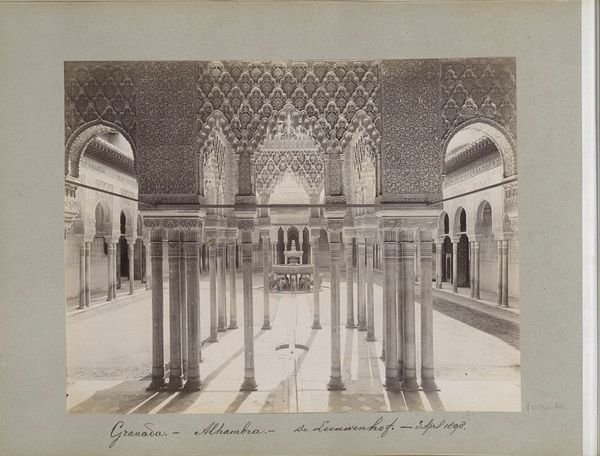

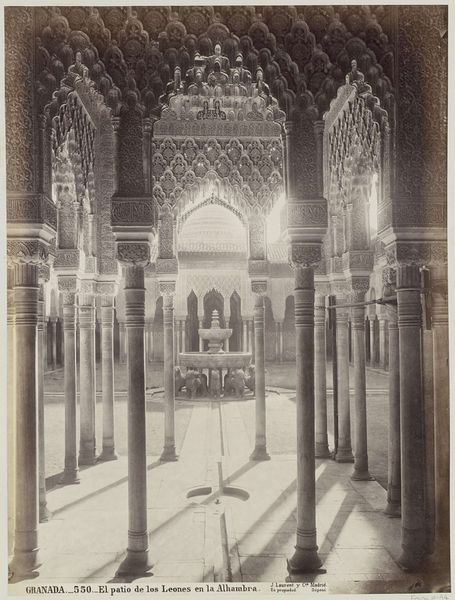

Curator: This albumen print, likely dating between 1860 and 1900, captures the Temple in the Court of the Lions at the Alhambra. It's attributed to F. Linares. Editor: It has a dreamlike, almost ethereal quality. The light and shadow play so gently across those arches and columns. It feels utterly serene. Curator: This photograph sits firmly within the tradition of Orientalism, popular at the time. It offers a Western gaze on Islamic architecture, emphasizing its exotic and picturesque qualities for European audiences. Editor: Absolutely, but I’m also struck by the repetitive nature of the columns, the geometric patterns… Look closely—the print quality makes the sandstone seem almost textile-like. What about the craft involved in the building of the structure itself, then captured by the photographer? Curator: The Alhambra, of course, holds immense historical weight. Constructed mainly in the 13th and 14th centuries, it embodies the power of the Nasrid dynasty and the sophistication of Islamic art and culture in Spain. This photograph offered viewers a tangible connection to a bygone era. Editor: Tangible, yes, but also mediated. Albumen prints were often hand-touched, manipulated, blurring the line between documentation and artistic interpretation. I’d argue the photographer had more hand in shaping the Western view than we think. Also the lack of human presence, this staged emptiness suggests the artist's intent in representing the place like an idealised picture rather than actual scene of a inhabited palce. Curator: That’s a fair point. The politics of representation are always at play. The popularity of such images reinforced certain cultural perceptions. Editor: Exactly. By examining its materiality and the means of its production we can appreciate the complexities embedded within what seems like a simple landscape shot of ornate geometric designs. Curator: So, it's both a window onto a historical place and a reflection of the society that produced it, inviting a discussion about the intersection of place and culture? Editor: Precisely. It pushes us to consider whose story we are actually seeing when we gaze upon these intricate patterns and aged sandstone.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.