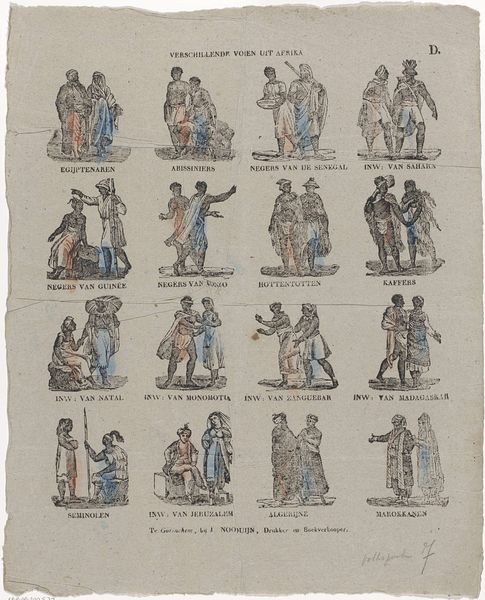

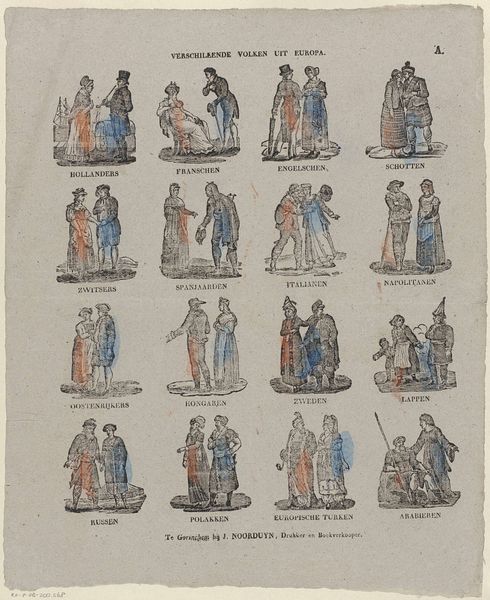

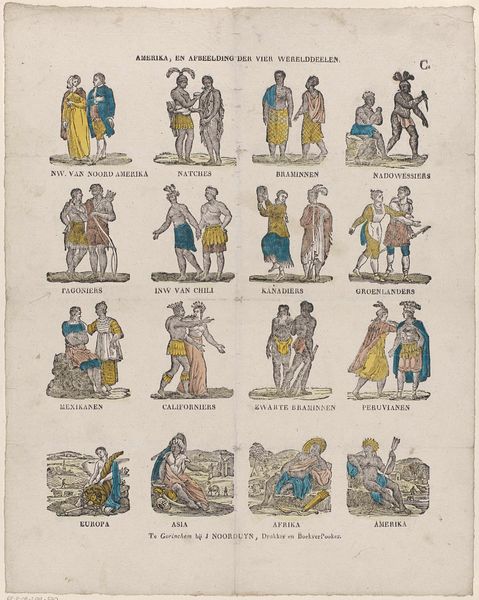

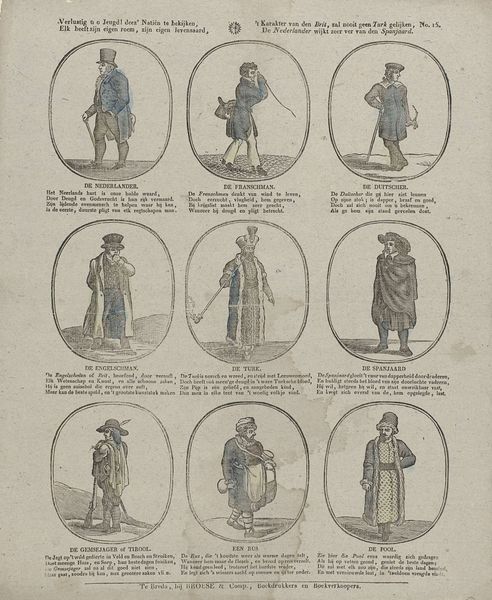

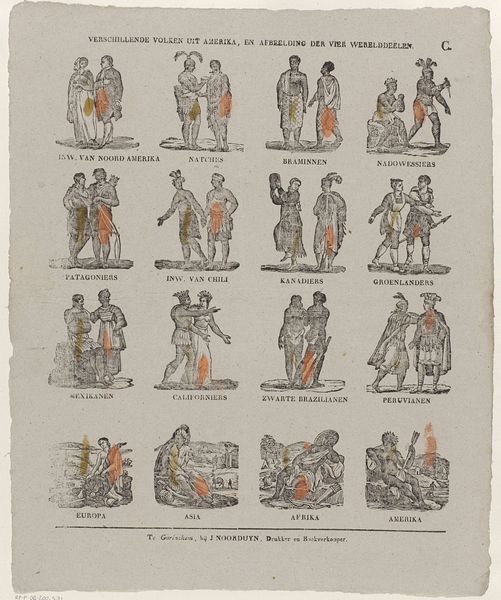

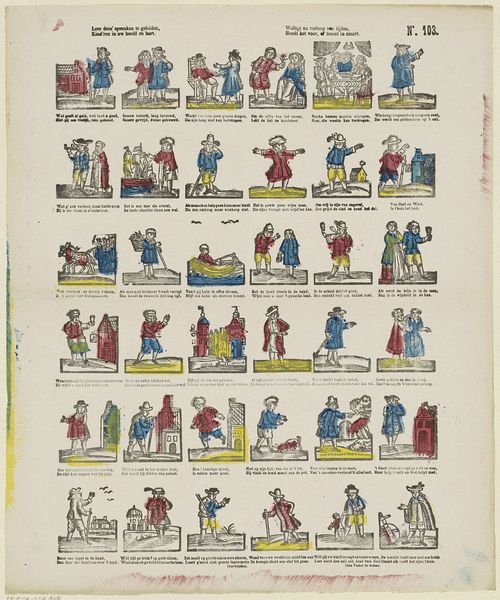

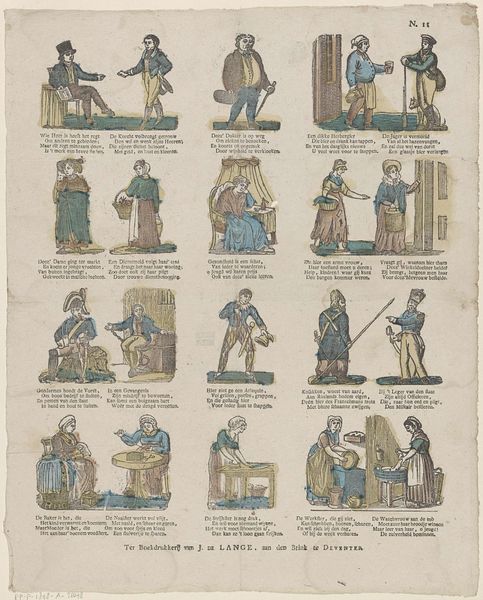

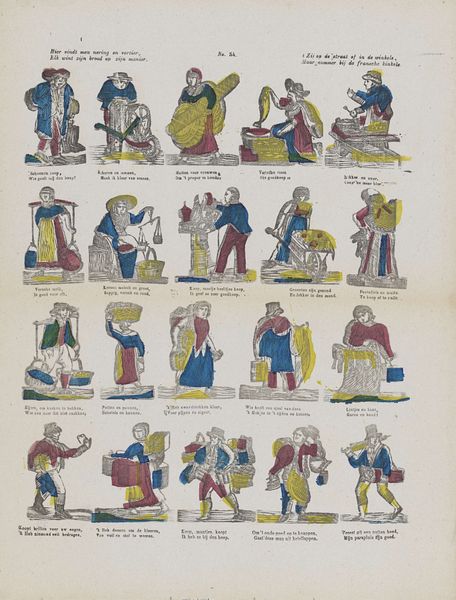

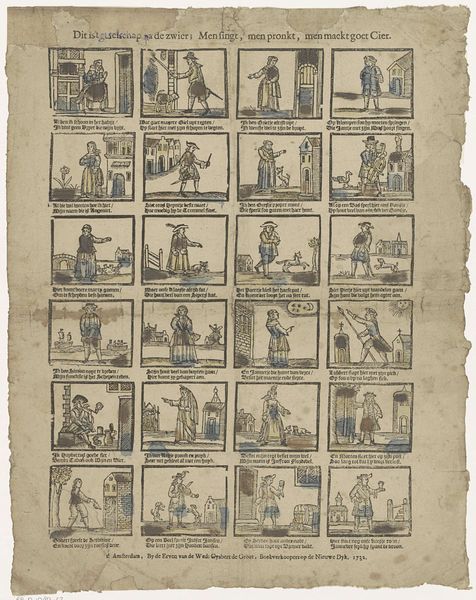

drawing, print, paper, engraving

portrait

drawing

asian-art

paper

orientalism

engraving

Dimensions: height 405 mm, width 334 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, a muted, almost melancholy air. It’s the limited color palette, perhaps, that lends this antique feel—though the subjects are teeming with implied narratives. Editor: Indeed. This is a print titled "Verschillende volken uit Azie en Australie," or "Different Peoples from Asia and Australia," dating roughly from 1819 to 1840. It's housed here at the Rijksmuseum and attributed to Alexander Cranendoncq. It depicts various ethnic groups, rendered through engraving on paper. Curator: "Different Peoples" sounds clinical, doesn't it? And "rendering" feels so cold. I sense Cranendoncq aimed to capture essences—those imagined truths of far-flung lives. But does "essence" collapse into stereotype in a project like this? Editor: That’s a key question when considering images from this period. Prints like this were often made for educational purposes, or perhaps to satisfy a public curiosity about other parts of the world, particularly through the lens of nascent Romanticism and what we now recognize as Orientalism. Curator: Ah, the double-edged sword of Romanticism! It promises empathy, even wonder, but all too often delivers caricature draped in exoticism. Look at the postures: each pair stiffly represents, embodies...what exactly? What stories are unspoken, lost in translation? Editor: The charm, I suppose, lies in that tension. These aren’t photographs attempting realism. Instead, each vignette acts as a cultural shorthand. It's up to us to unpack those assumptions. We must remember that depictions of the 'exotic' in art are intrinsically tied to the socio-political contexts in which they were made. How empires understood, and often misunderstood, their territories and the peoples who inhabited them. Curator: It feels ethically fraught now, doesn't it? Though visually captivating, one wrestles with the implications of viewing other cultures almost like specimens pinned to a board. Editor: Absolutely. Recognizing that discomfort, engaging critically with these prints, allows us to confront our own historical position. It serves as a valuable reflection on representation and power dynamics. Curator: Beautifully put. This compels us to be viewers more conscious—perhaps to unlearn as much as we learn, in looking. Editor: Precisely. A challenge, and perhaps even an invitation to deconstruct inherited ideas.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.