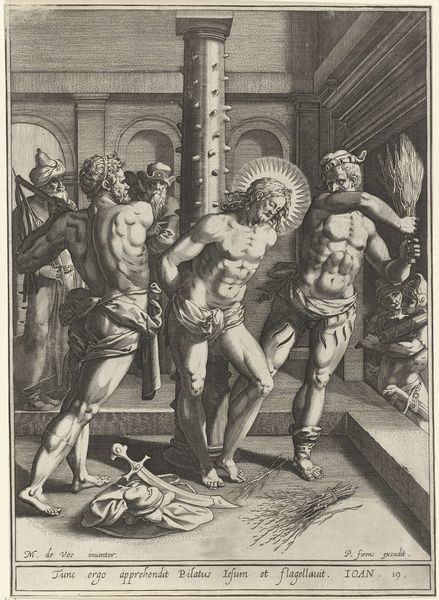

print, intaglio, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 289 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Christ Crowned with Thorns," resides here at the Rijksmuseum. It was made sometime between 1590 and 1638. What's striking to you about it? Editor: The drama jumps right out. It's Baroque, after all, designed to provoke a strong reaction. All these aggressive figures surrounding Christ, pressing that crown onto his head. Curator: Yes, the technique is quite remarkable. The use of engraving and intaglio, specifically, creates a real texture, you know? You can almost feel the roughness of the paper. And consider the labor: each line etched meticulously. Editor: And we cannot ignore the obvious social context. This scene, a pivotal point of religious and political power, resonates throughout Western history, justifying all kinds of atrocities against marginalized bodies. Christ becomes the ultimate symbol of the suffering innocent. Curator: The printing process itself—how it makes these images reproducible, consumable, to be displayed widely, taught as an acceptable narrative for oppression and religious conquest. Editor: Precisely! The consumption is critical here. Prints like this reinforced societal power structures. Who commissioned this? What were they trying to convey to its audience? Curator: Though anonymously made, the artistry involved suggests it wasn’t intended for the poorest audiences. Paper was expensive! The intaglio process requires training and tools—so likely a wealthy patron with clear political or theological intentions. Editor: Look at the composition, almost a visual attack. The crown becomes a grotesque parody of royal authority. And there’s text too! A Latin quote, underlining this theatrical humiliation. I feel a potent blend of anguish and controlled narrative, where empathy becomes a tool for manipulation. Curator: That intersection, between craft and the manipulation of emotions for religious purposes—that's really the core of its continued resonance, isn't it? It underscores our fraught history with image-making as both propaganda and devotion. Editor: It also points to the urgent need to unpack not only what this print means in a vacuum, but what its legacy has meant—how images like these shape contemporary conversations around power, race, and justice. Curator: Exactly. A reminder that art is never truly neutral. Editor: Absolutely, understanding this print’s creation and journey lets us interrogate, not just admire, its power today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.