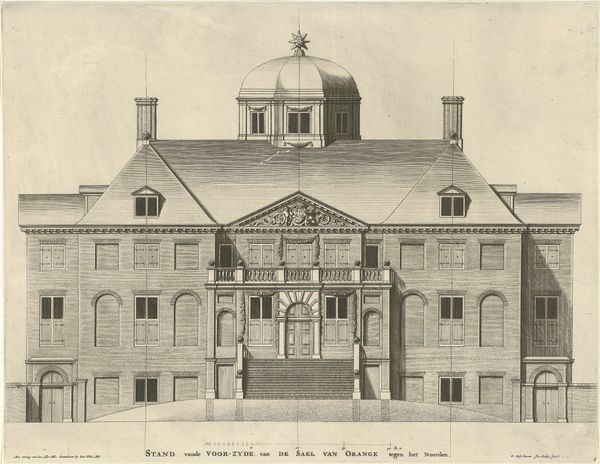

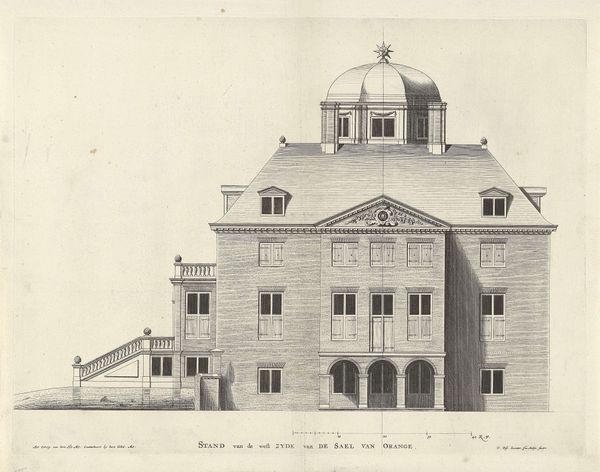

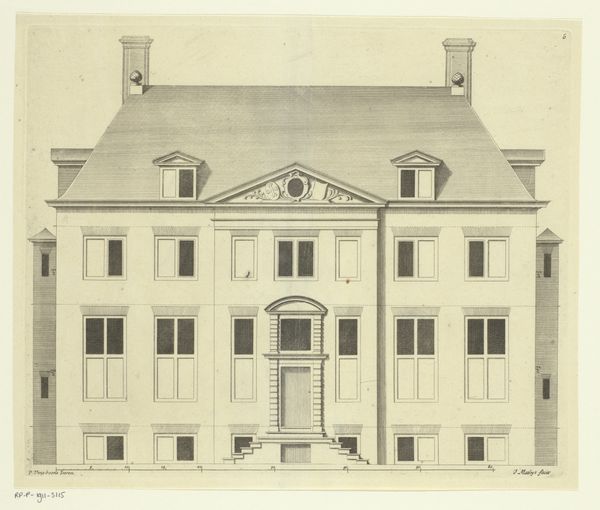

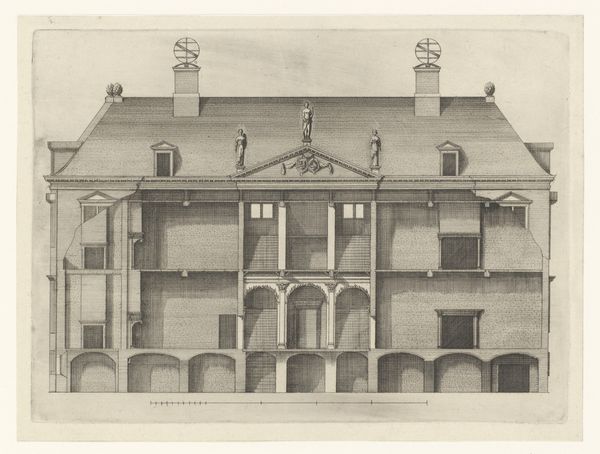

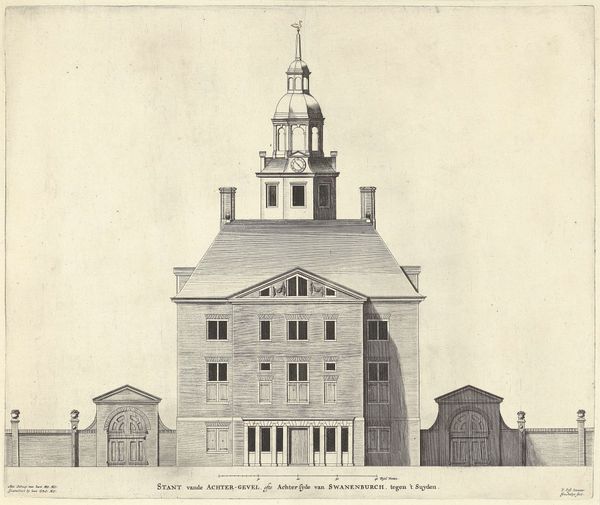

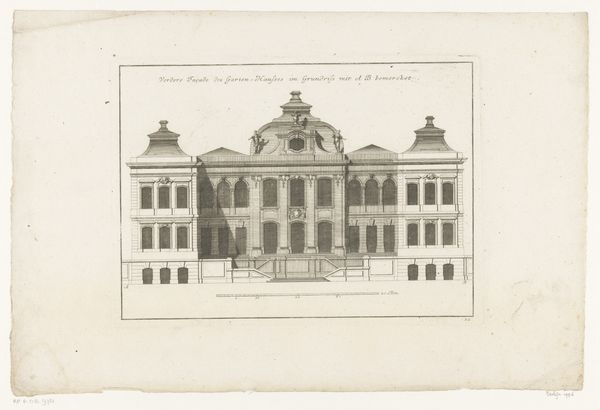

print, engraving, architecture

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

geometric

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 294 mm, width 387 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Pieter Nolpe’s “Achterzijde van Paleis Huis ten Bosch,” dating from 1655, gives us a rear view of the Palace Huis ten Bosch. It's rendered as a print, a testament to the architectural and landscape aesthetics of the Dutch Golden Age. Editor: There’s a powerful sense of order. The facade is so deliberately symmetrical, like a face staring back at you, but drained of emotion. An idealized expression. Curator: Consider the political backdrop. This wasn't merely documentation. It was carefully orchestrated imagery that spoke to the consolidation of power and nation-building after the Treaty of Münster. The very act of commissioning such a print broadcasts a statement. Who is the image for? Who is seeing, or supposed to see, the might behind the house? Editor: And it works on several levels. The engraving emphasizes vertical lines, which rise to this central dome crowned with a radiant emblem. Symbolically, a celestial object overseeing and blessing this royal structure? Is this image about divine right? Curator: Perhaps, though such symbols were cleverly employed to align with contemporary power structures, negotiating civic and divine authorities. Let’s unpack the symmetry of the architecture and what it says about power and control at the time… Editor: Before we go there...the landscape! We're presented with almost a stage backdrop. Is that because there's no lived, breathing engagement? Where are the citizens, the signs of daily life that make a home actually feel inhabited and human? Curator: Exactly! The lack of immediate human presence—while aesthetically driven—accentuates a kind of curated removal from society, a separation enacted architecturally. Even the materials used to produce and disseminate the image… the print served as a tangible marker of access to and belonging within the upper echelons of Dutch society. Editor: All these architectural details—the exactitude, precision of line—they speak of something timeless and grand. Even in grayscale, they hint at vibrant narratives—ones intentionally frozen. We need to think about which histories and voices remain unspoken in order for images of that type to endure through time. Curator: The dialogue continues. In understanding images, and Dutch art history, it is our responsibility to address its contemporary politics. Editor: And question the enduring power these icons wield even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.