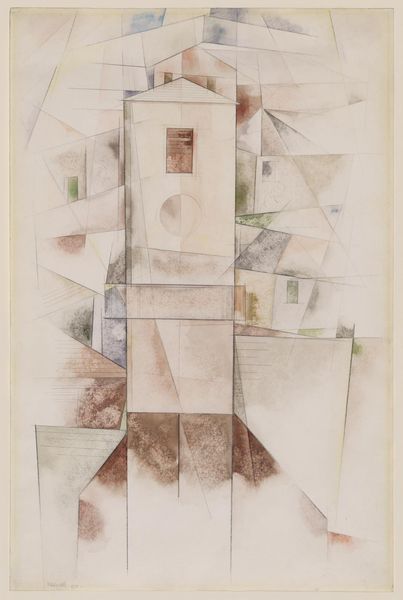

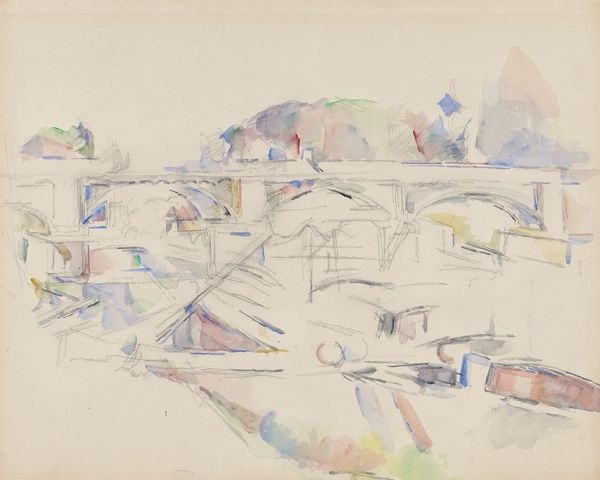

watercolor

#

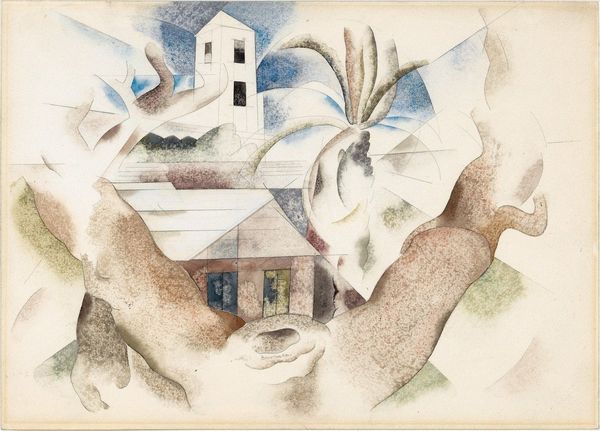

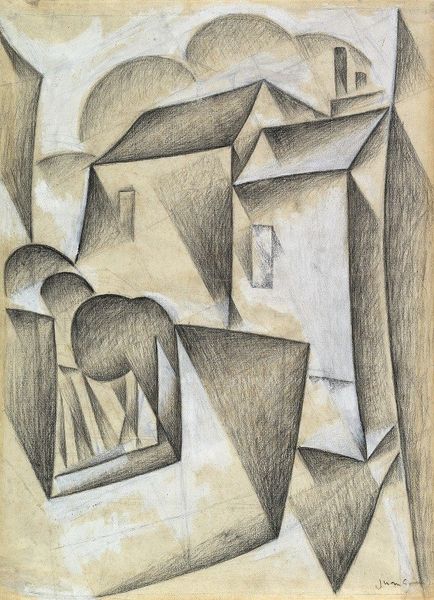

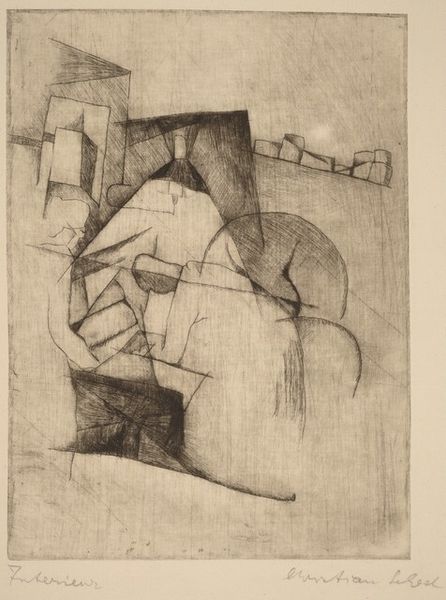

cubism

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

modernism

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

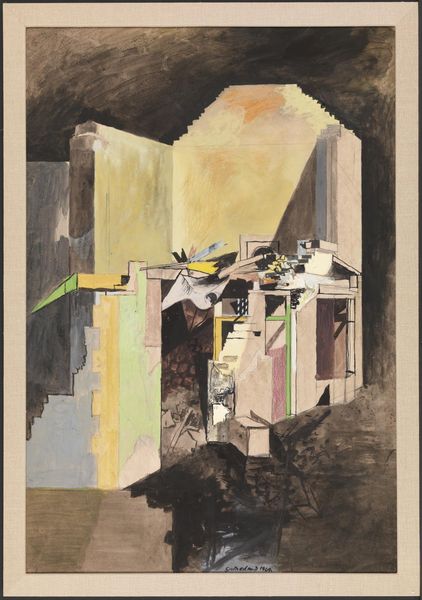

Editor: Charles Demuth's "Bermuda No. 4," created in 1917 with watercolor, strikes me as both delicate and architectural. The shapes seem to suggest buildings in a hazy landscape. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this through the lens of its materials and making. The use of watercolor itself, often associated with leisure and portability, contrasts interestingly with the geometric forms that imply a structured, almost industrialized space. Editor: So, the *choice* of watercolor challenges the traditional role it played? Curator: Precisely! Think about what was happening then. Early 20th-century art was consumed with depicting the rapid changes wrought by industrialization. But Demuth is doing this using a medium deemed less…monumental. Is he perhaps commenting on the ephemeral nature of even seemingly permanent structures? The act of rendering this scene in watercolor emphasizes its manufactured nature and impermanence, defying the solidity implied by its geometric form. The light washes even seem to question the solidity. Editor: That's fascinating. I hadn’t considered the social context of using watercolor. The very choice of the material impacts our understanding of the *built* environment within it. Curator: The limited palette also points towards the industrial constraints of available pigments and dyes. The pastel colors feel somewhat restrained. Editor: So it's almost as if he's using these materials to reflect, not just the look, but also the means of creating this new world? Curator: Exactly. It's a portrait of Bermuda through the means of its creation— pigments, water, paper. Each element carries a weight. Editor: I see it now; it is really remarkable how a closer examination of materials brings so many layers to the surface. Curator: Indeed, by exploring the material realities and the modes of production of the artwork, we discover not only what the artwork *is* but also its profound connection to the era in which it was made.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.