drawing, print, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

modernism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

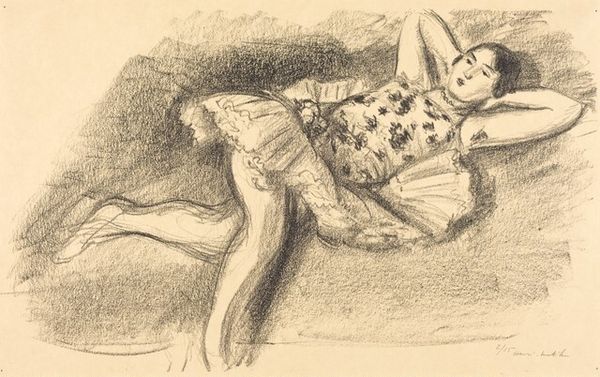

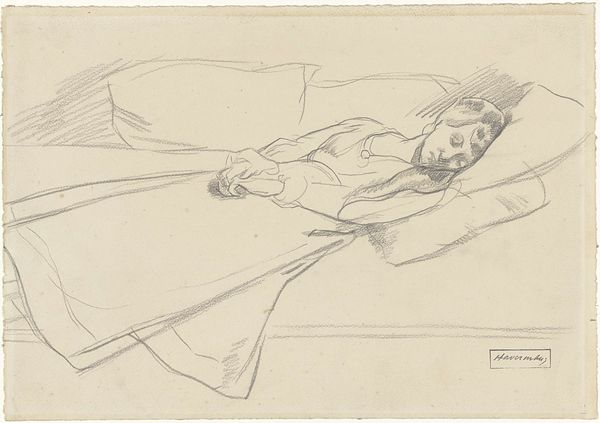

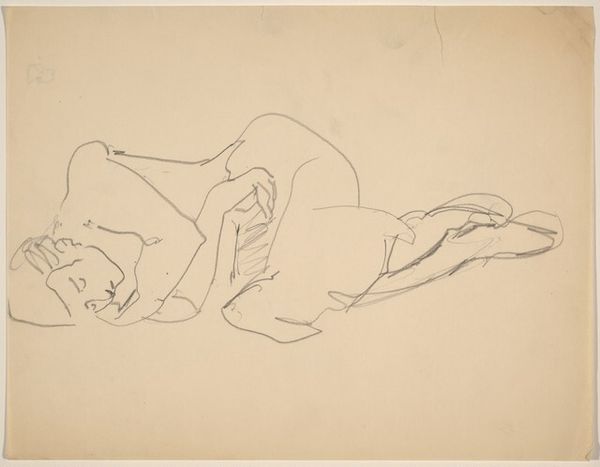

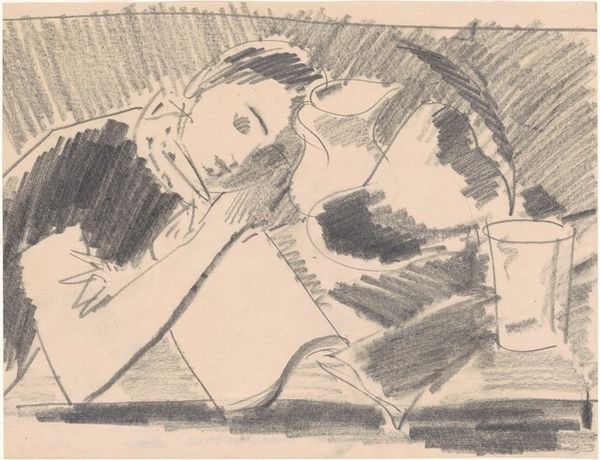

Editor: Here we have Henri Matisse's "Dix Danseuses X," created between 1925 and 1926. It's a pencil drawing or print of a dancer reclining, seemingly at rest. There is a quiet intimacy to the piece, and I'm struck by the use of line and shadow to define the form. What catches your eye about this work? Curator: My immediate reaction concerns the formal relationships at play. Note the strategic deployment of hatching. The marks that indicate shadow don’t just delineate form; they establish a rhythmic pattern across the surface of the drawing. We see line not just describing edges, but composing volumes. Consider the way the tutu is suggested: not fully rendered, but articulated through the barest minimum of strokes, implying both volume and texture through this careful reduction. Do you perceive that interplay between line and volume? Editor: Yes, now that you mention it, the almost unfinished quality adds to the feeling of intimacy. It feels like a glimpse into a private moment, rather than a finished, polished statement. Are there other areas where this tension between line and form are evident? Curator: Precisely. Consider the face: the eyes closed, suggested with just two brief strokes, yet conveying a complete sense of peaceful repose. And how the overall composition works to counter any potential reading of sentimentality: The body is positioned diagonally, activating the entire picture plane and creating a dynamic visual tension. It's a fascinating dialogue between form and line, isn’t it? Editor: Absolutely. I initially saw it as a simple drawing, but your formalist reading has shown me how much is communicated through such carefully considered choices. I never noticed that dialogue. Thanks for that. Curator: My pleasure. It's often through focused attention on these intrinsic elements that we uncover the true depth and complexity of a work of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.