relief, ceramic, sculpture

#

portrait

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

relief

#

ceramic

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

decorative-art

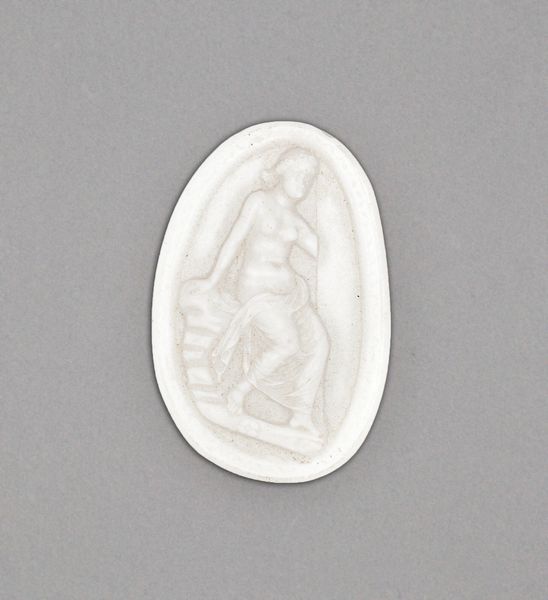

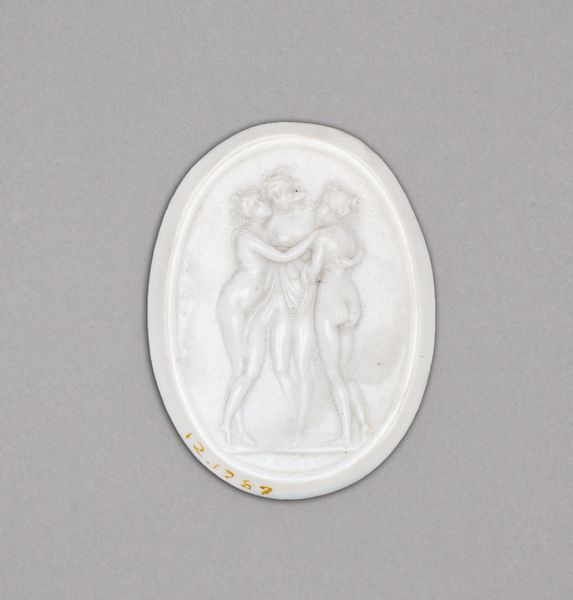

Dimensions: 5.2 × 3.2 × 0.5 cm (2 1/16 × 1 1/4 × 3/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is a ceramic relief medallion created by the Wedgwood Manufactory in the early 19th century. It calls to mind ancient Greek and Roman art with its neo-classical motifs. Editor: It strikes me as incredibly austere and cool—almost clinical with its pure white color. The shallow relief lends a sense of quiet detachment, but the scene on the left does introduce a dynamic feel. Curator: Precisely. We see a figure, likely a charioteer, actively engaged with powerful horses pulling a chariot. A narrative moment frozen in ceramic. On the right is a bust, probably depicting a goddess crowned with foliage and symbolic stars on her head, embodying divine serenity and poise. Editor: Right. But what are the implications here? A medallion manufactured centuries later in a style inspired by the art of the past, specifically ancient Greece and Rome? Does this tell us how ancient myths were refashioned to deliver different political meanings and cultural authority to very different demographics during the rise of colonial empires in the nineteenth century? Curator: The echo of Greek and Roman mythology connects viewers to foundational cultural narratives. Medallions like this one became fashionable status symbols, demonstrating one's erudition and cultivation of a neo-classical aesthetic. Editor: Fascinating, but it does raise the question of elitism. What meaning would that have for working class women struggling with limited employment prospects during the Industrial Revolution, who might not have enjoyed classical educations in the original Greek or Latin? Curator: Absolutely. And let’s think about function, too. Perhaps it was part of a larger decorative program or intended for personal adornment—worn close to the body, embodying cultural aspirations. The act of owning, displaying, and even wearing this object then reinforces those same social hierarchies and aspirations. Editor: Well, looking at the material of this decorative ceramic, it has me considering the wider reach and reproduction of artwork for middle- and upper-class collectors of this period, making artwork portable and, literally, wear-able, especially among Victorian society, and later distributed more widely throughout the rise of modern industrial capitalism. Curator: Indeed. Even on such a small scale, it reflects how visual symbols retain immense power, bridging time and cultural contexts. The symbols become both universal and culturally-relative. Editor: The quiet stories these silent forms still provoke remind us how artworks reflect broader societal power struggles, then as now. It provides new, but also older contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.