engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

traditional media

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 147 mm, width 94 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

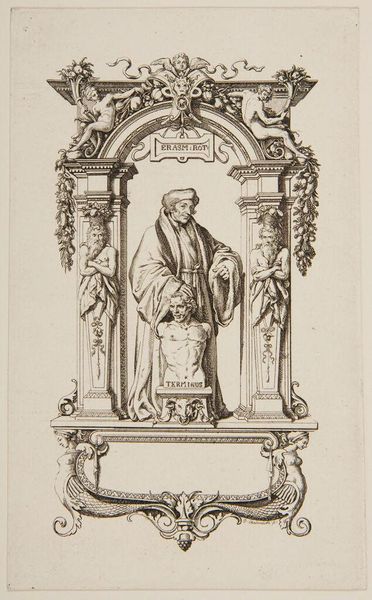

Curator: This is a rather grand engraving created in 1732 by Jan Punt. It depicts a portrait of Pope Clement XI. The work can be found here in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The texture immediately grabs you, doesn’t it? The way the light plays across the surface. Even though it’s just an engraving, the detail is phenomenal, lending a tangible depth and weight to the composition. I find myself wondering about the artist's process, and the labor involved in carving all those intricate lines. Curator: Exactly! Look closely at how Punt achieved the illusion of shadow and form using just variations in line thickness and density. He demonstrates incredible technical mastery of the engraving tools and acid-etching to convey tone and texture in this relatively mass produced medium. The availability of printmaking in the early modern world enabled the broad distribution of propaganda material. Editor: And beyond that skill, I can't help but consider how these portraits played a role in constructing and reinforcing religious authority, it seems. I find myself dwelling on how that sort of image operated and the cultural values and assumptions it was upholding. Curator: Absolutely, it reinforced the Pope's status. Think of the baroque period in general: How the visual excess and drama served the needs of the counter-reformation. Editor: That’s a key point, that relationship between style and power! Considering, as well, who this artwork served: was this intended for popular consumption, or to cater to an elite audience, a reinforcement of power dynamics? What specific audiences were intended to find value or be impacted by this particular image? Curator: Knowing printmaking of the era, probably something in between. There was an aspirational element to Baroque art—the display of wealth was part of its meaning, and such an image, copied widely, could circulate among people in varied professions or ranks of society. The accessibility of these kinds of engravings—even compared to oil paintings, for instance—opened new markets for artists and avenues to signal allegiance. Editor: And now, as we consider these questions and details, the work moves us to reconsider what those things signify and what they communicate across time to different kinds of audiences. I appreciate the chance to think through that dynamic with this print. Curator: Indeed. Reflecting on its function in its time and its accessibility even today changes our perceptions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.