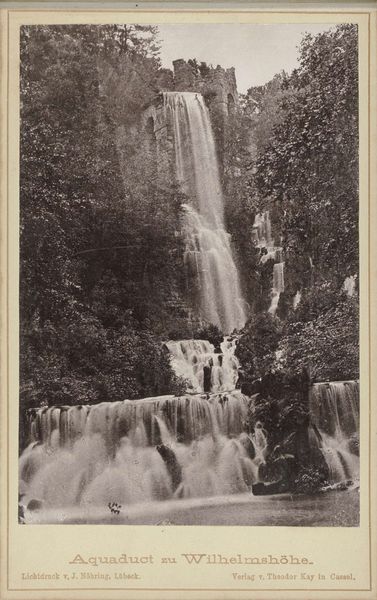

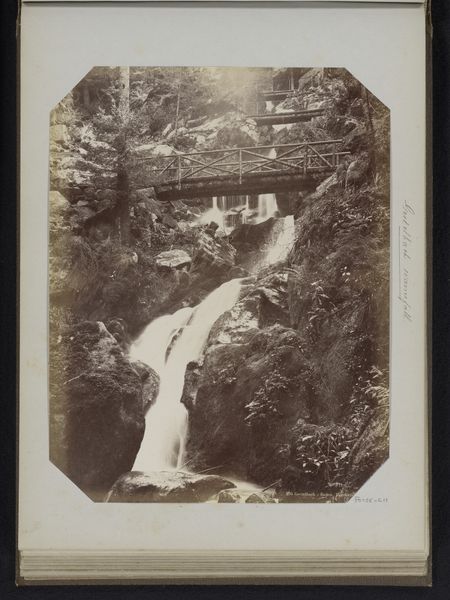

Dimensions: height 144 mm, width 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

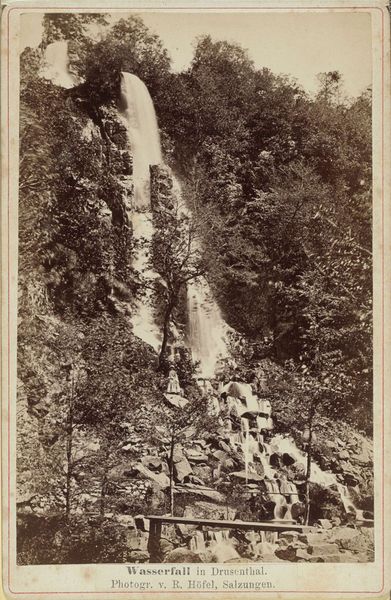

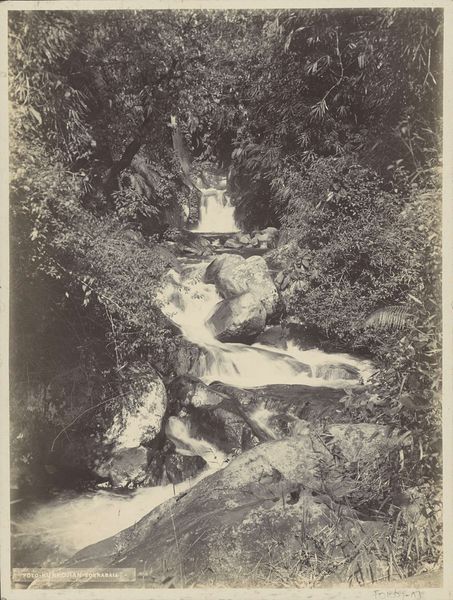

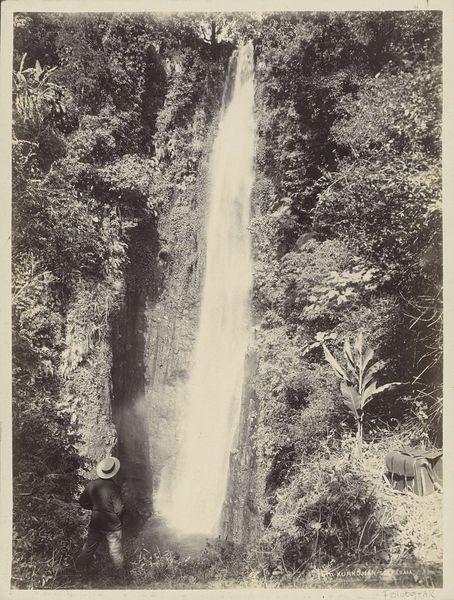

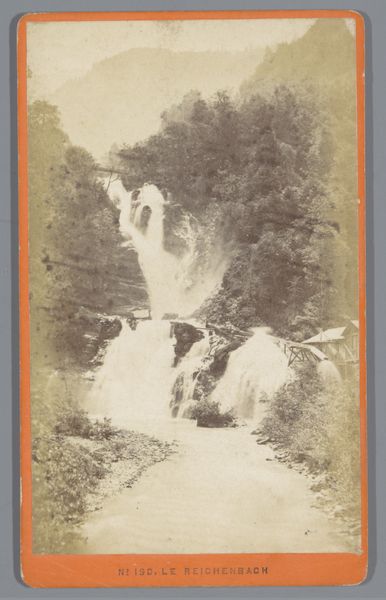

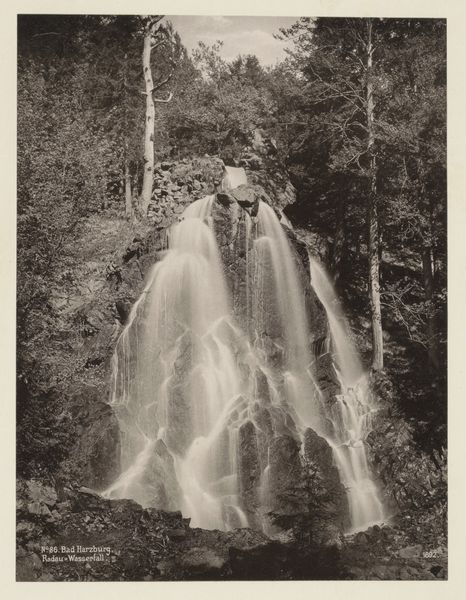

Editor: Here we have Johan Nöhring's photograph, "Nieuwe waterval in Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe," a gelatin silver print from the late 19th century. There's a real sense of Romanticism here, with nature presented as this powerful, sublime force. How do you interpret this work? Curator: This photograph allows us to examine how constructed landscapes serve to reinforce certain power structures. Consider the artificiality of the waterfall itself within the Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe, and how it was engineered as a display of wealth and control over nature. It reminds me of similar grand projects undertaken during the same period, meant to inspire awe and demonstrate dominion. Who do you think benefited most from this controlled 'natural' environment? Editor: Presumably, the elite who commissioned it, as a symbol of their status. It seems different than if it were just a natural, untouched waterfall, doesn’t it? Curator: Exactly. The very act of photographing this manicured scene elevates and disseminates these ideologies. It presents an idealized vision, concealing the labor and resources required to construct and maintain this illusion. In what ways do you see this romanticized portrayal masking underlying social inequalities? Editor: The framing almost makes it seem like a purely natural wonder, obscuring the deliberate human intervention and, as you said, the social realities of its creation. I hadn’t really thought about it that way. Curator: Think about whose stories are told and whose are omitted when viewing images like this. This forces us to reckon with art history's complicity in perpetuating certain narratives. I appreciate you sharing your reflections with me today. Editor: This conversation reframed my understanding entirely. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.