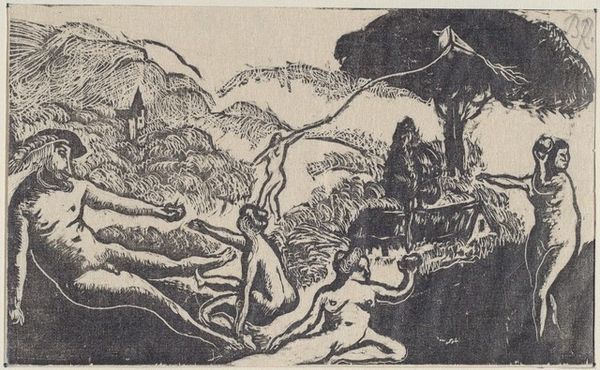

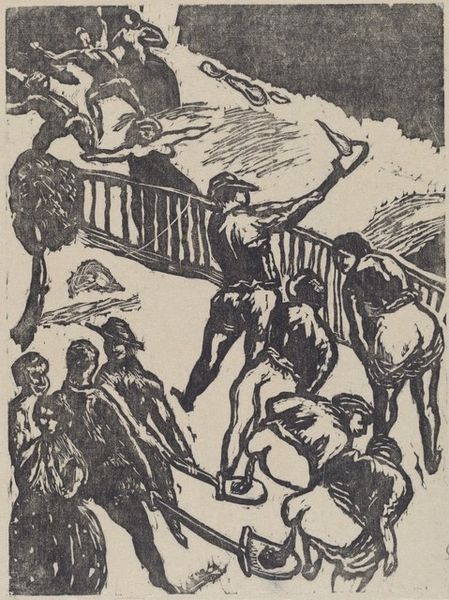

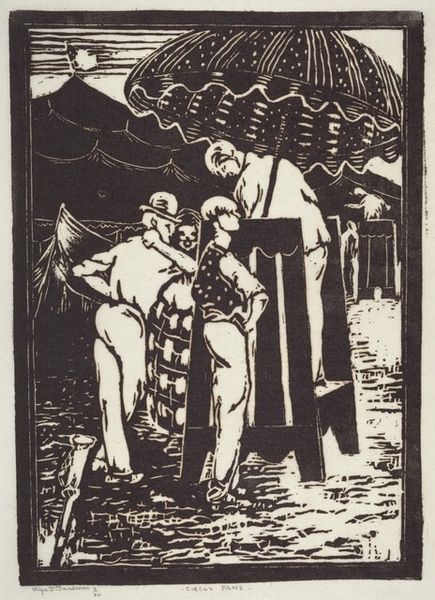

graphic-art, print, woodcut

#

graphic-art

#

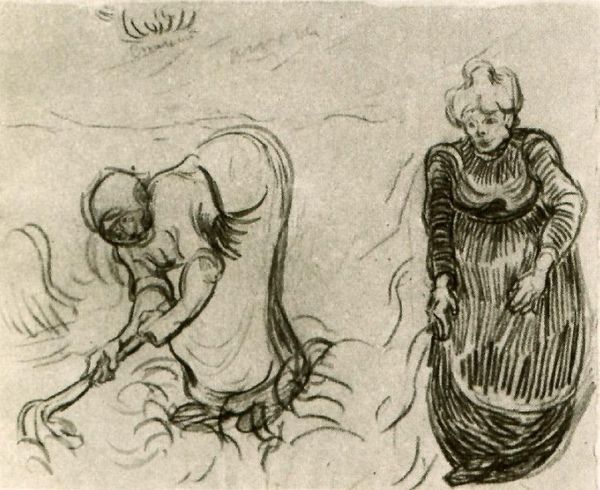

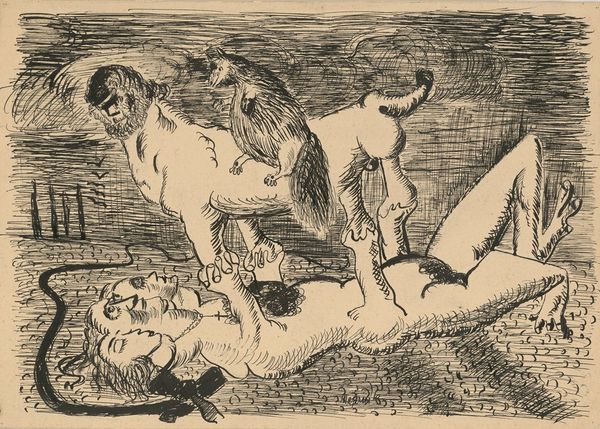

ink drawing

#

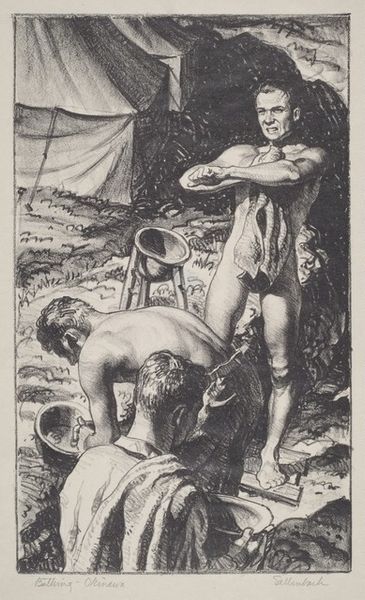

narrative-art

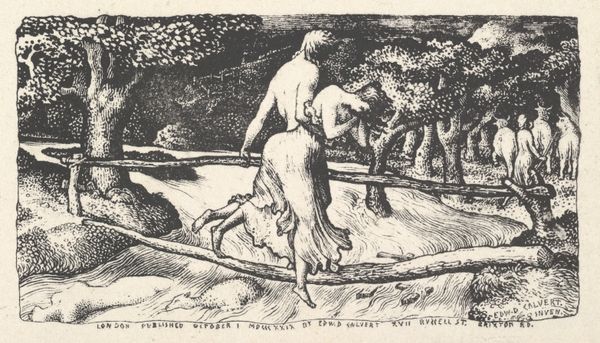

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

woodcut

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

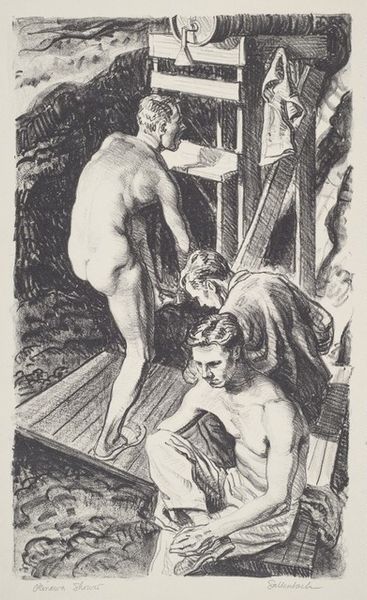

Curator: Right, so here we have "Gargantua: Chapter XXII - "Les balancoirs"," a woodcut print made by Bernard Reder in 1942. What do you make of it? Editor: Immediately, there's this sense of a strange revelry... it’s almost feverish, a very physical intensity emphasized by the starkness of the woodcut. And what scale are we talking here? It feels intimate, personal. Curator: Yes, the print gives it a unique rawness and it being a small woodcut underscores that handmade quality, defying the precision often prized in more refined printmaking techniques. The labor is evident, isn't it? Reder seems more interested in capturing a vital, immediate energy than a polished finish. Editor: Absolutely. Those deep blacks are like an embrace. I notice the landscape details and human figures are almost aggressively carved out. This reminds me of a communal labor, where each figure contributes in their own unique way to complete the community. Curator: Yes, I agree! Those stark contrasts really grab you, don't they? He's got these figures on swings and this grotesque figure looming in the foreground—a fascinating choice! Are we meant to feel a kind of anxiety or judgment or an invitation, really? The story could be ours. It seems less about showing and more about evoking…the sheer pleasure, even ecstasy, of unbridled physicality. Editor: Given its 1942 production date, amidst war, there's almost a transgressive element to its unabashed sensuality. Was Reder seeking liberation through the body by looking at Gargantua? And let’s consider the material conditions; paper itself was likely a precious commodity. These limitations actually emphasize the value and meaning that he created within a culture deeply mired in materialism. Curator: That context really unlocks a lot! Maybe there’s also an act of defiance here, a scream for liberation or self-discovery? The very act of swinging—abandoning oneself to momentum—feels intensely poignant given those historical restrictions and cultural impositions. Editor: Definitely. It urges us to see beyond just form, and material to also include the social and historical narratives. Reder's art becomes not just a beautiful rendering of bodies but a tangible relic deeply intertwined with both scarcity and desire. Curator: So true. Well, I think looking at it together has reminded me that sometimes, the rawest expressions are often the most profound statements! Editor: Indeed, especially when considering art as both the object itself and as an act of making, pushing back on norms that want us only as consumers of perfect images and instead demands we remember a material process.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.