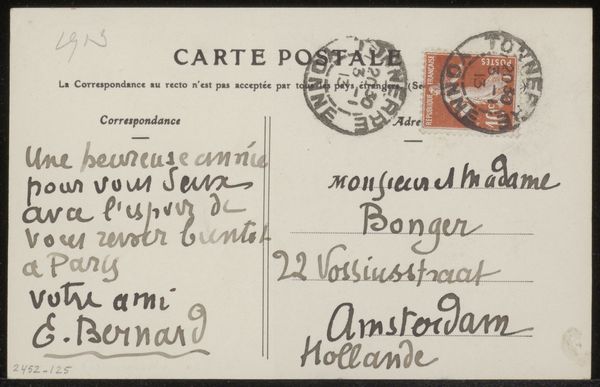

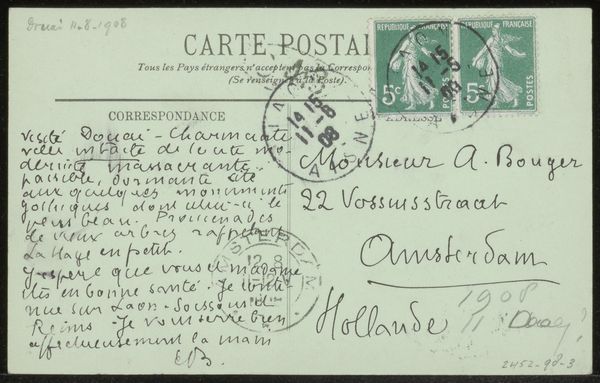

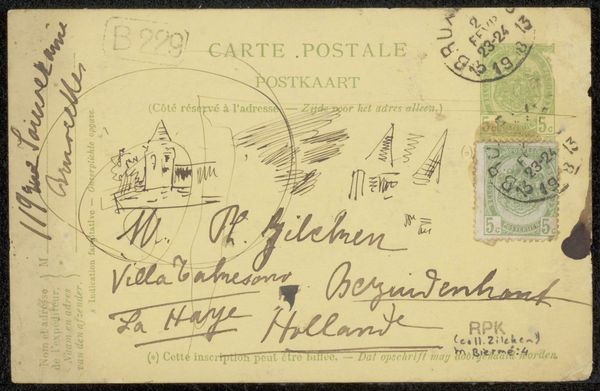

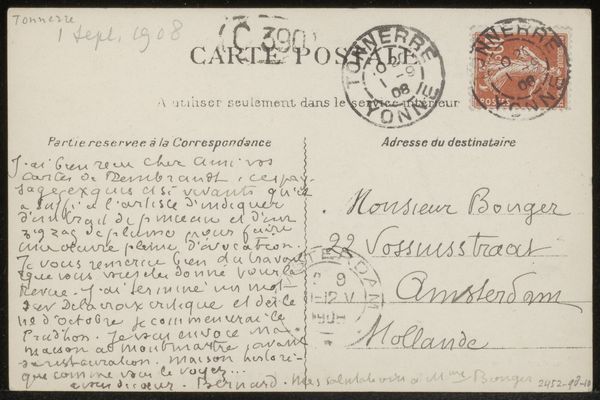

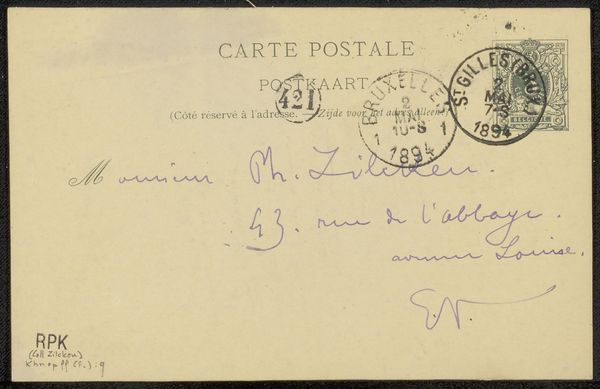

Prentbriefkaart aan Andries Bonger en Anne Marie Louise van der Linden before 1917

0:00

0:00

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

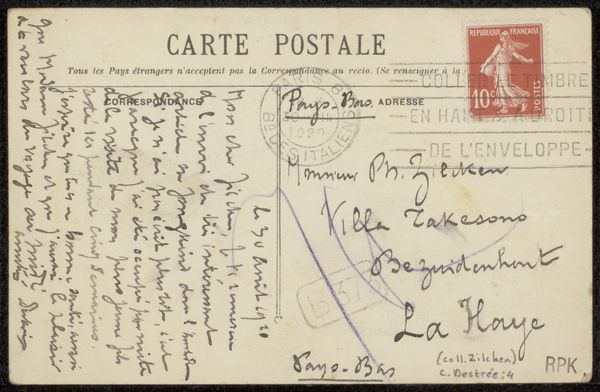

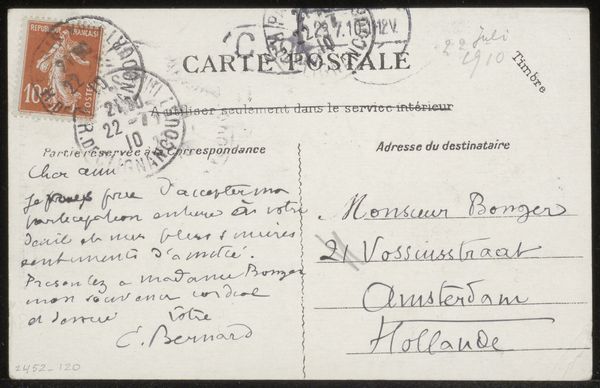

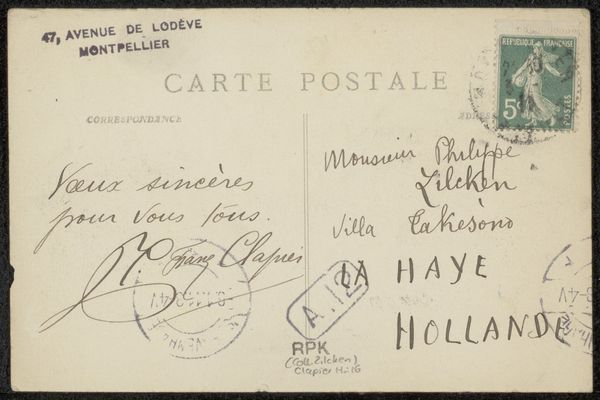

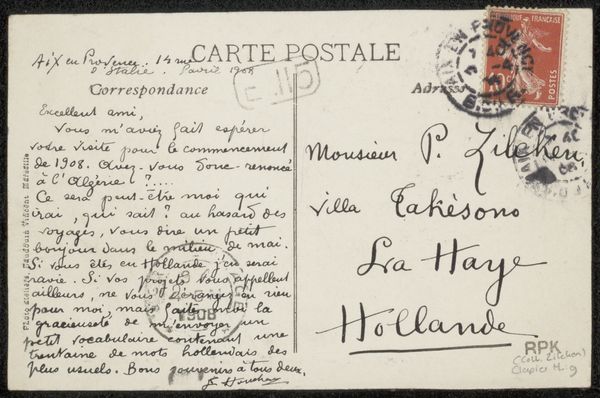

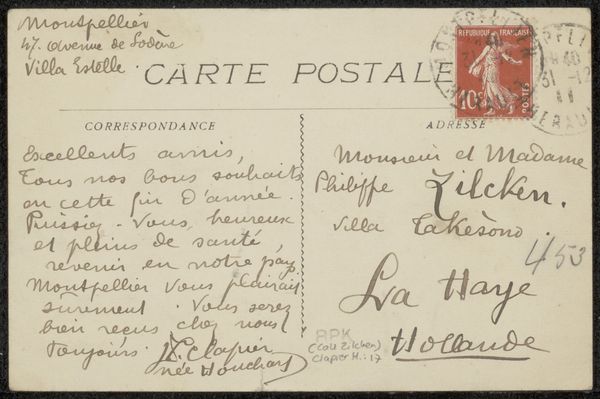

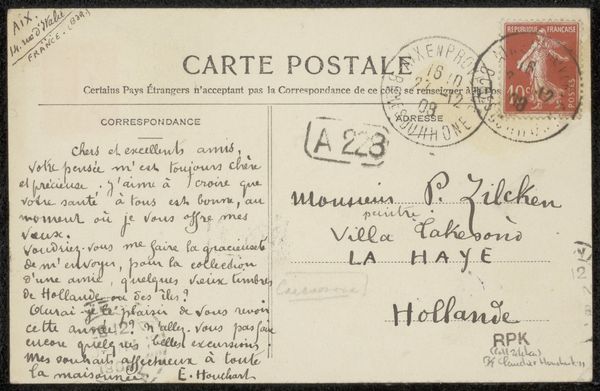

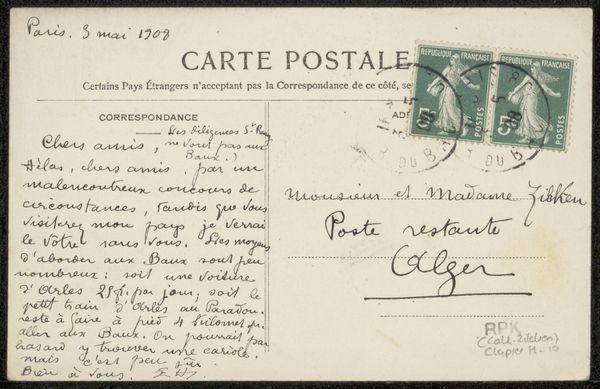

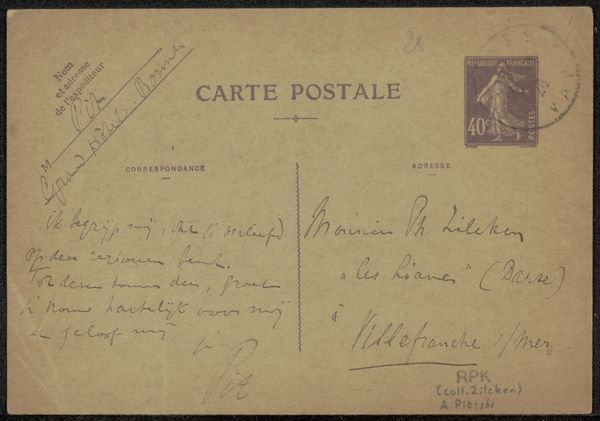

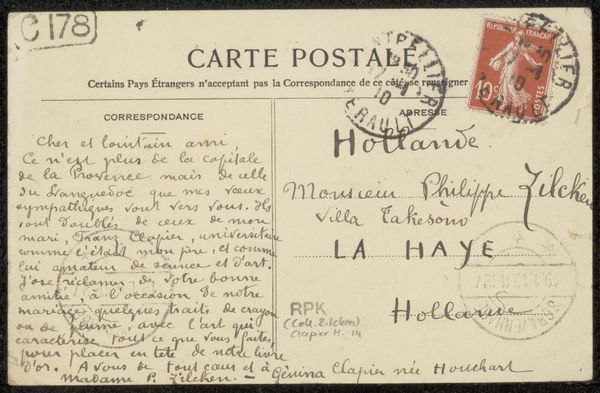

Curator: Editor: This is "Prentbriefkaart aan Andries Bonger en Anne Marie Louise van der Linden," a postcard made before 1917 by Émile Bernard. It's ink on paper, and the handwritten text is really striking. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: For me, it's about the physical exchange – the social transaction – embedded in this small object. Consider the materiality: paper, ink, the very act of writing with a pen. These are not ethereal artistic pursuits, but tangible forms of labor and communication. The postcard becomes a carrier, not just of the artist's words, but of the whole social and economic structure that enables its production and distribution. Editor: That makes sense. So you're less interested in the style—it's Post-Impressionist—and more in, like, the means of sending a message? Curator: Exactly! The calligraphy isn't just aesthetic; it represents the artist’s hand, their physical involvement. The postal stamps, the address meticulously written – these elements ground the art within a network of exchange and consumption. What about the implied reader? How do you imagine them interacting with the object? Editor: I guess the recipients, the Bongers, would've handled this and then likely kept it. They became part of this distribution, preserving a functional piece. Does that blur the line between craft and art? Curator: Precisely. By examining the materials, the labor, and the social context, we can challenge these traditional boundaries. The postcard isn’t simply a canvas for artistic expression but rather a site of production and consumption in itself. Editor: It’s interesting to think about art that way - considering not just what it depicts but its role in a much bigger system. Curator: I agree. It changes how we value the everyday "artwork," and how it facilitates societal bonds.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.