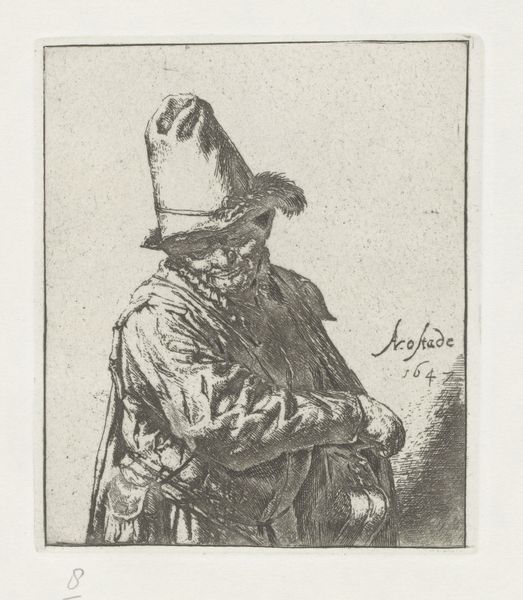

Dimensions: height 76 mm, width 45 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

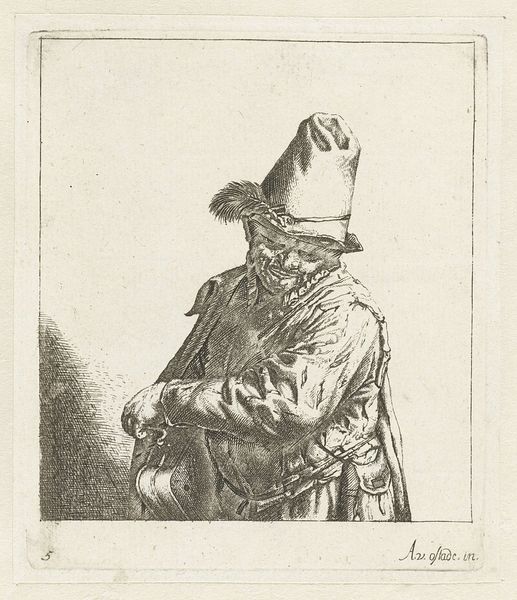

Curator: Here we have Johann Andreas Benjamin Nothnagel's "Man met tulband met pluim," an etching from 1771. Editor: There’s a certain roughness to the execution that I find captivating. It almost feels unfinished, but that adds to its directness. Curator: Exactly! This etching shows an interesting side of printmaking in the late 18th century. Look at the relatively unrefined lines; this was a quicker and likely more economical method for producing images, hinting at the democratization of portraiture during this time. Who was accessing such prints and how did that impact larger art market structures? Editor: I'm curious about that turban. Its cultural context matters here. Is it purely theatrical, an exoticized element added for artistic flair, or does it indicate something more about social perceptions or even the sitter’s profession, perhaps? What about the act of choosing such adornment at the time the etching was produced? Curator: Good question. We can certainly consider the exoticizing gaze common in Western art of that period, but let’s also focus on the process. The lines creating the turban – see how they vary in weight and direction to describe the fabric’s texture. I’m keen on seeing how the material components work to portray the idea of fabric, class and artistry all at once. The very lines of this etching show Nothnagel making intentional aesthetic decisions. Editor: The lack of elaborate detail definitely places this work into a specific sphere. This wasn’t about precise, lifelike representation like academic painting, but rather an accessible portrayal that could circulate more freely. It’s this access and visual dialogue that the artist created which gives the work value, I'd argue. Curator: Indeed. It provides insights into the broader accessibility of art and how quickly images of people—even in somewhat theatrical garb— could spread and be consumed by the burgeoning middle classes. It shows an intentional effort to meet this kind of demand in 1771. Editor: Absolutely. These pieces force us to rethink hierarchies within art history, who decides the value of different aesthetics, and what messages these visuals transmit about people to those viewing the artwork. Curator: Well, for me, it reveals so much about the economics and making of an artistic portrait in that time and speaks of a deliberate move toward greater accessibility of image production, and its consumption by many.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.