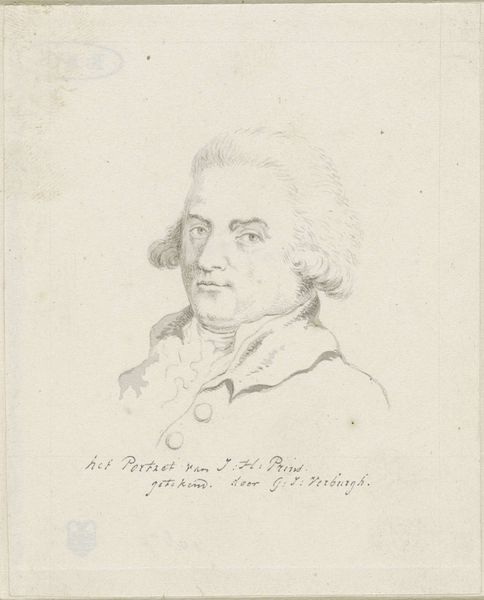

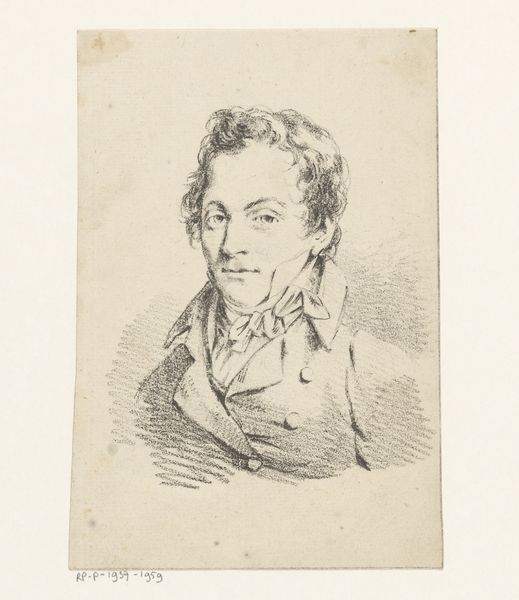

Dimensions: 113 mm (height) x 93 mm (width) (bladmaal)

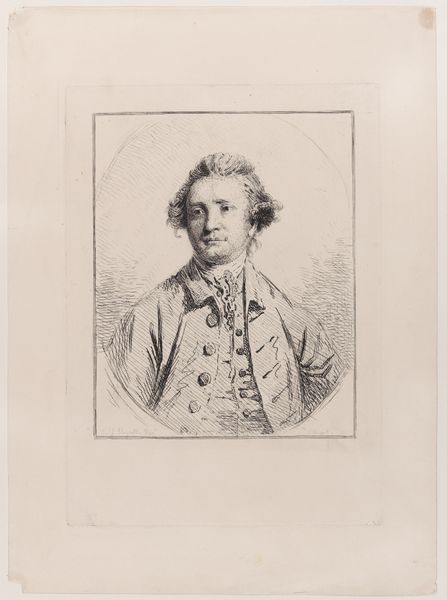

Editor: Here we have Johann Heinrich Schröder's "Self-Portrait(?)," created sometime between 1757 and 1812 using pencil. There's a softness to it, an almost dreamlike quality, and the material lends itself well to the romantic style. What strikes you most about this work? Curator: I find myself focusing on the materiality of the graphite and the artist’s process. Consider the social context: portraits like this became increasingly accessible due to advancements in graphite production, enabling artists – and aspiring ones – to produce likenesses without the expense of paint. Doesn’t this democratisation of portraiture speak volumes about shifts in societal values and self-representation? Editor: I suppose so. It's interesting to think about the pencil itself having an impact, not just the artist’s hand. Do you think this impacts our reading of Romanticism and individuality? Curator: Precisely! The very act of creating multiple iterations, experimenting with shading, the *labor* involved – this is all captured by the material. Pencil is inherently erasable, workable, which allows more artists access. It allows for preliminary drawings. Do you find these aspects impact our idea of romantic genius? The means of production directly informs how we interpret the art. Editor: I hadn’t considered how the materials themselves could challenge established ideas about artistic genius and originality. It really makes you rethink the whole social framework around art production at that time. Curator: Indeed! It's easy to get lost in iconography, but we have to acknowledge artmaking as labor. To engage with its history means interrogating social structures surrounding artistic production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.