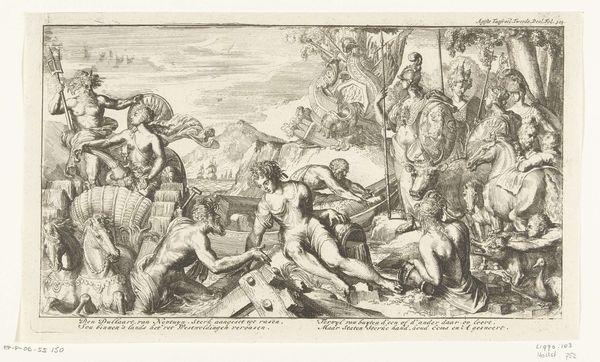

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

classical-realism

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

geometric

#

classicism

#

group-portraits

#

pen work

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 373 mm, width 537 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving, “Verzameling der Goden op de Olympus,” made around 1602 by Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio and now housed in the Rijksmuseum, I'm struck by how incredibly busy and populated it is. Editor: My initial impression is one of divine disarray. A bit too many bodies lounging on fluffy clouds, isn’t it? Like a celestial toga party after the wine’s run out. Curator: It’s certainly a far cry from the serene, orderly visions of Olympus we sometimes get. There's an element of Mannerism here, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Oh, absolutely. I think you can really see it in the contorted poses, and how Caraglio is treating his materials. Look at the fine, delicate lines of the engraving. You see that meticulous work repeated and repeated to get all these details in there. It shows not only craftsmanship, but the physical labor of producing images in that period. Curator: Exactly! The sheer detail is dizzying. Every god is crammed in with their identifying attributes... Jupiter’s eagle, Neptune’s trident, even a rather plump Cupid carrying a bag, presumably filled with arrows of love…or perhaps something less PG. The etching gives them a unified yet almost frantic feel. It reflects that era’s fascination and maybe anxiety of capturing totality. Editor: And it begs the question—for whom was this visual excess? This isn't just an image, but a produced object circulated amongst an elite, wealthy enough to engage with it. It serves a purpose beyond aesthetics. What statement are they trying to make? Curator: Perhaps a statement of possessing both wealth and classical learning? A declaration that they understood the mythology being represented? The Renaissance, Italian style, adored the classics, so these themes were status symbols. The scene almost reminds me of watching clouds. At first, you see specific shapes but then get lost in the complexity...like reading a symbolic puzzle. Editor: That's interesting...almost like deciphering meaning became a sort of commodity, and images like these, reproduced in print, offered exclusive access to that rarefied knowledge. This artwork doesn't merely represent a scene; it materially embodies social standing, craftsmanship, and a particular worldview from the 17th Century. Curator: Thinking about the stories, it now makes sense it looks slightly disorganized. I imagine divine drama isn't easy to orchestrate, whether you’re a god or an artist! Editor: Agreed, an apt and lively description and ending indeed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.