Dimensions: plate: 24.1 x 16.7 cm (9 1/2 x 6 9/16 in.) sheet: 38.2 x 26.6 cm (15 1/16 x 10 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

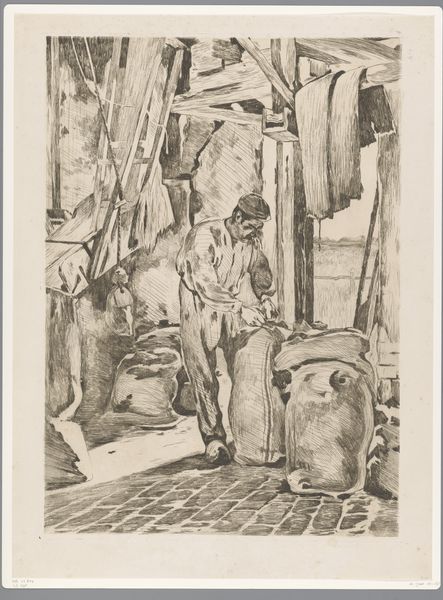

Curator: Giovanni David's "The Tired Wigmaker," dating back to 1775, presents us with a fascinating slice of 18th-century life, rendered through engraving, a type of printmaking. Editor: It's remarkably poignant; a simple scene, really, but evokes a powerful feeling of exhaustion, a very palpable human vulnerability. The wigmaker slumped in his chair has clearly had a very long day. Curator: Note how David uses the precise, linear quality inherent to the engraving process. It's all lines, really. From the intricate details of the wig hanging in the background to the tired slouch of the wigmaker himself. The entire scene is rendered meticulously. This was not a casual process but a structured one dependent on both labor and technical precision. Editor: Precisely! I mean, think about the physical effort just to achieve those seemingly simple lines and shades. And how brilliant to emphasize the weight of fatigue, by allowing it to almost escape the constraints of realism and veer into a pure emotional state! Look at how his smock hangs off his body. He looks drained and, I think, probably feels trapped by his work. Curator: The print as a medium in this era allowed for broader circulation, thereby capturing the working lives of everyday people like this wigmaker who, quite literally, made the artifice for the fashionable elite. There's an implicit commentary here, a glimpse into the social dynamics of labor and consumption. Editor: And consider the tools scattered on the floor—scissors, wig molds—the tangible reminders of his trade. Those implements really contribute to the intimate and somewhat messy nature of his profession and the weariness he likely experienced from dawn 'til dusk, constantly creating the perfect visage of the court, when all he truly wanted to do was just… rest. Curator: It is a window into a very specific moment, and the very fact that the engraving allows multiple copies means the commentary and David’s view become broadly available for the consumption of the 18th-century art world. It really provides context for that economy. Editor: It makes you consider the true price of beauty back then, doesn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.