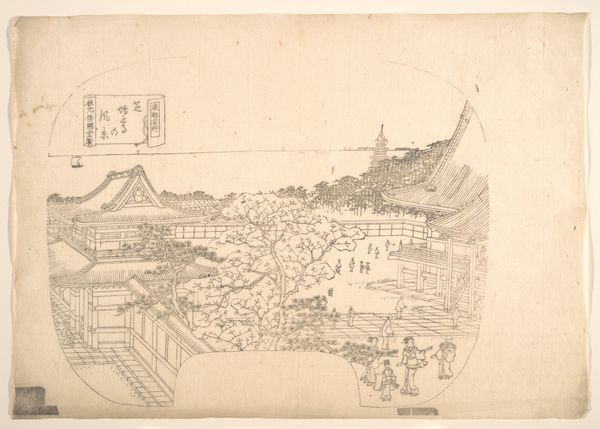

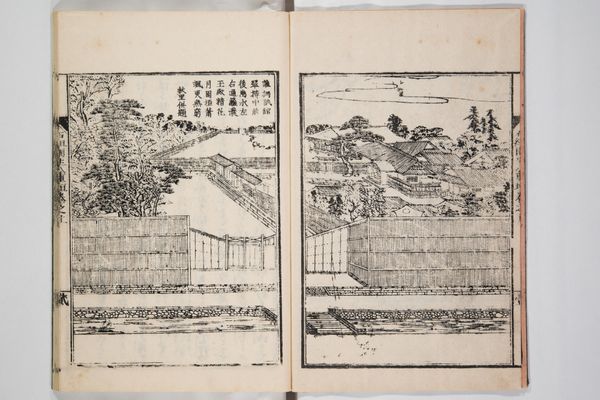

drawing, print, etching, ink, woodblock-print, woodcut

#

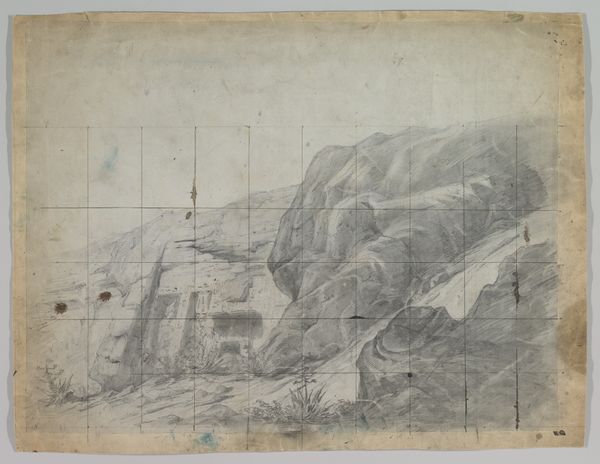

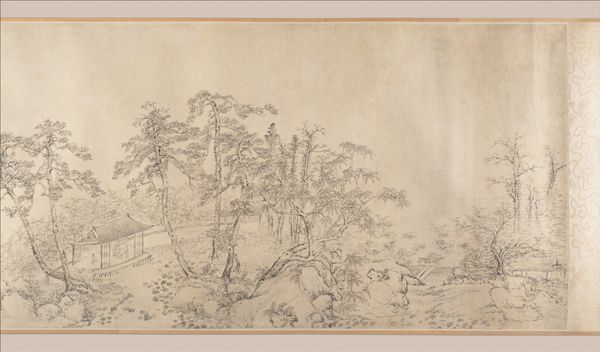

drawing

#

boat

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

human-figures

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

woodblock-print

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

woodcut

Dimensions: Image: 11 7/8 x 9 1/2 in. (30.2 x 24.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have "Proof Line-Block Print for Fan," made between 1807 and 1879 by Utagawa Sadahide. It’s currently housed here at the Met. The print depicts a bustling scene along a river, maybe a festival. I am especially interested in the lines. What social or historical contexts can you tell us about this work and it’s meaning? Curator: Well, consider ukiyo-e, the floating world. Prints like these weren't simply aesthetic objects. They reflected, and in turn shaped, popular culture in Edo-period Japan. Fan prints especially, were ephemeral objects of mass consumption. It begs the question: What kind of social rituals, or entertainment practices are being visually promoted here? Notice the figures on the bridge, seemingly in joyous commotion – what do you make of that imagery? Editor: It does seem like a festive gathering! They're maybe celebrating something? How would the general public have reacted to such images? Did these prints play a specific role in disseminating ideas or values? Curator: Exactly! Consider the rapid urbanization of Edo, and a growing merchant class eager for entertainment. These prints offered them glimpses into desirable lifestyles and events. The imagery normalizes behavior. Think about the interplay between art and social aspiration – who has access to art and media shapes how trends happen, don't you think? Who benefits? These line block prints, so readily accessible, effectively democratized the art world. Editor: That's fascinating. So the medium itself—the accessibility of the print—played a vital role in its cultural impact? It highlights art’s public role. I'm now curious to examine more of Sadahide's work through the lens of social history! Curator: Indeed! By thinking of art as embedded in socio-economic circumstances we better grasp it’s meaning, its public purpose and the politics of imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.