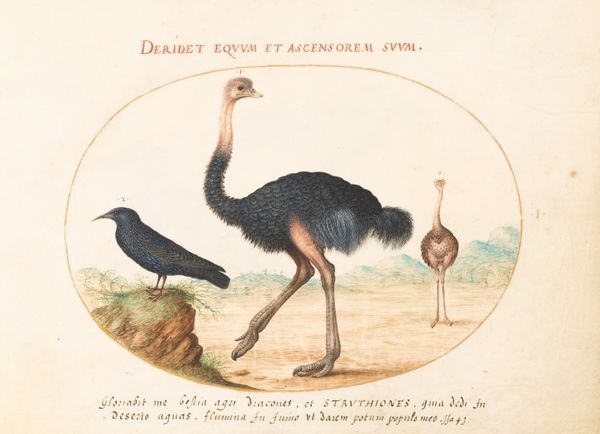

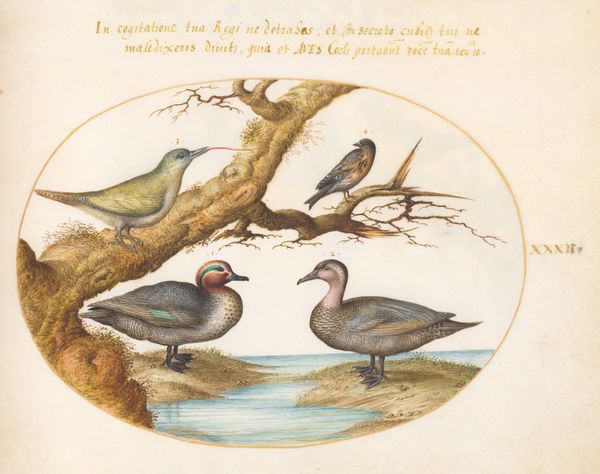

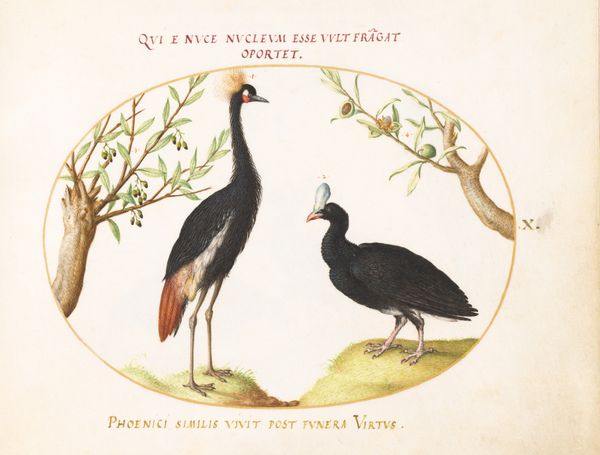

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

botanical illustration

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

botanical drawing

#

northern-renaissance

#

academic-art

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Look at this exquisitely rendered watercolor and ink drawing from around 1575-1580 by Joris Hoefnagel titled, "Plate 14: Spoonbill Crane and Flamingo." It’s a real feast for the eyes. Editor: It's strangely calming. The birds feel like emblems more than portraits; a sense of timeless serenity emanates from the crisp detail. And there is some text, let me see. Curator: Yes, Hoefnagel's work fits squarely within the Northern Renaissance tradition, an era deeply influenced by Humanism. The imagery of animals becomes not just about depiction, but a mirror to human nature and society. In fact, this illustration along with other similar illustrations accompany some latin scripture or biblical references, it reads *SIMILIS FACTVS SVM PELLICANO SOLITUDINIS* which references Psalms 101 which states "*I am like a pelican of the wilderness*". Editor: Exactly, that pairing reinforces the weight of the depicted imagery. Consider how the Spoonbill, presented against what appears to be the wilderness, and Flamingo become vehicles of profound cultural meaning. Medieval bestiaries assigned varied significances to birds: the pelican's self-sacrificial feeding its young with its own blood symbolizes Christ's sacrifice; flamingo's could easily relate to concepts of beauty, purity, or even vanity based on color. The Latin text included at the bottom really speaks to that Pelican mythology. Curator: Right. The Pelican's blood sacrifice, of course, alludes to ideas of religious devotion and sacrifice which are notions deeply embedded in societal constructs. These images became powerful political tools as well. Consider that wealthy families began adopting heraldic bestiaries as markers of lineage during the period and that shaped what visual art was commissioned and seen. These birds become symbols used for propaganda as much as personal branding. Editor: It’s all so deliberately chosen. And that dragonfly near the flamingo's wing further enriches this natural allegory – a fleeting existence. There is this memento mori quality to it. Curator: Precisely. We get these little markers to tell a more expansive story. This wasn't just artwork to hang but tools to assert moral guidance within society, really controlling narratives of piety or appropriate behaviour and family dynamics, Editor: A powerful synthesis of symbolism and observation, shaping cultural consciousness through nature's lens. Curator: Indeed. Looking at it from this perspective gives so much depth to appreciate how imagery functions beyond mere artistic creation but truly becomes enmeshed with historical contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.