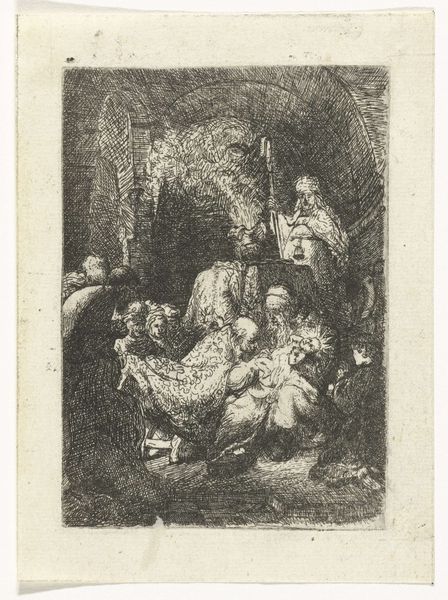

print, etching

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

Dimensions: height 73 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are standing before Jan Lievens’s etching, "The Idolatry of Solomon," dating sometime between 1625 and 1674. It's a small print, but dense with narrative. Editor: Intensely shadowed, isn't it? It feels almost claustrophobic, with this oppressive sense of darkness looming over the scene. I'm struck by how deeply carved the lines are to convey that. Curator: Exactly. Note how Lievens employs hatching and cross-hatching, particularly in the upper portion, to create this effect. The formal arrangement funnels our eyes to Solomon and his figures, a calculated semiotic composition that guides our gaze. Editor: Speaking of materials, I am curious about how the etching process informs our reading. You've got this rather immediate relationship with the copperplate—how the artist's hand physically interacted with it to create these impressions of depth and shadow, revealing the means of its production. The physical process, in my opinion, mirrors Solomon’s own corruption—a gradual degradation etched over time, as he succumbs. Curator: I understand what you are pointing out, although that seems quite an intentional allegory when perhaps we could simply discuss Solomon as the subject, rather than the material qualities. But this leads to an important philosophical matter that has captured minds for generations. We find through his figuration here a cautionary biblical tale; how unchecked power or desire, here of foreign wives, can dismantle even the wisest leader, no matter what the costs are to craft such material and allegory for one of history’s most legendary men. Editor: Precisely, and that connection to materials further ties it to a specific socioeconomic moment, an insight to what types of labor went into producing art like this for circulation, too. Was Lievens making a subtle critique of patronage and artistic labor of the day, as much as of Solomon? Curator: A compelling consideration that I concede, with that said, leads us back to the present, questioning the power structures inherent in the creation and consumption of art itself. Food for thought on Lievens' technique to be sure. Editor: Absolutely, the conversation about art’s creation remains a vital link between then and now. Thanks for joining me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.