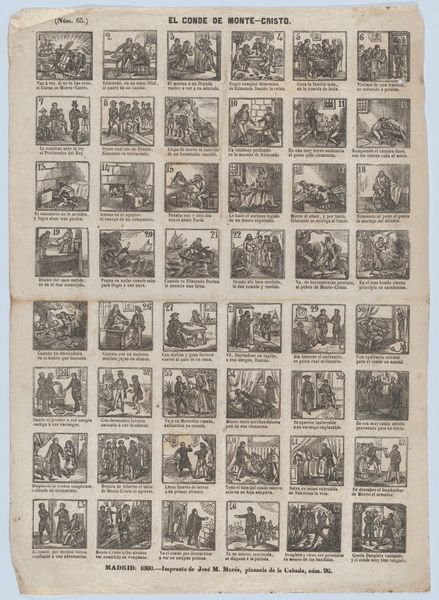

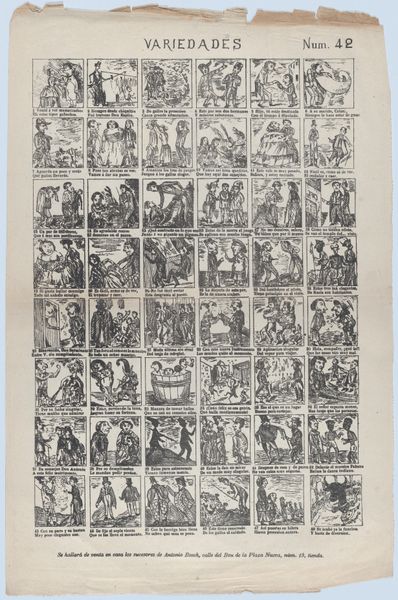

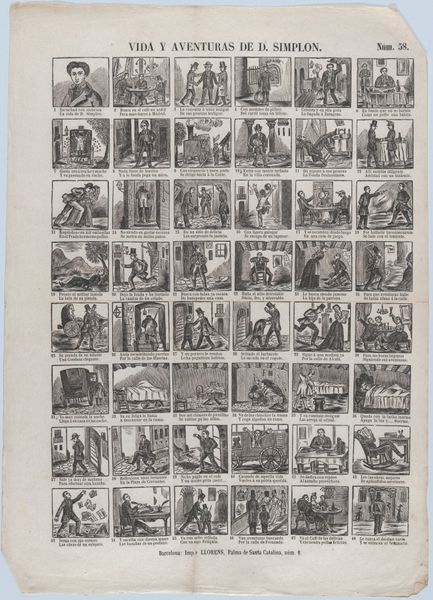

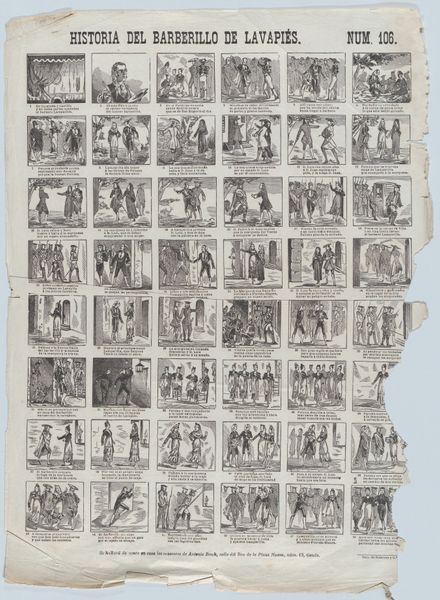

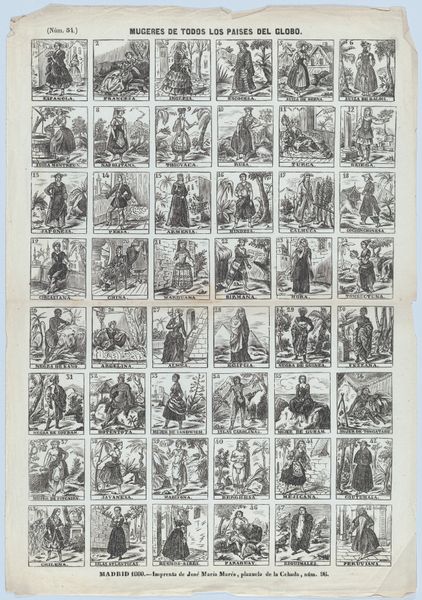

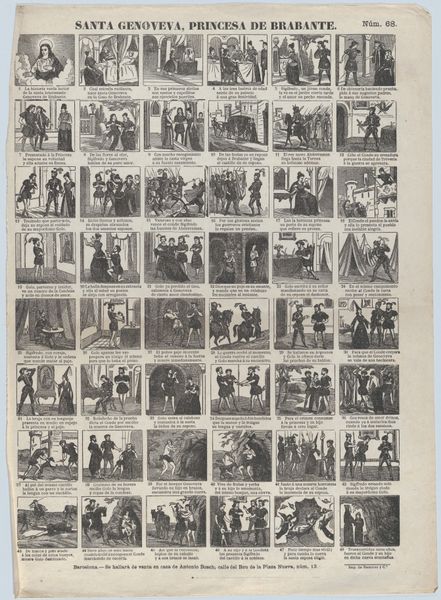

Broadside with 48 scenes depicting the life of a servant girl 1859

0:00

0:00

drawing, graphic-art, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

page thumbnail

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

journal

#

ink colored

#

men

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

columned text

Dimensions: Sheet: 17 5/16 × 12 3/8 in. (44 × 31.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

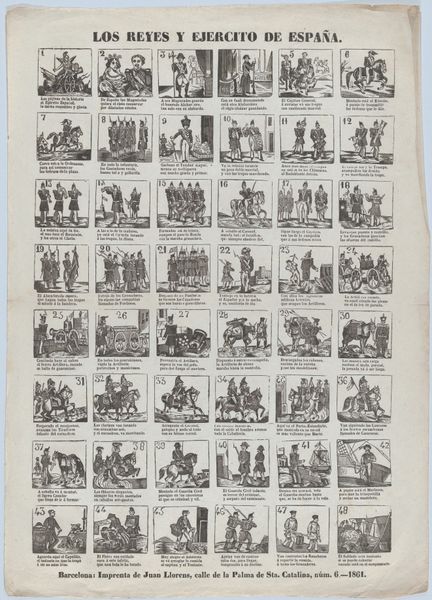

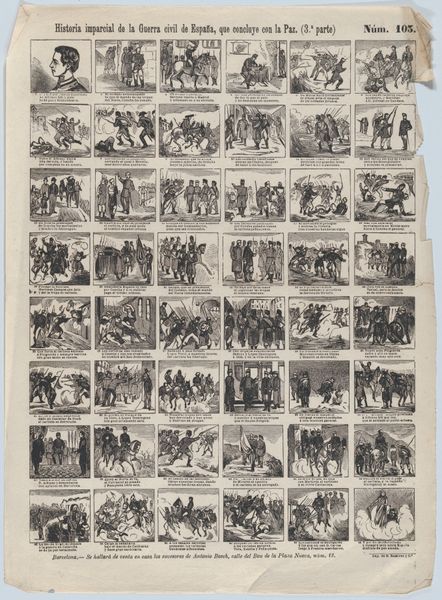

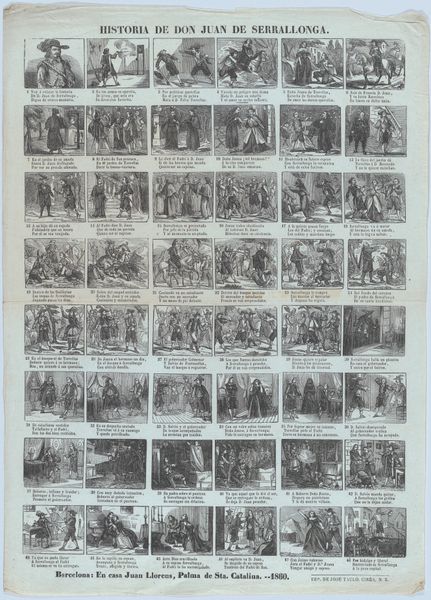

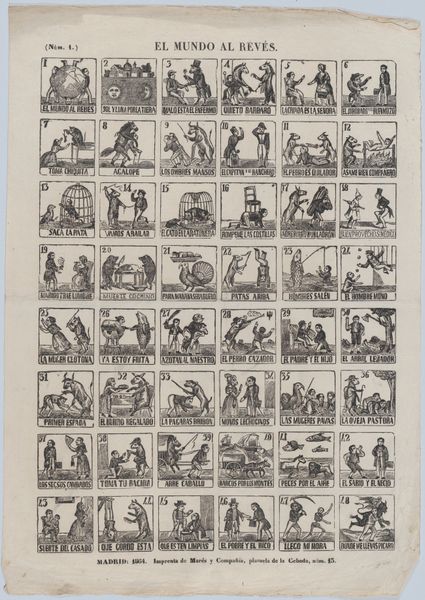

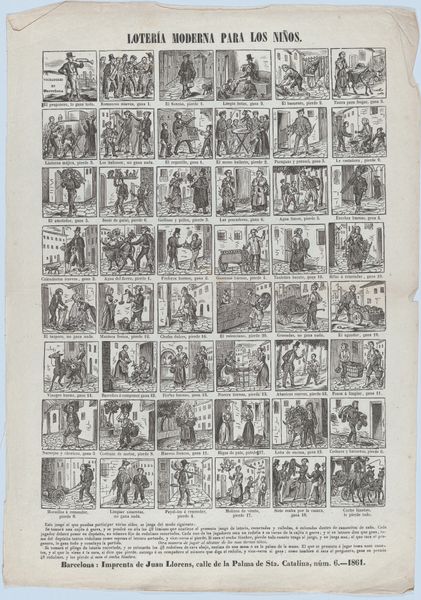

Curator: Looking at this intriguing 1859 broadside titled "Broadside with 48 scenes depicting the life of a servant girl" by José María Marés, currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, my immediate impression is one of dense, almost overwhelming detail. It’s a whole world encapsulated on a single sheet of paper! Editor: Overwhelming is an apt description! There is a stark, cautionary atmosphere created by the repetition and contrast. Each little vignette pulses with stories of domestic life— mostly mundane, but certainly all steeped in the symbols of service and constraint. It’s a visual onslaught that hints at social confinement. Curator: Indeed, Marés has created almost a comic strip, but one charged with historical commentary. We must remember that this broadside isn't merely descriptive; it's a socio-political document speaking to the role, and likely the plight, of servant girls in 19th-century Madrid. Its materiality - ink on paper - lends a gritty realness. Editor: Absolutely, consider the symbolic resonance of the girl being positioned within boxes or cells, and of the prevalence of daily chores turned ritual acts, devoid of autonomy. Also the choice of presenting it as a “broadside”. Its nature indicates this object was mass produced for a public audience. Why? What message were people meant to derive by gazing into this sequence of oppressive drudgery? Curator: A crucial question! It hints that the scenes depicted may not have been hidden, private or secret. In turn the repeated image of the serving class reminds the bourgeois spectator not only of the benefits received as employers, but of their proximity to social others, their need of others' hard toil and suffering, the foundation of society itself, and ultimately perhaps, the possibility of its inversion. Editor: I find it unsettling how the repetitive nature almost desensitizes us to her situation, reflecting a wider indifference perhaps inherent within society at the time. This could be the artist's commentary to how easily we might dismiss a whole social segment, unless images of suffering move our emotions or raise ethical questions. Curator: A valuable observation. Ultimately, it suggests a certain ambiguity in the visual symbolism on view; it asks us to probe beneath the veneer of daily life of the era to consider the undercurrents of its society. Editor: Right. It shows the value of using visual and material cues in exploring not only how an artwork is understood, but also its role as a mirror reflecting power structures of the age. It urges one to think what would be missing should there not be constant scrutiny of an artwork as a public document with specific purpose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.