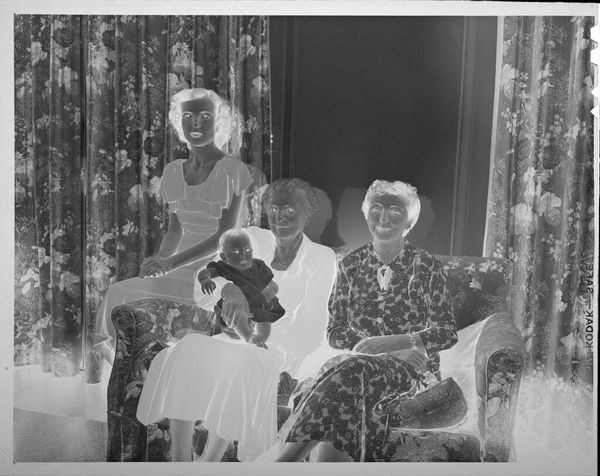

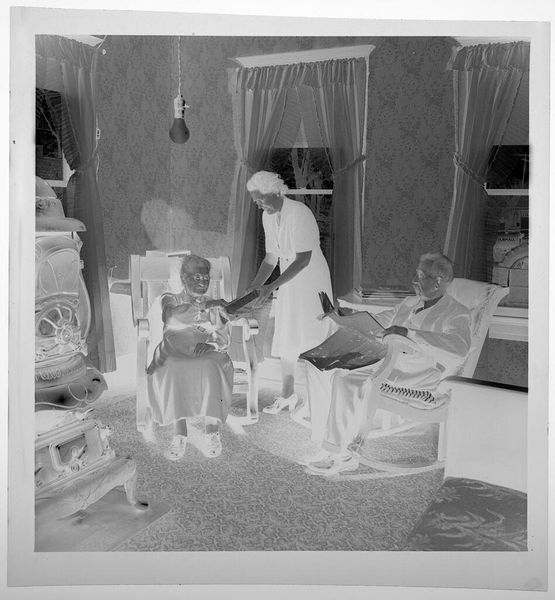

Mother, Daughter and Maid, Johannesburg, South Africa Possibly 1988 - 1993

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

film photography

#

black and white photography

#

social-realism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

modernism

Dimensions: image: 38.7 × 38.4 cm (15 1/4 × 15 1/8 in.) sheet: 50.5 × 40.3 cm (19 7/8 × 15 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Rosalind Solomon’s "Mother, Daughter and Maid, Johannesburg, South Africa" offers a compelling, though potentially problematic, snapshot of life during apartheid, sometime between 1988 and 1993. What strikes you first about this gelatin-silver print? Editor: The starkness. It's more than just the black and white. The way the three figures are arranged – almost staged – highlights social divisions in very deliberate visual terms. The domestic setting feels both intimate and deeply unsettling. Curator: Exactly. This photograph is not merely a portrait; it's a careful construction of social relationships, rife with the legacies of colonialism and the ongoing realities of racial and economic inequality. The maid's placement on the floor, separate and subordinate to the white mother and child elevated on the chair…it speaks volumes. Editor: And consider the interior itself – the patterns, the textures, the domestic objects. This space is furnished with consumer goods – the TV, the boombox. These goods were made through exploiting labor from people forced to work in terrible conditions, perhaps, like the domestic worker we see. The materials in this room tell a whole history of social making and of global production. Curator: That’s precisely what makes this photograph so compelling – and uncomfortable. We must ask: What was Solomon's role as a photographer within this dynamic? Was she simply documenting, or was she complicit in reinforcing these power structures? It asks for reflection on her methods and motives. Editor: It really forces us to look at the mechanisms of how domestic labour operates as this exploitative act – seeing her forced presence and comparing her to the casual presence of leisure held by the daughter, especially. It allows us to trace those material relations so present in how labor plays out and the visual terms we assign it through items we purchase to ease life. Curator: And the expressions! The ambiguous smile of the mother, the uncertain gaze of the child, the maid's seemingly blank stare...are these accurate representations of the individual feelings, or do they fall back on harmful, longstanding stereotypes? Editor: I think we really need to push past looking at her laboring position in terms of emotional quality and turn toward the more pertinent matter of her alienation as a subject – something that we can extract from her proximity to all these leisure-geared objects and furnishings and situate the making of as conditions to be considered when thinking of material life. Curator: Yes, it truly is complex. Editor: And troubling, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.