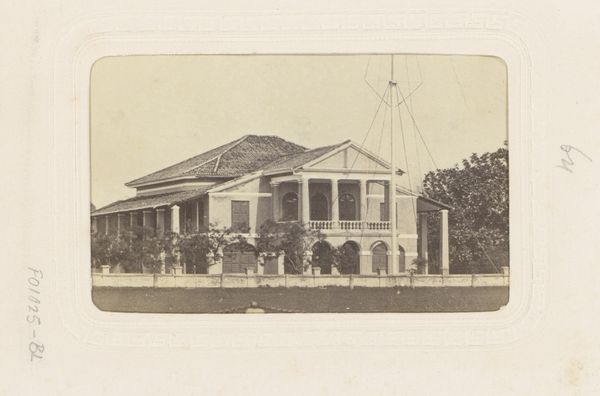

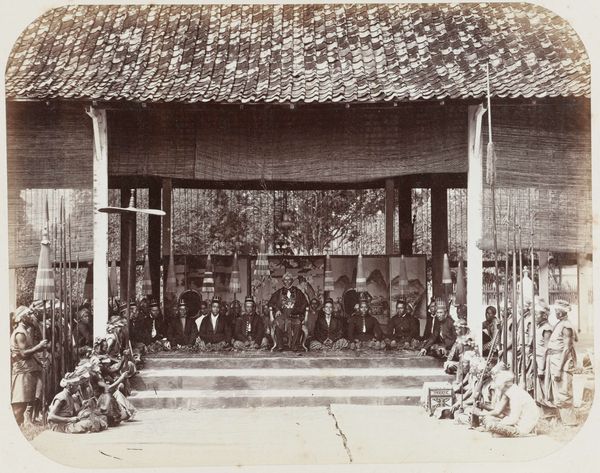

albumen-print, photography, albumen-print, architecture

#

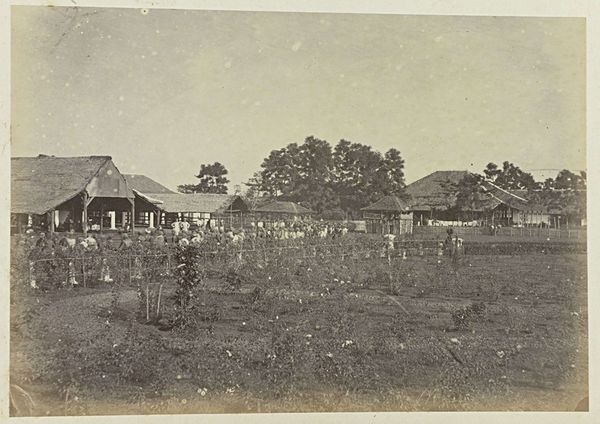

albumen-print

#

etching

#

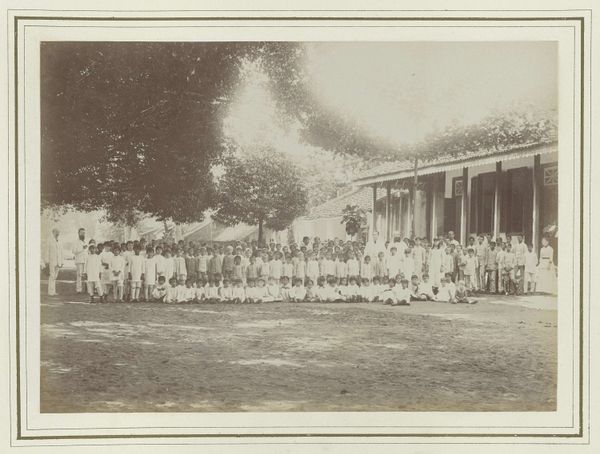

photography

#

group-portraits

#

orientalism

#

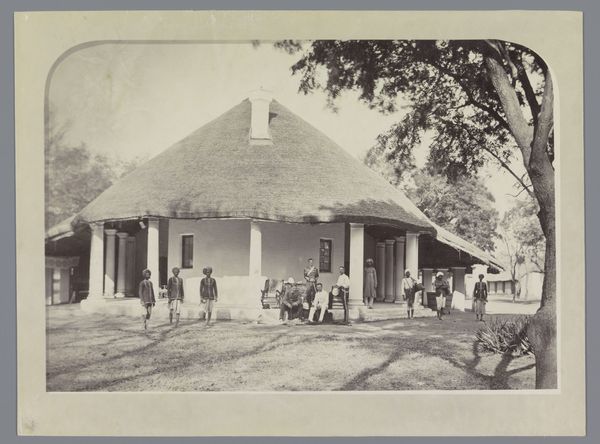

albumen-print

#

architecture

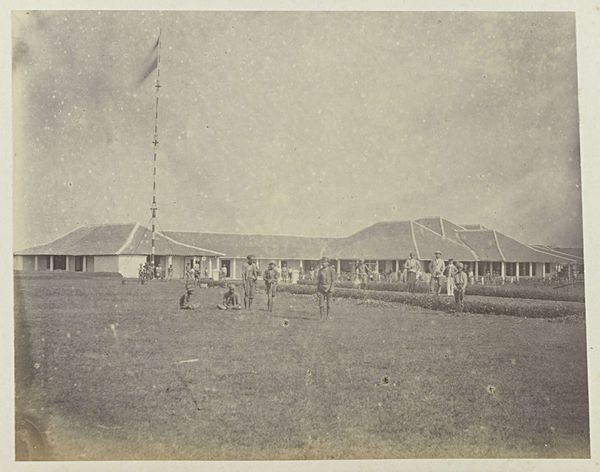

Dimensions: height 161 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: "Decoraties bij bezoek," or "Decorations for a Visit," a photographic print dating back to between 1863 and 1869, attributed to Woodbury & Page. You can currently find it within the collections of the Rijksmuseum. What is your first impression? Editor: Well, it feels incredibly staged. I mean, it's grand, sure, with the imposing architecture and a throng of figures, but there's also this strange formality that almost feels… sterile? Like a movie set more than a moment captured. Curator: Yes, "staged" is a keyword here. In photographs of this era, we're seeing the codification of visual representations of power and cultural dynamics at play. This albumen print reflects an orientalist style, prevalent during that time, attempting to document but inevitably also framing its subject through a colonial gaze. The decorations, the landscaping, and the positioning of people all contribute to constructing a certain narrative. Editor: The poses and expressions seem so rigidly controlled. Everyone is facing the camera as if trapped. You have to wonder about the individuals themselves—what stories do they hold? What meaning did the decorations carry for them versus the photographers documenting it? Curator: Indeed. Think about the swirled, white decoration draped from the porch supports... what does "decoration" mean here, and for whom? It could symbolize festivity but simultaneously mark cultural difference. In these contexts, symbolism acts as a social shorthand, perpetuating and encoding views and power relationships. Editor: Absolutely, it’s like the photograph freezes an unequal dynamic. On one hand, we have this intriguing peek into the lives and aesthetics of the Asian aristocracy; on the other, we have the weight of a Western lens capturing it all for consumption back home, where audiences undoubtedly assigned entirely different meanings to every symbol. Curator: Photography, in its early days, becomes an instrument for classifying the world. This image preserves a moment, certainly, but also solidifies specific ways of perceiving identity, class, and culture across geographical distances. Editor: It's an uneasy beauty, this image. It beckons you in, but also reminds you that it doesn't tell a simple story. It feels charged with layers that invite constant unraveling. Curator: Precisely. Photographs like these become points of departure, invitations for us to look critically, asking, "Whose story is being told, and how?" The layers, those are precisely what compel continued consideration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.