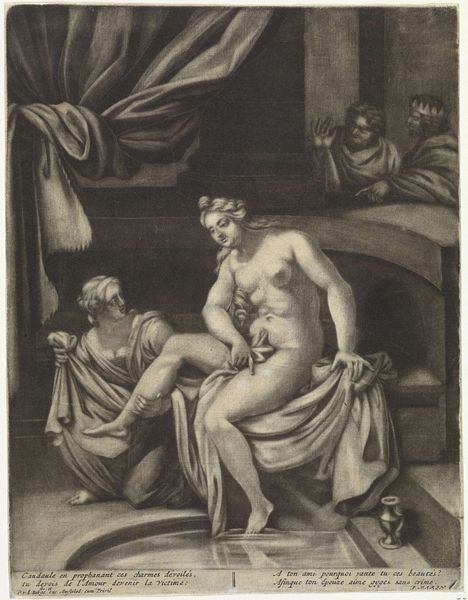

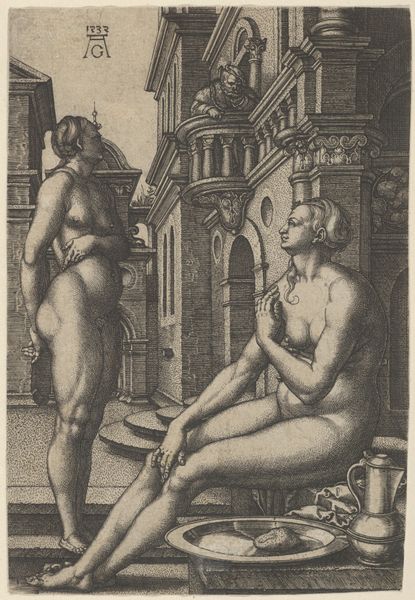

The toilet of Psyche who is seated in the centre being attended to 1531 - 1576

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 8 11/16 x 6 1/4 in. (22 x 15.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing here, we’re observing Giulio Bonasone’s engraving, “The Toilet of Psyche who is seated in the centre being attended to," created sometime between 1531 and 1576. Editor: My first impression is the incredible intimacy of it, even with the classical subject matter. It’s all soft curves and almost hesitant gazes, but there is a voyeuristic quality too that keeps you looking. Curator: Exactly. Italian Renaissance engravings like this one served a vital role in disseminating classical imagery and stories. Bonasone, like many printmakers of his time, aimed to make these mythological scenes accessible. In a way it democratized art! Editor: It's quite potent, though, considering its medium is something so easily reproduced. What intrigues me most is how vulnerable Psyche appears here, yet the attending figures barely acknowledge us—they're absorbed. Almost as if beauty, being prepared, is in itself a private affair. Curator: The scene also speaks to the socio-political structures that upheld these notions of beauty. The commodification of female beauty in art certainly flourished in the Renaissance. Think of how courtly rituals are being replicated here for an unseen audience. Editor: Perhaps. I’m drawn more to the humanity though—the textures in the skin suggested through these etched lines, or the weight of the fabric pooling around Psyche's waist. These tiny details pull at something tender in me, as though I know these women, but I never will. Curator: Absolutely. Engravings, despite their replicative nature, still offer opportunities for expressive mark-making and nuance. The success of art such as this rested in how well the story spoke to the current societal standards and aspirations. Editor: This little vignette becomes a meditation on transformation, a physical and symbolic grooming before love, maybe before scrutiny. Is there more truth in observing Psyche's discomfort, as opposed to any supposed beauty of transformation and appearance? I don't know... But my sense of that remains after looking at this, maybe I felt the same as the women on view. Curator: Indeed, we're left with a portrait, and in this one you cannot fail to see its significance. What it signifies to those in the early 16th century in their contemporary setting and, as you touch on, what the engraving signifies now in the present, as you grapple with ideas of beauty and societal influence. Editor: Well put. It is rather moving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.