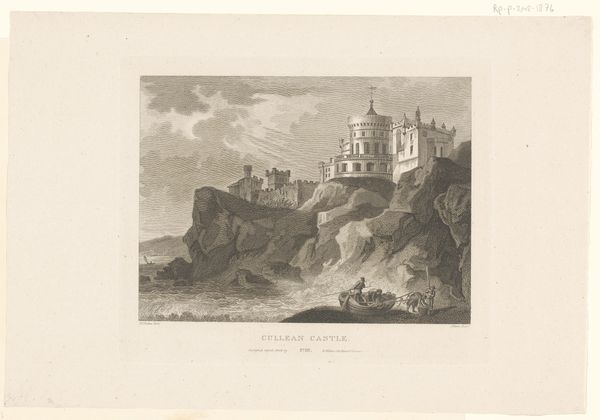

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 450 mm, width 567 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

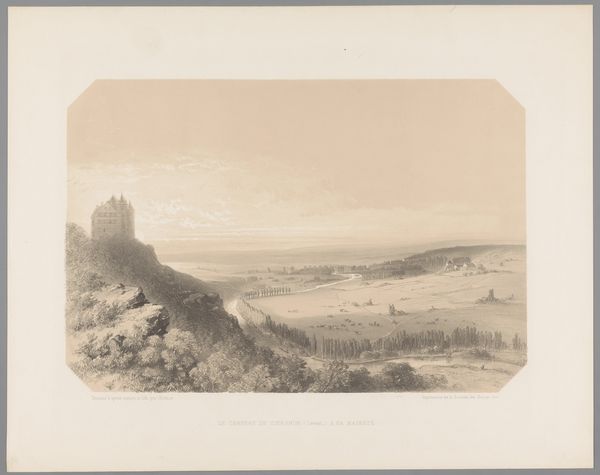

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this serene view, "Gezicht op het koninklijk kasteel van Ciergnon," created by Louis Ghémar around 1846. It's an engraving, offering us a glimpse of the Belgian royal residence. Editor: It feels quite… subdued. There's a formality to the composition, a kind of quiet grandeur with those muted tones. The castle feels like a watchtower observing an ideal countryside, all rendered with painstaking precision in monochrome print. Curator: Precisely. As an engraving, the level of detail Ghémar achieves speaks volumes about the labor involved. Consider the tooling marks, the precise lines creating texture, light, and depth, how materials are carefully burnished in different gradients of light... it underscores the artistic craft in this reproduction. The material itself conveys prestige and durability. Editor: The castle, of course, is the key. Set high above the manicured fields. Its architecture carries an implicit message of power and permanence, and it looms like a protective emblem of a kingdom overlooking orderly fields. Is there any information on the significance of Ciergnon at the time? Curator: Ciergnon was becoming an increasingly important summer residence for the Belgian royal family at this time. This print would have served as both documentation of and publicity for the site, solidifying its place in the public imagination. The print is a commodity produced for consumption. Editor: You see a claim of royal place and order. It's a highly romanticized view that makes me think about landscape traditions depicting ideal states. Consider those figures, perhaps royal, in the foreground--almost reverent as if they gaze out towards an unearthly, almost ethereal seat of kings. What is nature serving here, if not as a testament to enduring, ordered governance? Curator: Exactly, and the production of such images contributes to that image-building enterprise, turning this castle into a national treasure, materializing through the mass production of prints. It really bridges notions of place, rulership, labor and nationhood in ways that other modes do not allow. Editor: So it’s about visibility? In that way, printmaking, even an ostensibly neutral depiction of a castle, is active propaganda and promotion of a dynasty and nation? Curator: Yes! And so we should consider what this specific artistic craft made available, materially, to a rising state at mid-century. Editor: Looking closer, then, moves us from awe to analytical interest. The way an image is consumed changes when you reveal its workings and its time, thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.