drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

pen illustration

#

figuration

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

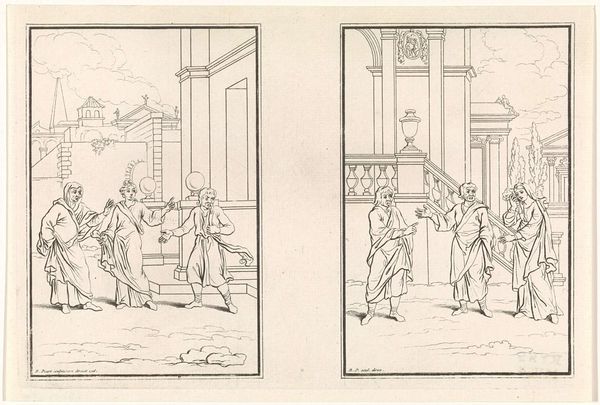

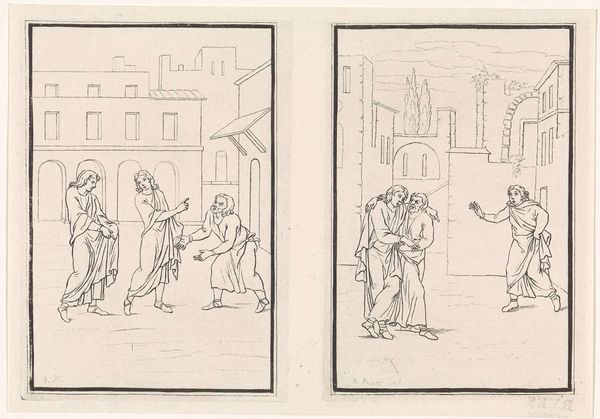

Dimensions: height 131 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

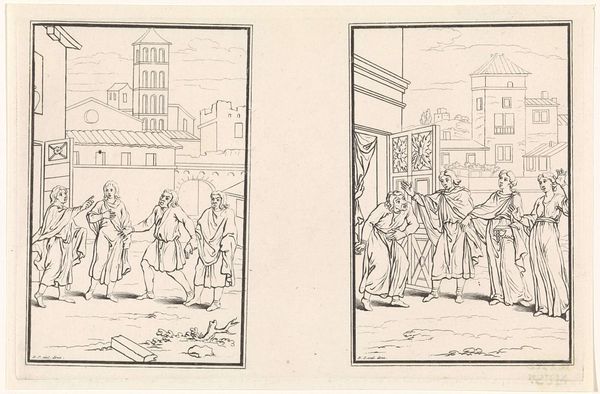

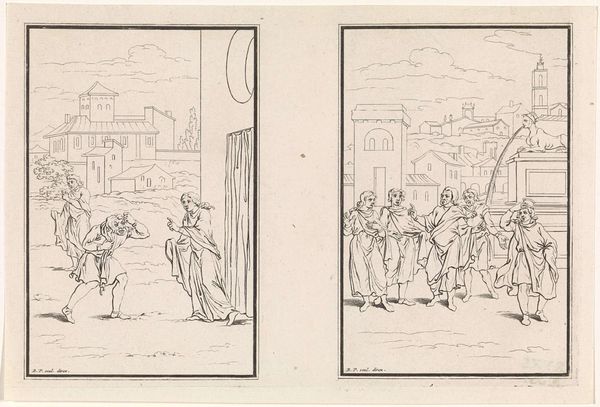

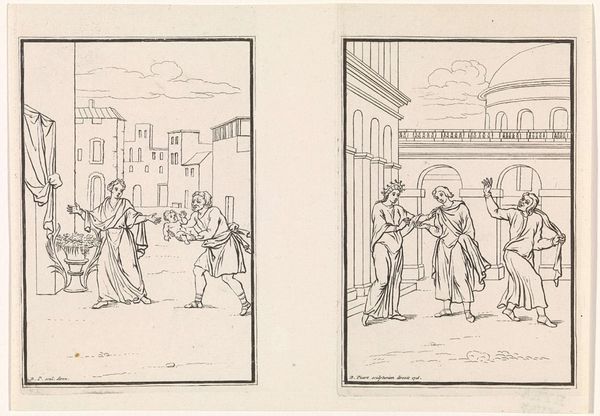

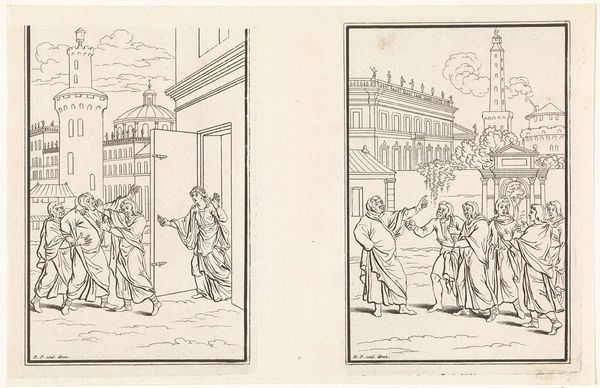

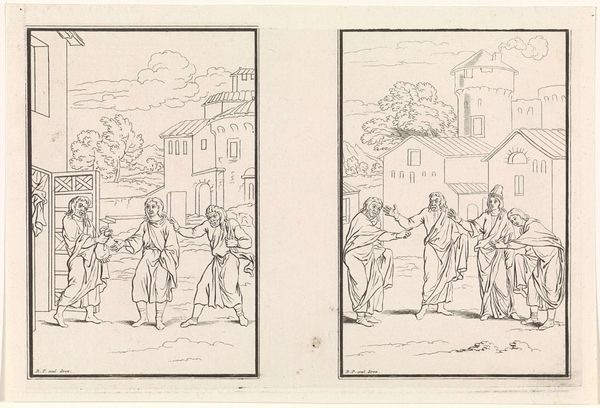

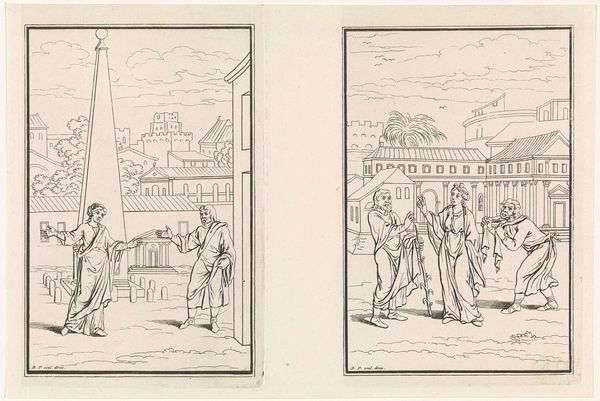

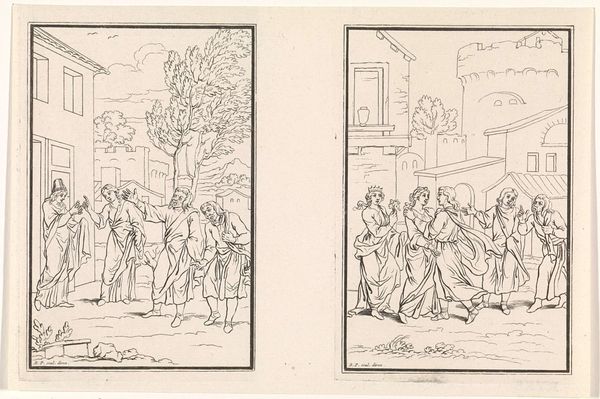

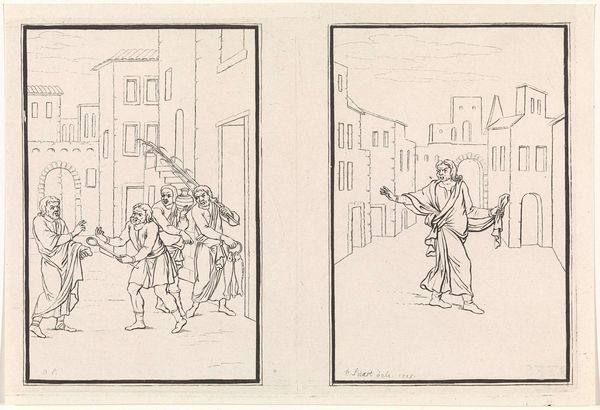

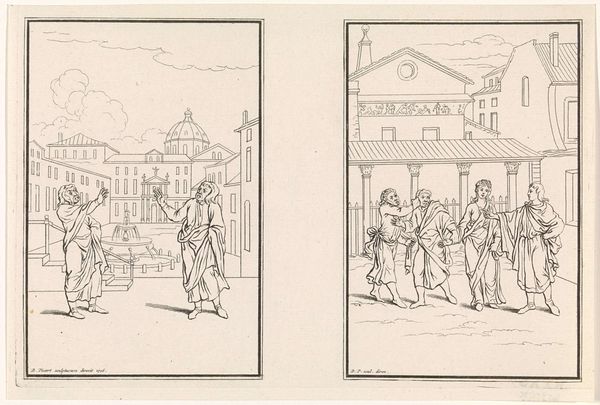

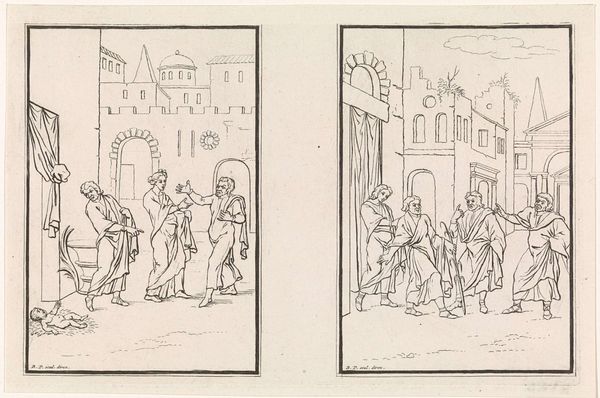

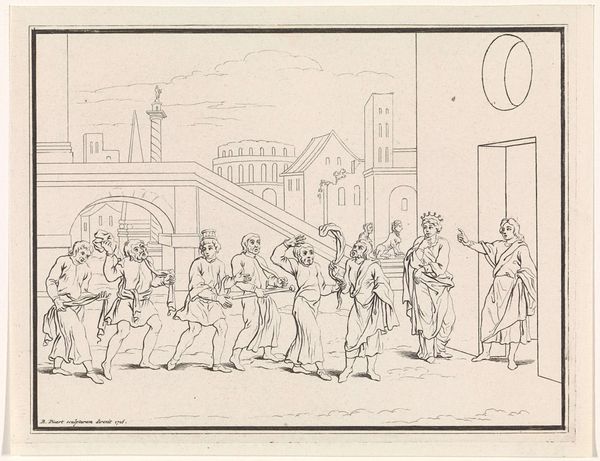

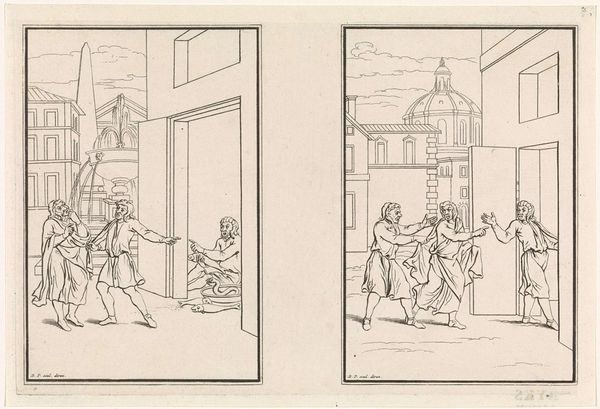

Curator: At the Rijksmuseum, we’re standing before a drawing titled "Twee scènes uit de komedie Eunuchus van Terentius," or "Two Scenes from the comedy Eunuchus by Terence," created between 1716 and 1718 by Bernard Picart. It's a fascinating ink and pen illustration rendered as an engraving, depicting two separate yet interconnected scenes. Editor: My first impression is one of classical drama brought to life with clean lines. It feels very stage-like, the composition directing my eye through a series of carefully arranged figures in two separate frames with the same linework, as though I’m watching two parts of the same stage play unfurl at the same time. Curator: Indeed. The narrative aspect is quite prominent. Picart wasn’t just creating art; he was engaging in a form of visual storytelling tied directly to Terence's play, one of the classic comedies in the Western theatrical canon, so this drawing asks the viewer to reckon with complex histories of gender and class structures from a distant point in history. Who is afforded agency in these images, who is not, and who dictates what the “rules” of these interpersonal games are? Editor: The imagery speaks of codified performance. We see robes and gestures, and immediately place them into a certain context of high society, with symbolic garb marking their places in Roman society. You know, even in a sketch so light and minimal, it communicates so much about cultural expectations surrounding appearance. Curator: Absolutely. This engraving speaks volumes about Baroque-era sensibilities regarding class and identity, even now, the theatrical element highlights how so much social performance has survived across the ages and continues today. It begs questions of who can play what part, which characters can enter the scene and exit. Editor: The symbols present remind me of other engravings and drawings that served as visual aids, either educational or performative – that this, itself, is documentation *of* the performative nature of daily Roman life! Curator: Looking closely, you can see how the artist, Picart, really used line to portray not only the form of the figures, but the dramatic tension of this comedic story in a really unique rendering. Editor: Well, this piece has made me want to look even deeper into the world of visual symbolism in theatrical traditions, for what’s been brought to the stage or erased, and, of course, reread Terence. Curator: For me, it's a potent reminder that these so-called comedies, even centuries later, continue to provide ample material to examine structures of power and performance— both theatrical and political.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.