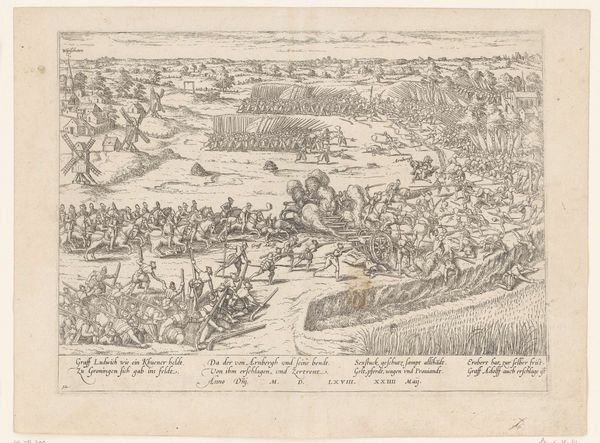

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 279 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes you first about this image? Editor: The sheer busyness of it all! My eyes dart around trying to take in the swirling mass of soldiers, the ordered lines, and the chaos of the battle itself. Curator: This is an engraving titled "Slag bij Heiligerlee, 1568," made sometime between 1649 and 1651. It commemorates the Battle of Heiligerlee, a key event in the early stages of the Eighty Years' War. Though the print is anonymous, it is preserved in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Ah, so that explains the intensity! It is very graphic in that old engraving style. I see symbols of power and faith scattered throughout; a windmill, I believe and various flags or banners which I imagine designate national and regional factions involved in this conflict. It evokes the period’s fervent political and religious ideologies clashing on the battlefield. Curator: Indeed, the work’s composition served as powerful propaganda. As a history painting intended for broad distribution, it needed to visually represent the Dutch victory. The artist uses visual shorthand, symbolic architecture in the background, with the textual key to denote specific moments and people during the event, so that it can serve as a political tool to boost national sentiment. Editor: The use of line is remarkable, so meticulous and precise. And then there’s the implied emotional weight of a pen sketch depicting such a fierce clash. Did the symbols offer people emotional stability during the wars? What continuous cultural meanings are sustained when translating from lived event to such iconic symbol laden sketches? Curator: Well, you could argue that historical images such as these were a new form of public memory that took hold alongside more ancient traditions of remembrance. Engravings could be printed and distributed widely, unlike monumental paintings of the era. The availability democratized national identity by making such imagery available outside of elite and court circles. Editor: Yes, the symbols here tell a compelling and layered story and speak volumes of its historical position in visual culture. I walk away seeing a visual encoding strategy rooted in the battle, but blossoming in a newly accessible printed cultural lexicon. Curator: Precisely. It’s fascinating how a relatively small print could exert such influence on collective memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.