tempera, print

#

aged paper

#

art-nouveau

#

tempera

# print

#

landscape

#

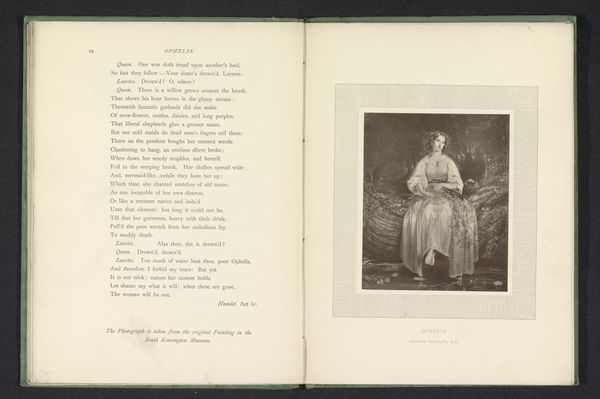

figuration

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 236 mm

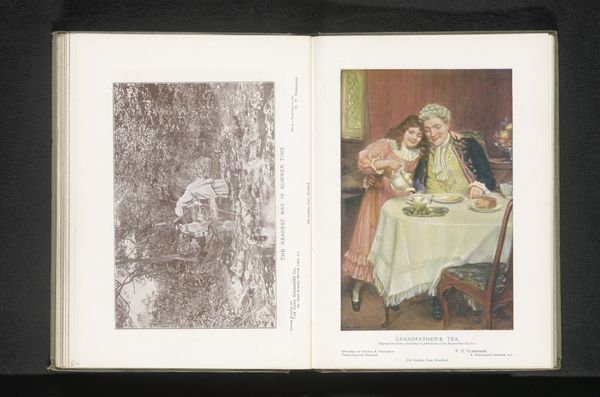

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Zes proefdrukken voor 'Kate Greenaway's Almanack for 1892'," a print by Edmund Evans dating to before 1891. It looks like it’s made with tempera. Editor: It has a certain fragile charm, doesn't it? The figures, so delicately rendered. It almost looks like it belongs in a children's book, but I sense more layers of complexity beneath the surface. Curator: These almanacs were highly popular. Evans was, of course, the key engraver and printer for Greenaway, which is itself an industry built around her particular brand of nostalgic childhood. What you're seeing here are essentially working proofs. They show the material labour behind those appealing final products. Editor: It’s interesting to consider the print as commodity then. The mass appeal indicates shifts in popular tastes, specifically around childhood and decorative arts. The integration of text and image – each month’s calendar beside a seasonal figure - points towards art’s expanded function within daily life. Curator: Absolutely, the choice of tempera is important here too. While a relatively quick medium, tempera required the building up of pigment layers; each proof a negotiation between efficiency for mass consumption, and Greenaway's desire for a distinctive aesthetic, made repeatable via mechanical reproduction, under Evans's practiced direction. Editor: I wonder how audiences engaged with these images at the time? Were they perceived as simply functional, or did they carry symbolic weight? Perhaps these representations of idealized womanhood, linked to different seasons, were subtly influencing societal views, reinforcing certain notions of femininity. Curator: Greenaway’s art existed firmly within a Victorian gift-giving economy, with printing being integral. Consider, what was the labour investment compared with other modes of image distribution, such as individual watercolours or small lithographs produced in artist-led ateliers? How did the price of this colour print make it accessible to wider audiences than a unique art object? Editor: This close consideration allows us to trace shifts within popular imagery and the industrial machinery supporting it, expanding from initial reception of imagery, now towards how that artwork, like this one, gets archived and exhibited in museum spaces over a century later. It serves to illuminate the evolving social and artistic ecosystems, even if the artist is now long gone. Curator: Agreed. It reveals much about the industrial means of aesthetic expression available at the time. Editor: It's given me a fresh perspective on Victorian visual culture and Greenaway’s reception in our era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.