photography, architecture

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 266 mm, width 201 mm, height 329 mm, width 244 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

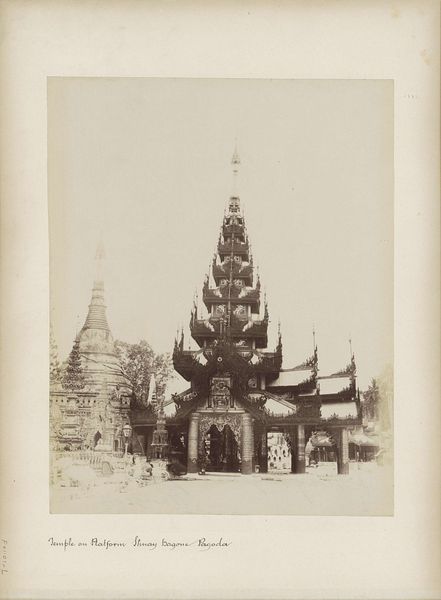

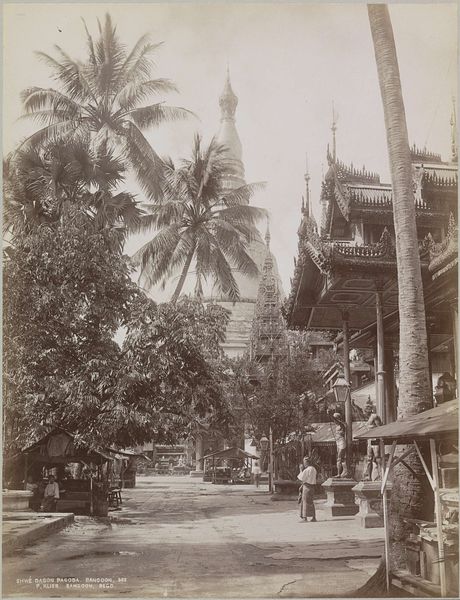

Curator: This is a photograph titled "Ingang van de Shwedagon pagode, Rangoon" attributed to P. Klier, and its dating is estimated between 1895 and 1915. The image captures the entrance of the Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon. Editor: My immediate impression is one of meticulous craftsmanship and serenity. The intricate detailing of the pagoda’s architecture, set against the open space, creates a contemplative atmosphere. Curator: Indeed. Looking closely, the photographic process itself is fascinating. Consider the material reality: glass plate negatives, the specific chemical emulsions of the time. Each element in this image’s creation required specialized labor and techniques. And of course, the infrastructure for both artistic creation and mass consumption. Editor: Absolutely, and we must consider the historical and political dimensions too. This pagoda serves as more than just a picturesque subject. Its construction involved hierarchies of labor that continue to shape identity and lived experiences in Myanmar, including but not limited to, the colonial presence and power dynamics implicit in the photographer’s gaze. Curator: How so? I see the work, but colonial structures are less immediately available. Editor: By depicting this sacred space for a presumably Western audience, Klier’s photography subtly reinforced the colonial narrative. It is both documentation and a form of appropriation. Who held the power to represent whom, and how? The answer echoes beyond this simple photo. It resonates deeply. Curator: I think we are well advised to recall how the development of photographic technology in general coincides with colonialism, allowing images and understandings to move freely between colonized countries. What are the ethics of visual documentation during periods of colonial oppression? Editor: Precisely. We need to view this photograph not just as an artistic piece, but as a historical artifact, embedded with social, cultural, and political implications. Considering, as well, the way Buddhist identity is formed with reference to it, too. Curator: I appreciate that critical framing. Considering this, I walk away feeling like I now possess a deeper awareness of how photography intersects with labor, social, cultural, and colonial power. Editor: Me too. Now, with increased sensitivity, I am reminded that this work holds multiple histories in plain sight.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.