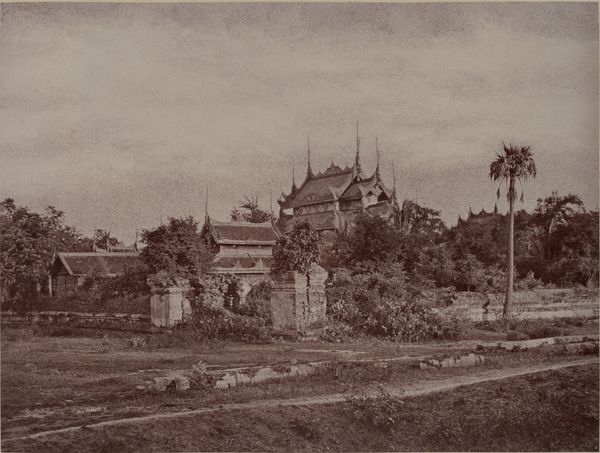

photography, albumen-print, architecture

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

albumen-print

#

architecture

Dimensions: image: 25.7 × 34.8 cm (10 1/8 × 13 11/16 in.) mount: 45.6 × 58.5 cm (17 15/16 × 23 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This is Linnaeus Tripe's albumen print, "Amerapoora: Mygabhoodee-tee Kyoung from East," taken around 1855. Editor: My first impression is a dreamlike stillness. It feels hushed, the sepia tones adding to a sense of faded grandeur. It is almost as though the temple has been forgotten by time. Curator: Absolutely. Tripe's work during this period is particularly interesting when contextualized within the history of British colonialism and visual representation of other cultures. The careful staging and technical mastery of albumen printing provided the British with specific ways of documenting, framing, and indeed, possessing this region visually. The temple represents the Burmese culture that, at the time, existed as the other of Europe. Editor: That makes perfect sense. There’s this almost unsettling tranquility about it, a sense of imposing stillness, especially in how he captured the detail of the building itself and its layered roofs with those very, very sharp lines contrasting with the dreamy trees almost hazing into each other in the back. It looks sturdy, as though made for defense, a way to project power from afar in a foreign place. I wonder what was going through his mind. Curator: Tripe worked as a photographer for the British East India Company, so that intersectional power dynamic you point out, how architectural grandeur becomes an exercise of authority, would have been unavoidable, or perhaps even promoted. It really shows us how photography functioned as an active participant in constructing perceptions of colonial subjects, framing and exoticizing landscapes to serve very particular ideologies. Editor: Knowing that shifts the entire feel of it. I think I came in seeing romance, but now it almost feels calculated, even cold. Art can change when our perception of reality is changed through new contexts. This also suggests something bigger: power relations can literally define vision in unexpected ways. Curator: Precisely, and I think this speaks volumes about our roles as viewers. Our responsibility is to critically engage with these works, considering the hands that created them, the power structures at play, and the legacies they perpetuate. Editor: Wow. I'll never see this photograph the same way again. Thank you. Curator: You're very welcome. Understanding that colonial history encourages us to see and acknowledge diverse narratives beyond this pretty, initially calming picture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.