Dimensions: height 206 mm, width 258 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

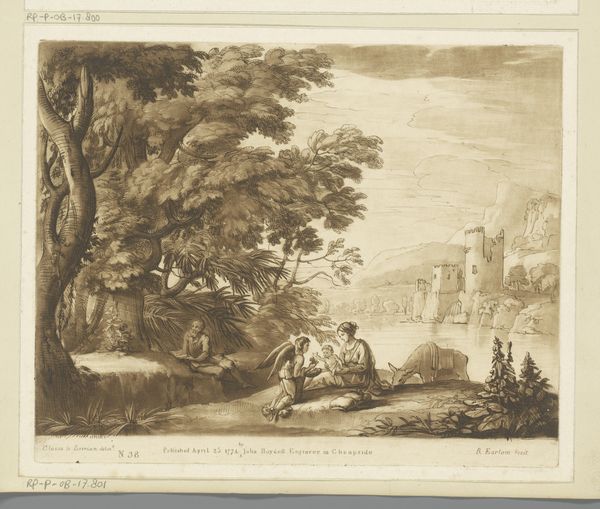

Curator: We are looking at “Landschap met herderspaar en geiten bij een oever," or "Landscape with a shepherd couple and goats by a shore," an etching and engraving made around 1776, after Claude Lorrain and etched by Richard Earlom. The print resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It evokes such a placid, almost melancholy feeling. It's mostly sepia tones which gives the work this subdued feel, with that tranquil river fading into the misty distance. Even the goatherd, she looks completely at ease, as though time simply isn’t of concern to her. Curator: Earlom's choice of sepia undoubtedly draws from the tradition of idealized pastoral scenes that were incredibly popular, designed to recall a simpler, more innocent time, echoing classical antiquity. Editor: Right, but how much of this 'simplicity' is constructed? We're not really seeing a truthful depiction of peasant life. Look closer and we begin to see it really romanticizes agrarian labor while it neatly erases any kind of material difficulties those peasants actually would've been going through in that century. Curator: Well, perhaps. But such artistic license underscores the human desire to find harmony and connection to the earth, doesn’t it? This scene taps into very old archetypes: the shepherd as a guardian, a protector. The goats too have appeared in art and literature as symbols of both vitality and sacrifice. Editor: I agree, but it also conveniently supports the prevailing social order, this idea of contentment with one's lot, reinforcing existing class structures. Who do idyllic landscapes really benefit? Curator: You raise a good point about whose voices we prioritize and about access. The beauty of it remains though, wouldn’t you agree? As humans we seek to emulate such balance through art, perhaps reaching towards utopia if only in visual terms? Editor: It serves as a striking reminder of how aesthetics and ideology are so closely entangled, and it forces us to ask, what can we really appreciate given the complex history? I guess it begins by questioning the visual vocabulary itself, as you suggest. Curator: Ultimately this engraving invites conversation. What meanings, values, and desires are evoked across generations? It remains open.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.