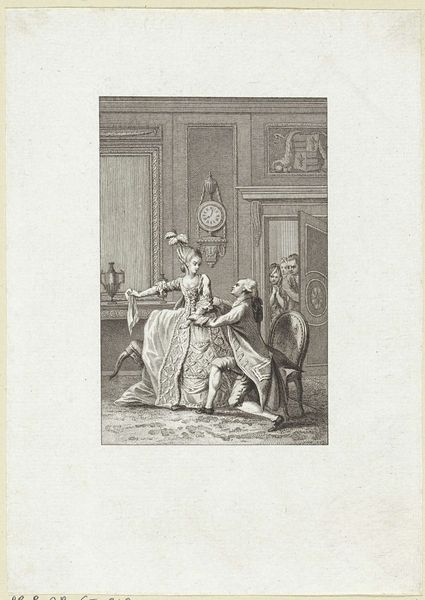

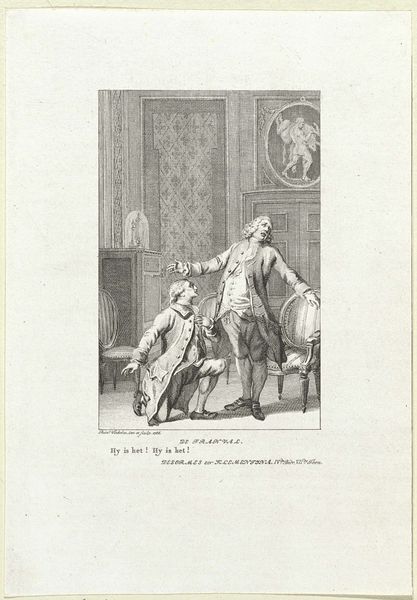

intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

intaglio

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

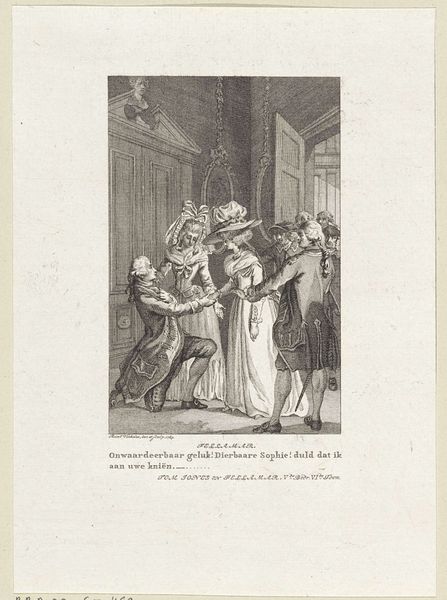

Dimensions: height 212 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

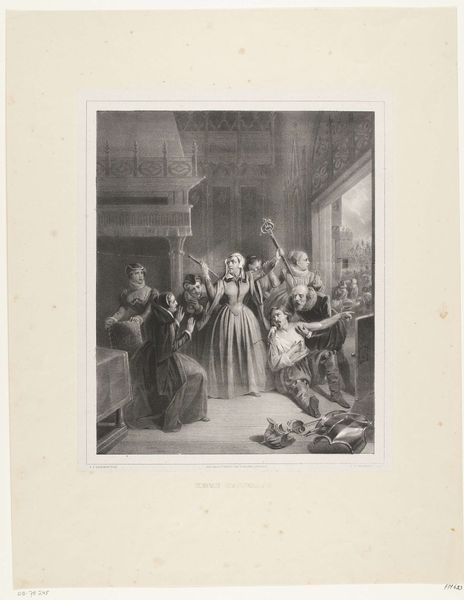

Editor: This is "Ruzie in een vertrek" from 1794, by Reinier Vinkeles. It’s an engraving, so an intaglio print. It feels theatrical, almost staged. What catches your eye in this depiction? Curator: Well, let's consider the engraving process itself. Look at the precision of the lines, the labor involved in creating this scene not through expressive brushstrokes, but meticulous, repetitive cuts. Doesn't that immediately bring up questions about the purpose of such craft? Is it simply to illustrate a "quarrel," or something more? Editor: That's true, it must have taken ages! I was so focused on the scene, I didn’t really think about the process. It almost feels like mass-produced art because it is an engraving. Curator: Precisely. Consider the target audience: who had access to such prints? This wasn't "high art" for the aristocracy; this was reproducible, portable, meant for a wider, likely middle-class consumption. Now, how does that change how we understand the image? Is this ‘genre painting’ about entertainment, or something else? Editor: Good point. It becomes almost like a commentary on domestic life accessible to more than just the upper class. Curator: Exactly. The "ruzie" – the quarrel – it's a commodity in itself. What are people consuming here: a morality tale, entertainment, or something else? It’s about class awareness and dissemination. Editor: I never thought about art in that context. Looking at art this way really opens up how the materials and the way the artwork was produced influence the reading of its subject! Curator: And that's precisely the value of a materialist approach – shifting focus from a singular interpretation to a multi-faceted understanding of process and dissemination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.