drawing, graphic-art, print, paper

#

drawing

#

graphic-art

# print

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

line

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: Overall: 7 13/16 x 6 3/16 x 3/8 in. (19.8 x 15.7 x 1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

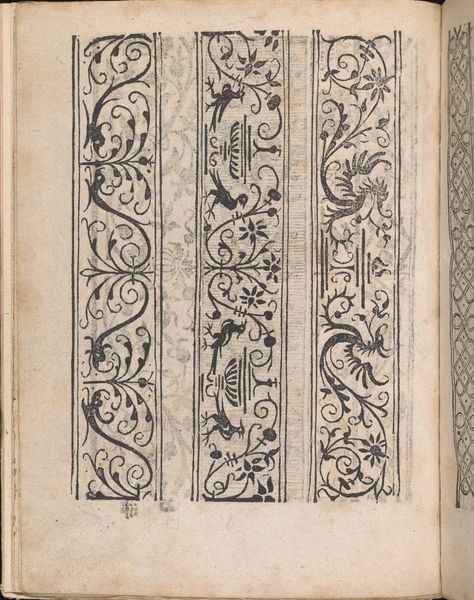

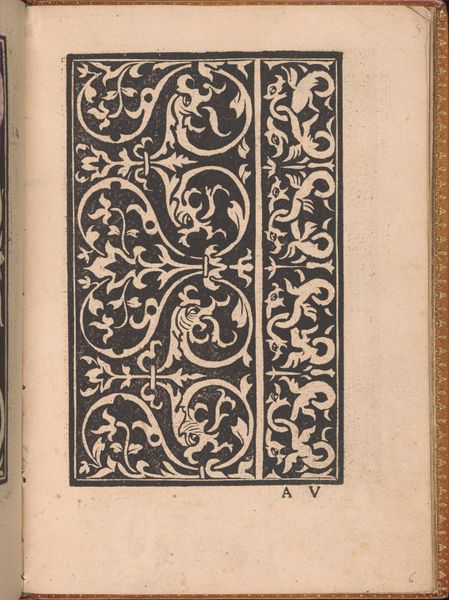

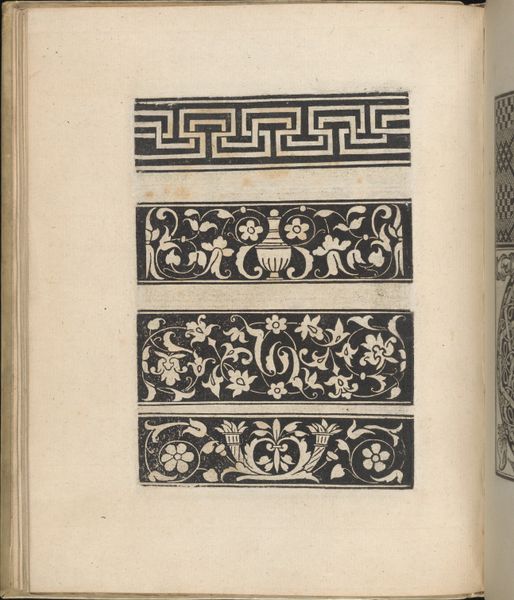

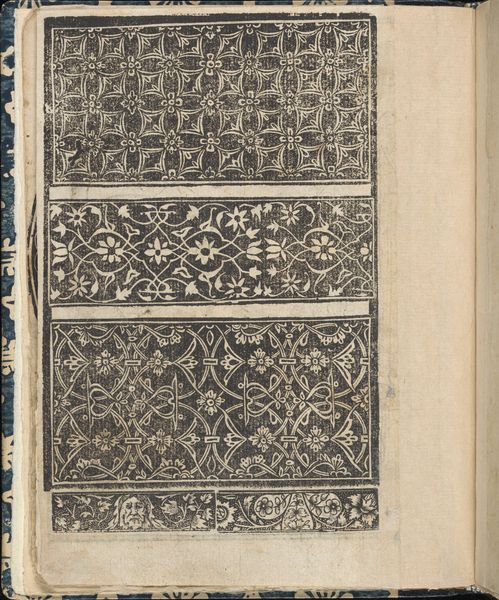

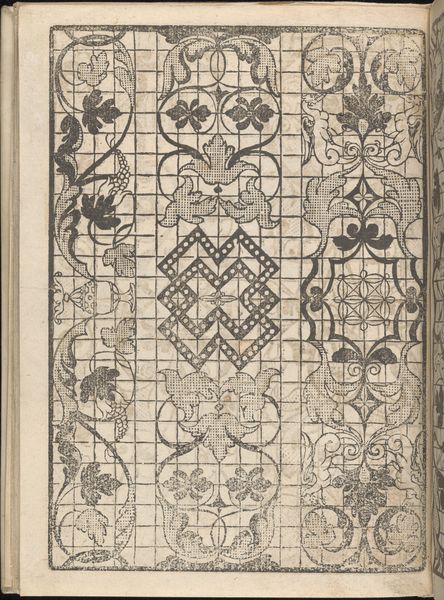

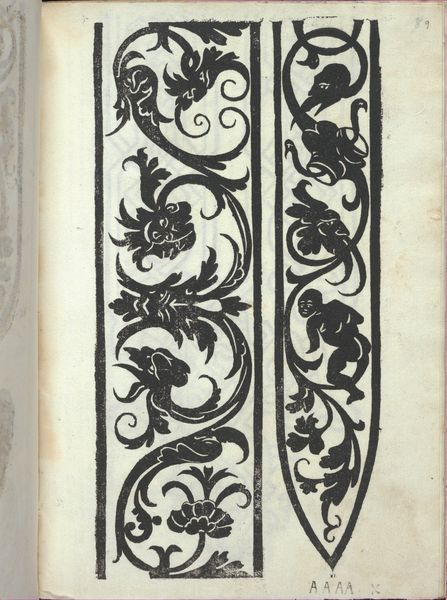

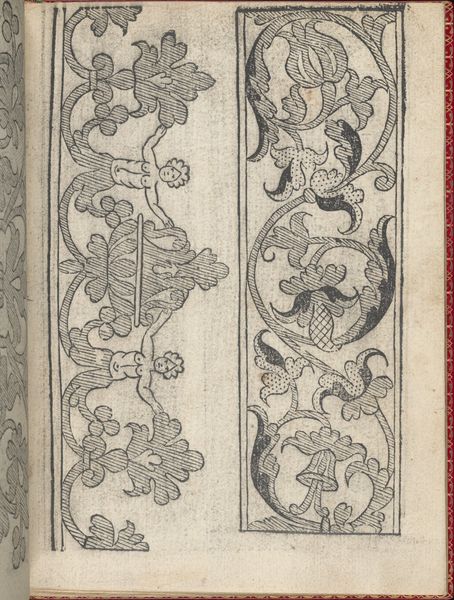

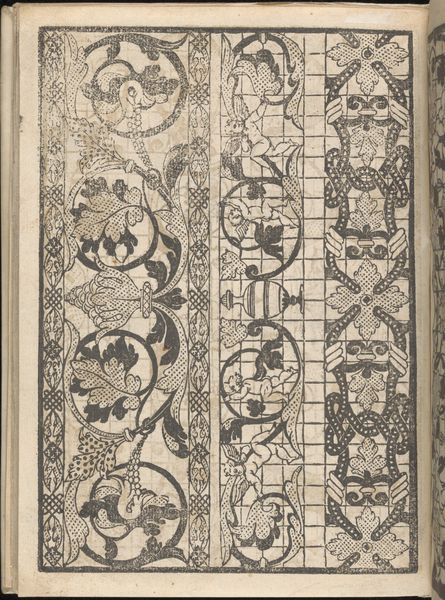

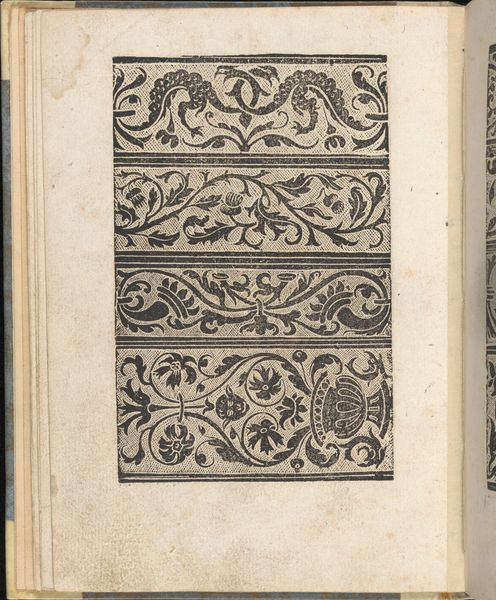

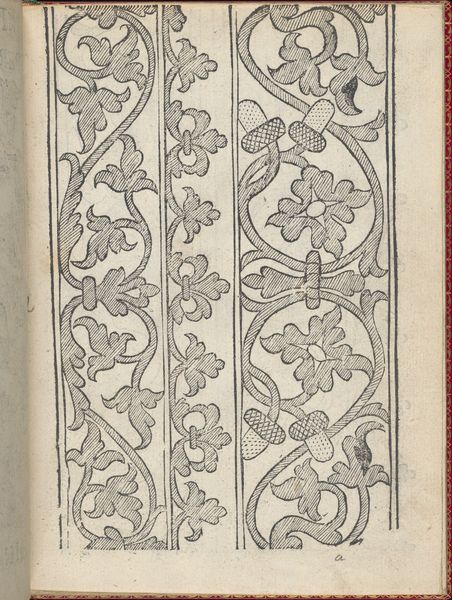

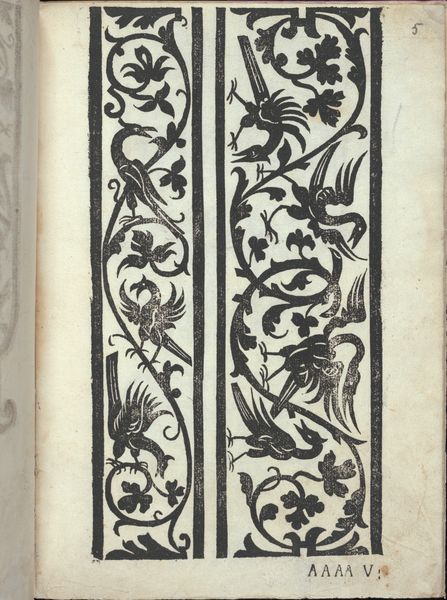

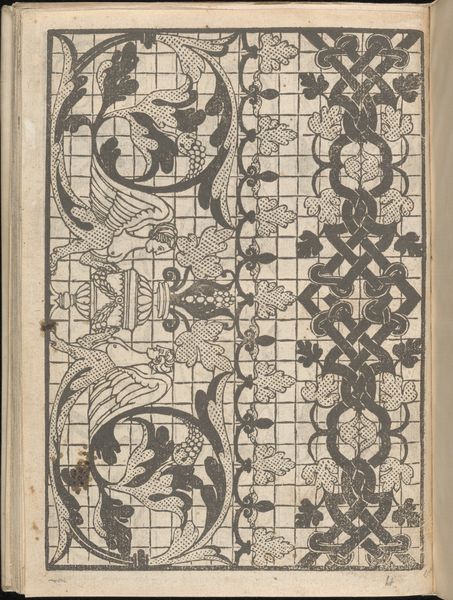

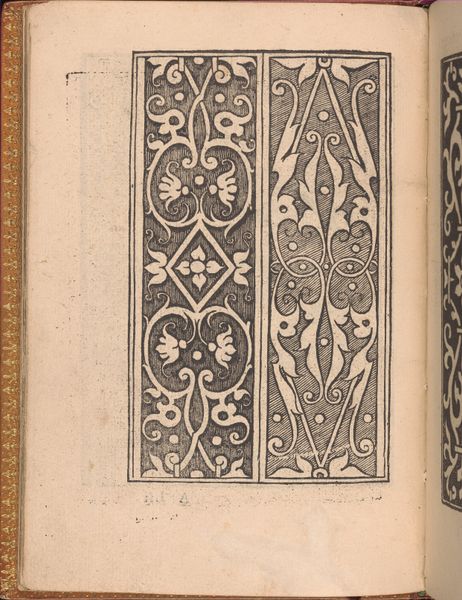

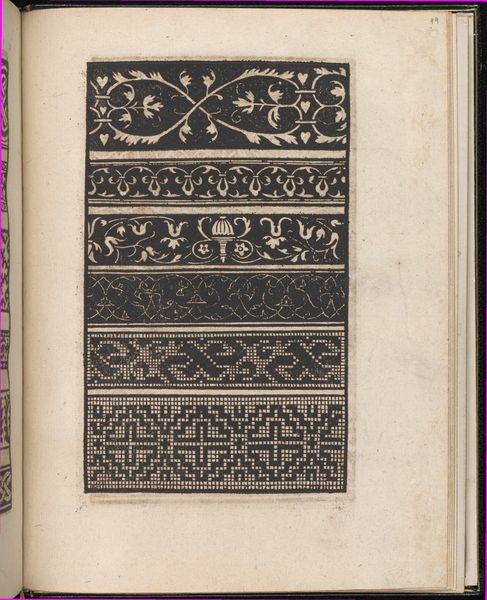

Curator: Look at this page from Giovanni Antonio Tagliente's "Essempio di recammi," printed in 1530. It’s a stunning example of Renaissance printmaking, housed right here at the Met. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the regimented patterns and their graphic quality, it feels quite intense given that it's black on white. Almost like a codified language. Curator: Exactly! It is. These aren't just decorations; they’re instructions. "Essempio di recammi" translates to "Examples of Embroidery." This book was essentially a pattern book, providing designs for embroiderers. It gives us insight into 16th-century textile arts and popular aesthetics. Editor: So, these designs are meant to be translated onto fabric. Knowing that changes how I perceive the patterns, giving them another layer of meaning, and imagining what other purposes they may have served beyond surface appeal. Did the circulation of print, enabling the reproduction of designs like these, democratize fashion and aesthetics in some way? Curator: That's precisely what is so revolutionary here! The printing press democratized design. These patterns were no longer limited to the wealthy who could afford to commission unique designs. It fostered broader participation in crafting culture, expanding across society the means of expressing visual status, style, and, yes, political position. The symbolic power is enormous. Look at the use of classical motifs, a maze and urns. What would those patterns have signified to the original artisans and viewers? Editor: True, and the visual motifs here act almost like cultural memory triggers. These familiar, timeless designs weave together associations, but they do invite reflection on changing meanings. A classical maze, in antiquity, might symbolize the twists of fate; in the Renaissance, perhaps, the search for humanist knowledge? Curator: Perhaps it mirrors the increasingly elaborate societal mazes? Its publication must have had some cultural implications. Editor: It makes you consider the role these printmaking designs had for visual instruction. Each pattern is laid out like an exercise. There's such clarity to it. I wonder, did embroiderers have free reign on adapting these examples, or was there cultural capital in accurately executing each motif? Curator: It offers a peek into the everyday life and craftsmanship of the period. Imagine the hands that meticulously recreated these designs with needle and thread! Editor: Yes! It is also a reminder that images can operate simultaneously on practical and intellectual levels, informing everyday labor and spurring ideological questions about fashion, style, and access to visual vocabularies of design and symbolism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.