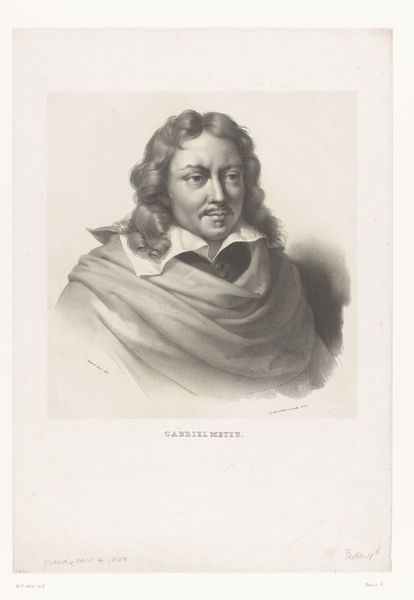

drawing, print, charcoal, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 333 mm, width 249 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

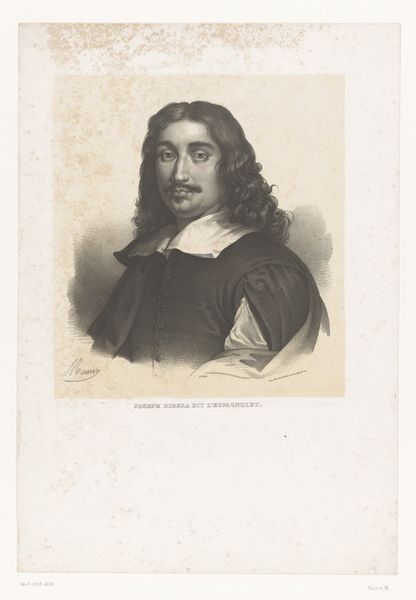

Curator: Here we have Nicolas Maurin's "Portret van Karel du Jardin," likely rendered sometime between 1826 and 1852. It appears to be a print, made with charcoal and engraving techniques. The portrait presents its subject, presumably Karel du Jardin, from the chest up. What's your initial read on this piece? Editor: It strikes me as a very introspective portrait. The lighting is soft, almost reverential, casting a gentle shadow that makes du Jardin seem deep in thought. There is a melancholic feel that draws the eye. Curator: I agree; this image aligns with the Romantic movement's focus on emotion and individual experience. Maurin, although a successful portraitist, produced images within specific societal parameters and artistic traditions. The goal was often less about revealing individual psychological depth, and more about adhering to an established visual vocabulary that signaled status and artistic prowess. Editor: Yet the way his hands are clasped—almost protectively—and his slightly downcast eyes, hint at something more personal, doesn’t it? Hands often carry powerful meaning in portraiture. What do they tell us here, combined with the costume of wealth, such as the puffed shirt sleeves, black and gold sash, and flowing dark curls? Curator: Absolutely, the details communicate volumes! While artists were somewhat constrained, subtle choices could reveal or perhaps even invent aspects of the subject's persona. His hands and gaze suggest perhaps sensitivity beneath the finery. But this could be as much a construct of the artist or, more intriguingly, the sitter, as an actual insight. This "Karel du Jardin" holds significance less for definitively revealing the man himself, and more for encapsulating 19th-century portrait conventions. Editor: And perhaps this contributes to the enduring appeal of portraits? They speak not only of their subject but also of the artistic and cultural landscape that birthed them, with each symbol imbuing more significance over time. The mustache alone! It speaks of class, culture, masculinity, power, wealth… Curator: Exactly! Portraits become cultural artifacts, laden with ever more historical meaning over time. In essence, we view a layering of perceptions: the artist's, the subject's, and our own, refracted through history. Editor: It is an amazing blend of what's known, and what's inferred. Something to think about next time you look at the past in a museum setting. Curator: Precisely, art functions as a societal mirror, reflecting both who we are and who we aspire to be.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.