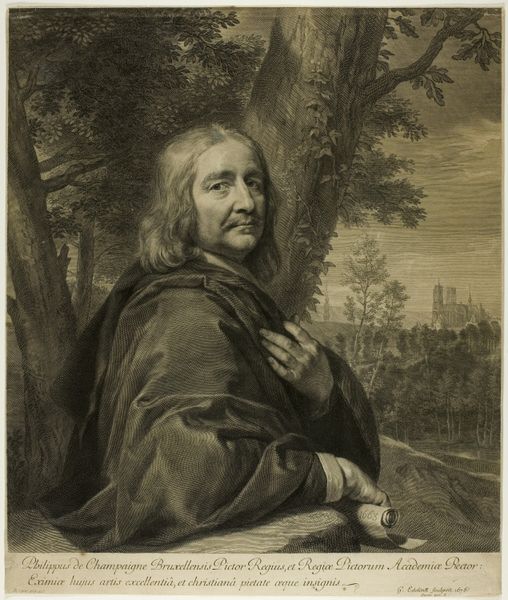

Dimensions: height 287 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

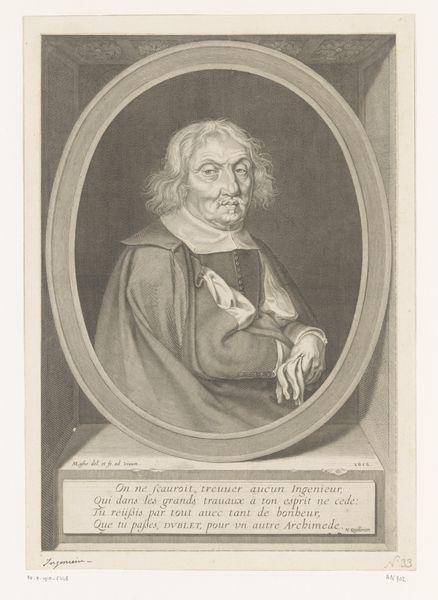

Curator: This is a 19th-century engraving, "Portret van Philippe de Champaigne," crafted by C.J. Nördlinger. The portrait, evocative of the baroque and realist traditions, depicts the 17th-century painter Philippe de Champaigne himself. Editor: Oh, wow. He’s got this…melancholy in his eyes, almost pleading, yet also incredibly self-assured. The way his hand is positioned...it's theatrical, like he's about to deliver a line. There’s an intensity that grabs you. Curator: The original Philippe de Champaigne was, of course, a significant figure in the French Baroque. Focusing largely on portraiture and religious scenes. We can see Nördlinger channeling some of that intensity—albeit with a 19th-century lens. I'm struck by the ways in which representations of individuals are changed through time and mediated through various artistic practices like engravings which, for a time, were a method of disseminating imagery, mostly to the elites. Editor: Absolutely! And there's this kind of subtle tension...He’s draped in this dark cloak but, somehow, doesn't fade into the background. I'm guessing it’s due to how the artist used hatching. Curator: Exactly. Hatching, the density and direction of the lines, create tonal variation that provides dimension. The way Nördlinger used it really speaks to the circulation and replication of images—before the invention of the photograph and other widespread technologies. It provided wider social visibility and accessibility, especially for people like Champaigne. But this also reflects ideas about status, class, and identity that get perpetuated and solidified over time. Editor: Thinking of reproductions, that cloak seems to fade into the background. Kind of makes him immortal through its presence. A reminder he has something to say, beyond the grave...And look at how those stray hairs are engraved, all of that care placed on rendering him as real as possible. Curator: Yes. Engravings also helped to cement these very romantic notions of artistic genius through generations—an effect that continues into modernity. Editor: So true. It's amazing how an image, even one of someone who lived centuries ago, can trigger so many ideas. It’s almost like Champaigne is still with us. Curator: Indeed, and in that way the image and Nördlinger live on, and we are also now apart of that history as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.