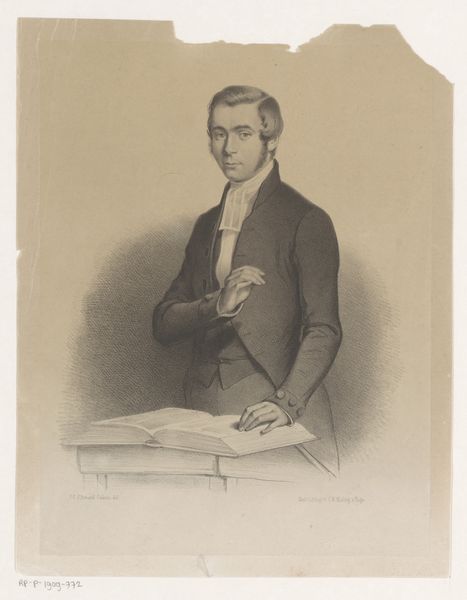

Dimensions: height 574 mm, width 414 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

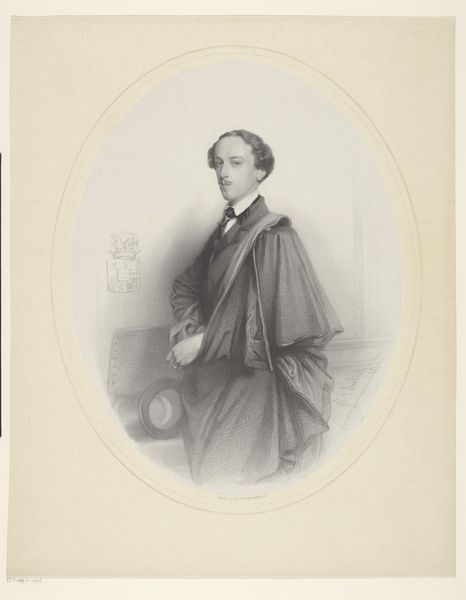

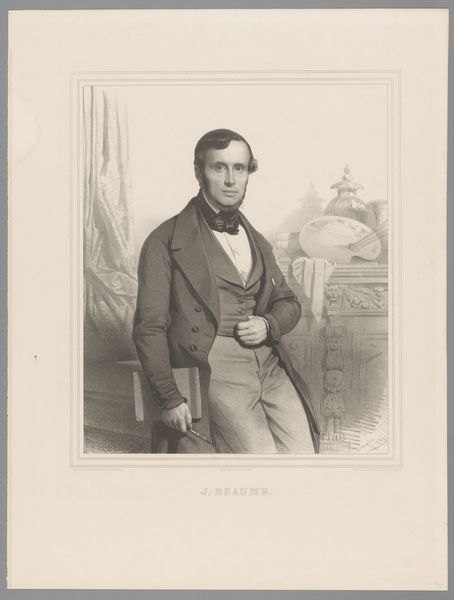

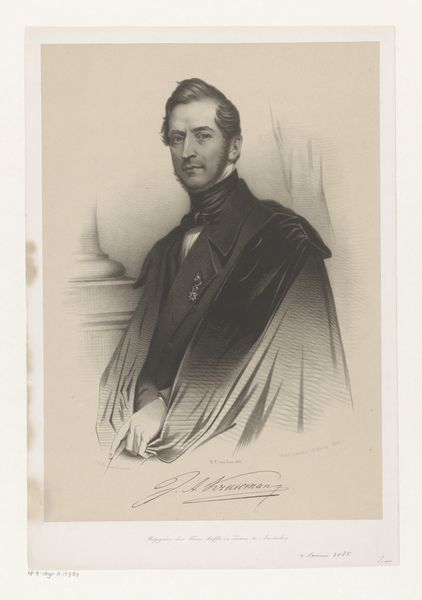

Editor: So, this is *Portret van Emile de Jaer*, an engraving from 1855 by Joseph Schubert, housed at the Rijksmuseum. It’s quite formal; de Jaer has a very serious expression, and the column hints at classical authority. What social context informed this kind of portraiture? Curator: It's fascinating to consider these commissioned portraits as potent symbols within a very specific, and structured, societal landscape. This image communicates a desired status. Consider the materiality – an engraving, a readily reproducible medium. What does that choice say about the intended audience and the spread of de Jaer's image? Editor: That's interesting, it feels more like an announcement than something deeply personal. Would a painting on canvas convey something different at that time? Curator: Precisely. An oil painting signified considerable wealth, signaling exclusivity and artistic patronage. An engraving, however, makes de Jaer’s image far more accessible. Think about who could afford to commission or purchase a painting versus an engraving. What rising class might this medium be aimed toward? Editor: Perhaps the emerging middle class wanted to emulate the aristocratic tradition of portraiture, but in a more affordable way. Did that impact how artists represented their subjects? Curator: Definitely! The style begins to shift to realism, mirroring a growing cultural value of the bourgeoisie and their achievements. Also consider, beyond affordability, how does printing an image relate to political messaging? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way, so making and sharing engravings would have allowed politicians and other prominent people to share propaganda. That's amazing. Curator: Exactly! So it is important to read artwork within these cultural and societal structures that define it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.