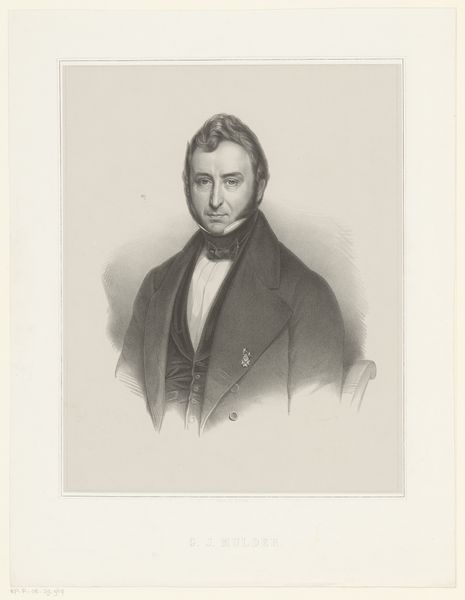

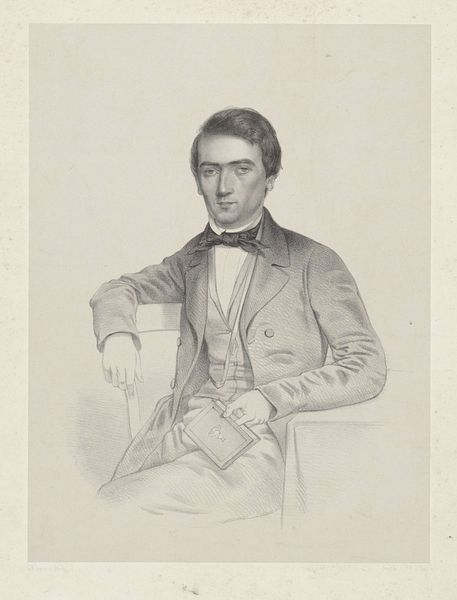

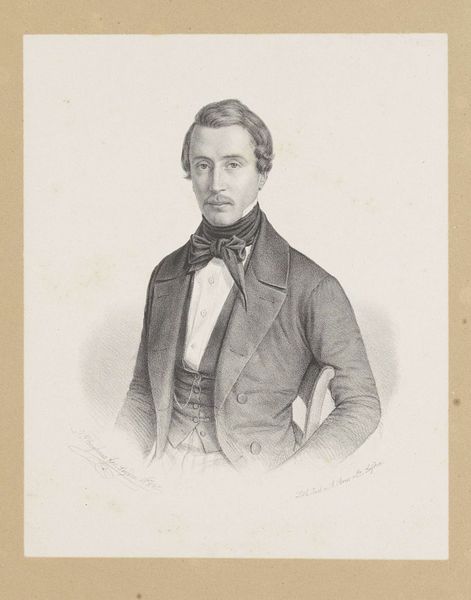

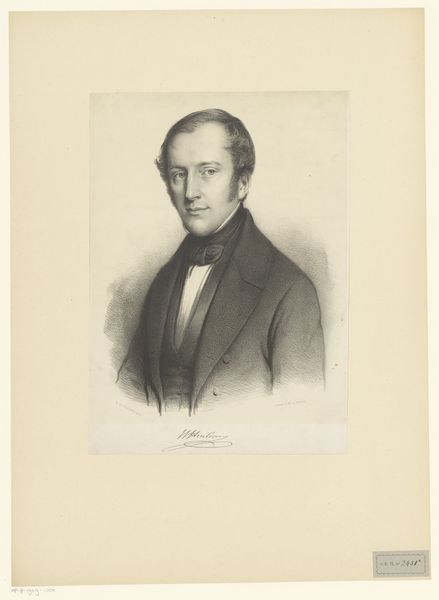

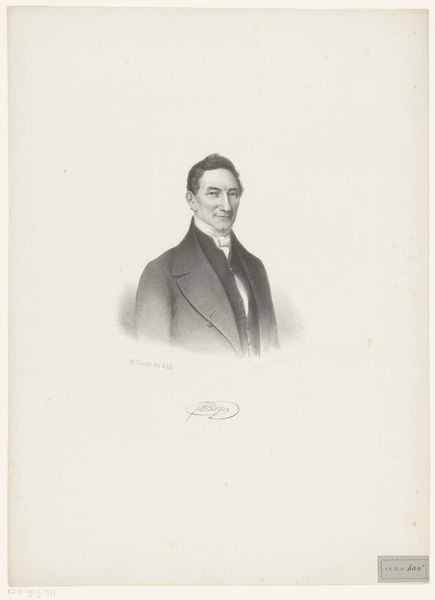

drawing, pencil

#

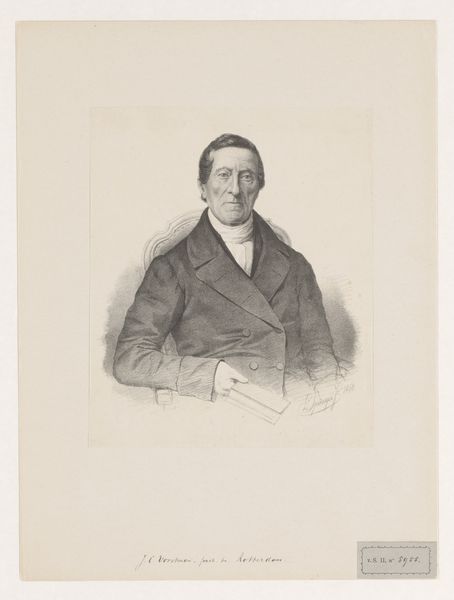

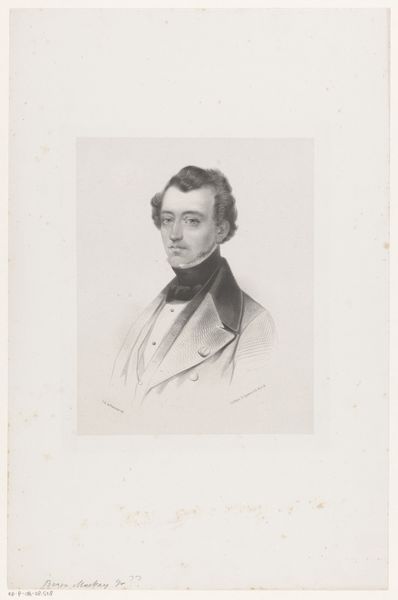

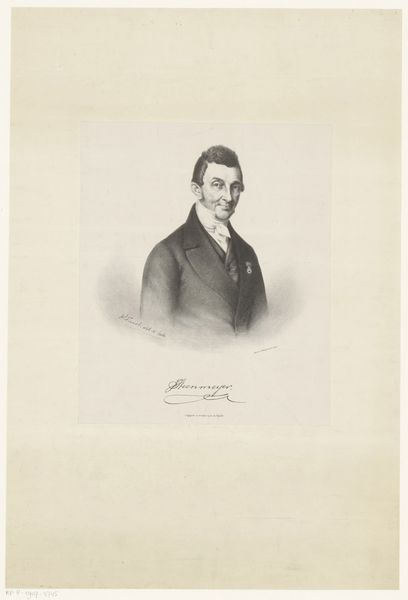

portrait

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

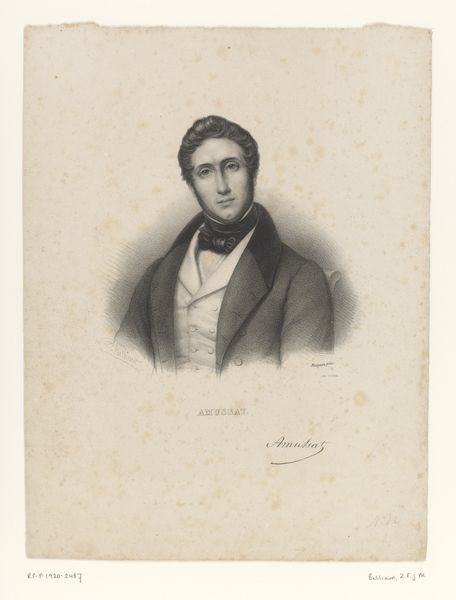

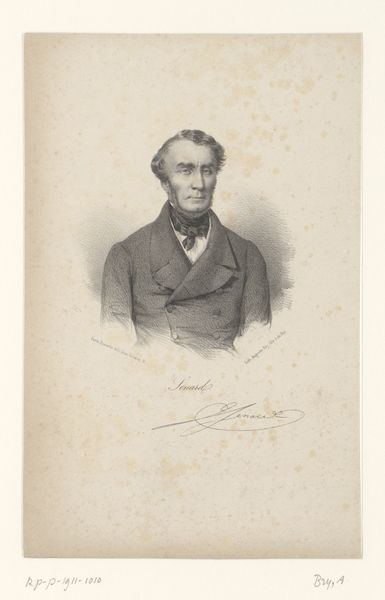

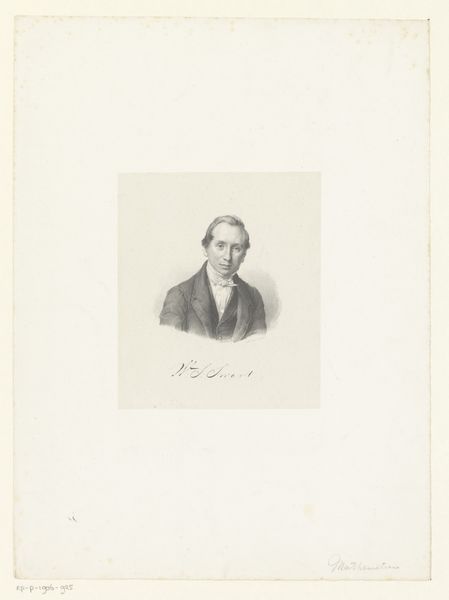

old engraving style

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 375 mm, width 260 mm, height 485 mm, width 355 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It’s the pencil work that first strikes me—remarkably detailed and delicate for such a formal portrait. Editor: Indeed. What we're observing here is a pencil drawing from somewhere between 1842 and 1880, titled "Portret van N.J. Hofmeyr." It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Let’s delve into its significance. My first thought is the stark composition reflects the growing role of individual portraits celebrating the burgeoning merchant classes and figures rising in social standing and influence during this time. Curator: It’s interesting you immediately consider the commercial class. I see it as a deeply intimate depiction. Hofmeyr’s pose, hand placed delicately on his chest, speaks to a controlled presentation of self, yet there's also an element of vulnerability there, the almost understated pride reflecting the values and aspirations of a specific social class amidst a period of intense social transformation. The subtle, almost whispered draftsmanship mirrors the evolving notions of bourgeois masculinity. Editor: I understand the sensitivity you point out, but I am also struck by the economic realities of portraiture during this period. Think of the materials: pencil, paper, the labour-intensive act of drawing itself. Each element carries weight within a broader context of production and consumption. Did this commission serve the artist's or patron’s social ambition and to what extent could the material process allow a challenge the established power structures that commissioned such likeness? Curator: That's a crucial consideration. However, let's also consider how Hofmeyr's own identity might intersect with these societal forces. Was he an advocate for or an oppressor in the racial politics of his time? How did his representation reinforce or challenge the power dynamics? We must bring in a multi-dimensional, critical theory lens. Editor: I concede that examining those dynamics of representation is crucial. How did the creation and exhibition of this portrait support colonialist aims or class distinctions? Examining the social life of the work, from artist’s hand to museum wall can open those insights and interpretations. Curator: Exactly. It pushes us to see beyond the surface of the portrait and ask about whose histories and realities are privileged and whose are being suppressed. Editor: So we both land on it offering layers of reflection of artistic labour and material practices in concert with social dynamics reflected and contested through such acts. Curator: A productive intersection, revealing not only the artist’s skill, but also a critical and socially engaged lens to reveal this individual in the wider context of production, class, and ideology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.