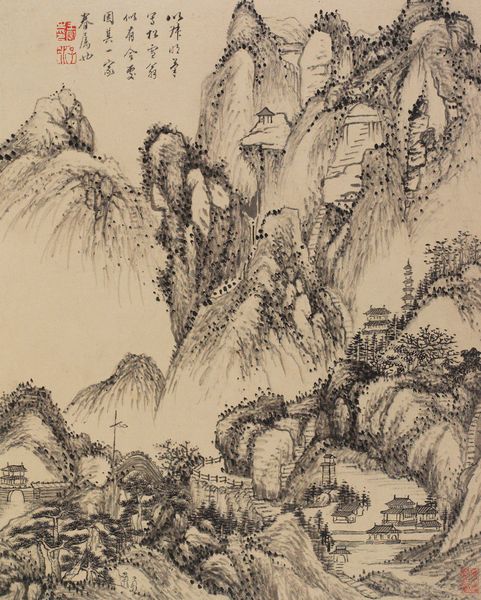

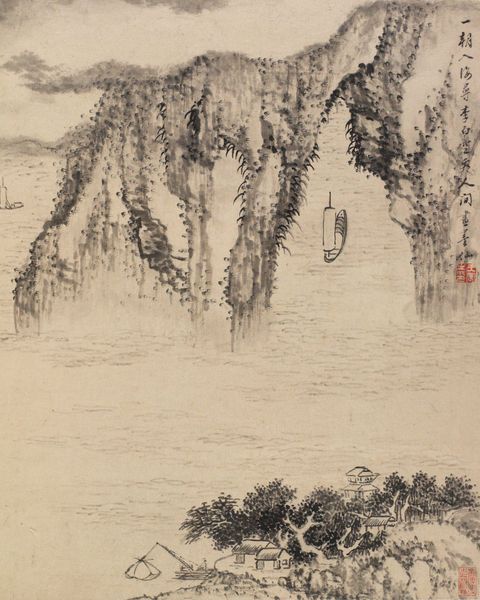

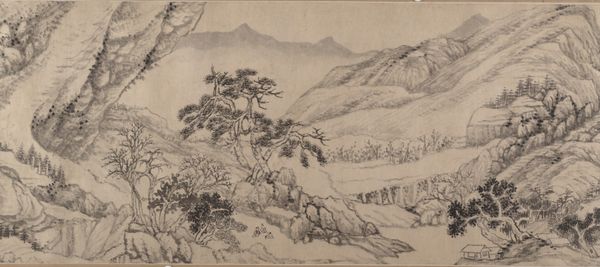

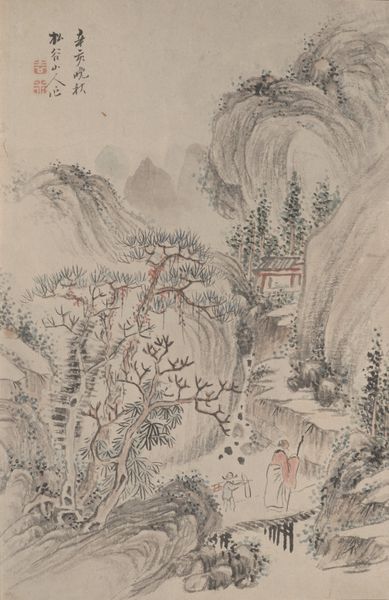

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

22_ming-dynasty-1368-1644

#

ink

#

mountain

#

china

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: Image: 11 in. x 10 ft. 6 in. (27.9 x 320 cm) Overall with mounting: 12 1/4 in. x 34 ft. 2 3/4 in. (31.1 x 1043.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

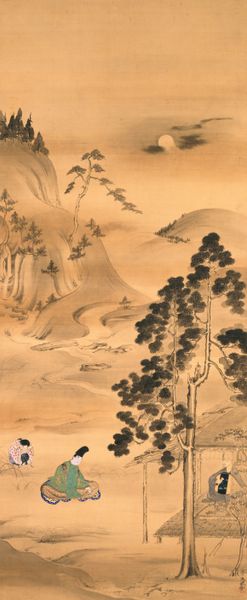

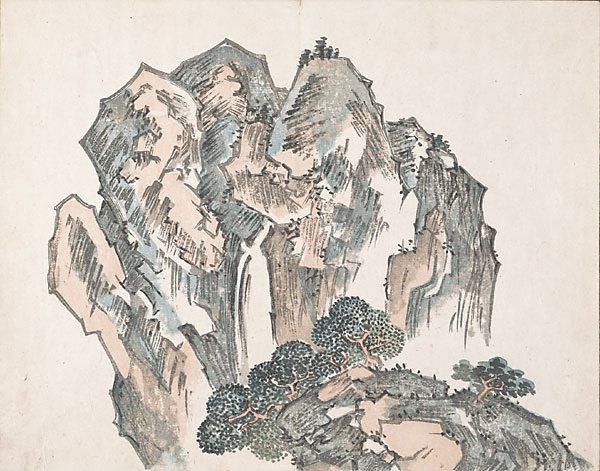

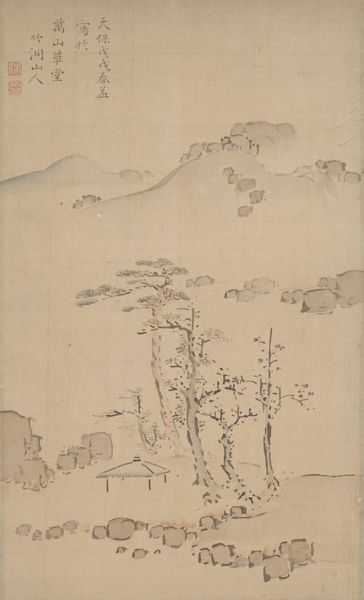

Curator: Looking at this landscape, I’m immediately struck by its somber yet powerful atmosphere. There's a feeling of solitary grandeur, wouldn't you agree? Editor: It certainly evokes a sense of monumental scale, rendered with what looks like deft strokes of ink wash. Shall we delve a bit deeper? This is “Illustration of Su Shi’s ‘Second Ode on Red Cliff’” by Zhang Ruitu, created in 1628, during the Ming Dynasty. It is currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curator: Tell me more about Zhang Ruitu's approach and the cultural context informing this artwork. The landscape feels so sparse, almost post-apocalyptic. Editor: Ruitu’s ink drawing is steeped in the philosophy of its era. The very materials -- the ink, the paper -- point to a long tradition of literati painting. This wasn't about representational accuracy. Instead, it was concerned with conveying the spirit, the essence of the landscape through the brush. Curator: And "the spirit" is intrinsically tied to the politics of the time, I would argue. Ruitu was a controversial figure later in his career, heavily implicated in factional strife within the Ming court. Considering that Su Shi himself was a figure in exile, his words likely carried specific resonances during the late Ming period. Editor: Absolutely. But even at a fundamental level, the materiality speaks to that political reality. Access to quality ink and paper, the very act of creating art, were themselves embedded within complex systems of patronage, power, and the scholar-official class. How materials were commissioned, produced and valued. This wasn't an accessible art form, either for making or possessing. Curator: So, the mountains and the seemingly simple hut aren't merely scenic, but they are stand-ins for larger social concerns: philosophical allegiances and the artist's response to courtly life, the precarity of political fortunes. There's also that tension between retreat and responsibility embodied in the lone figure. Editor: Indeed. Understanding the work involved understanding the labor involved in that production and how those networks touched not only artistic style, but social ones too. Curator: Reflecting on the work then, I find myself pondering about our relationships to social responsibilities in light of history. The individual experience amidst greater historical upheaval continues to fascinate. Editor: For me, I appreciate a greater awareness of how simple acts such as ink drawing, and a person's engagement with landscapes in art-making, have social underpinnings with reverberations even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.