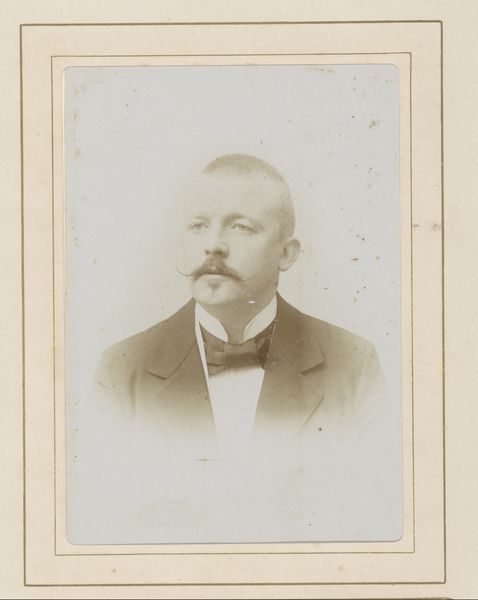

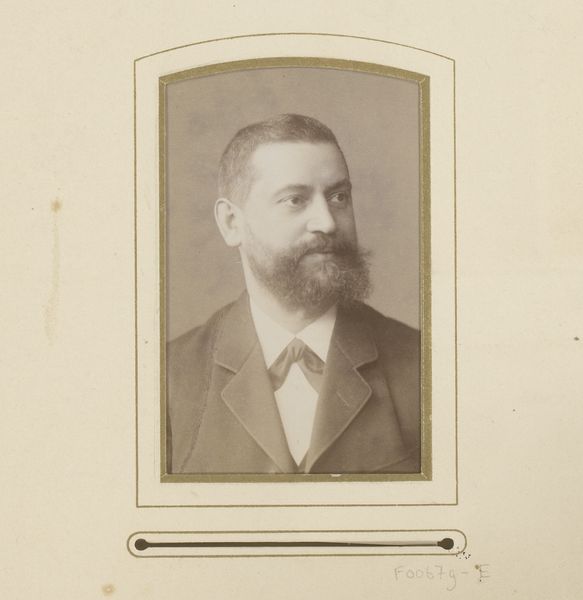

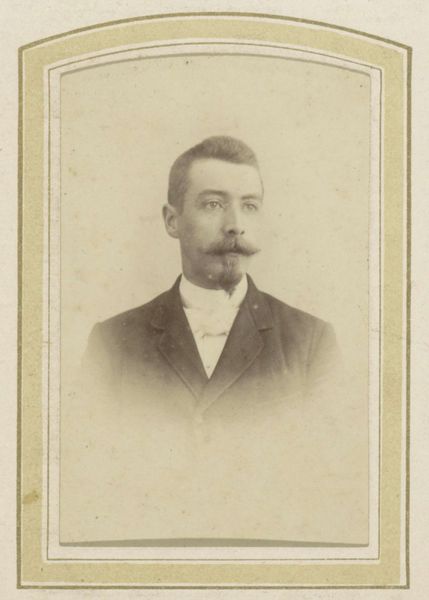

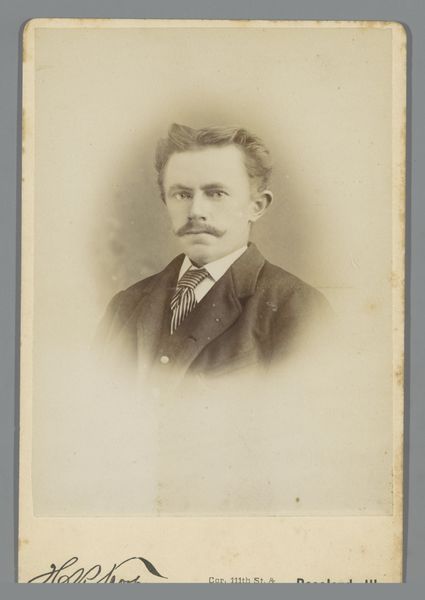

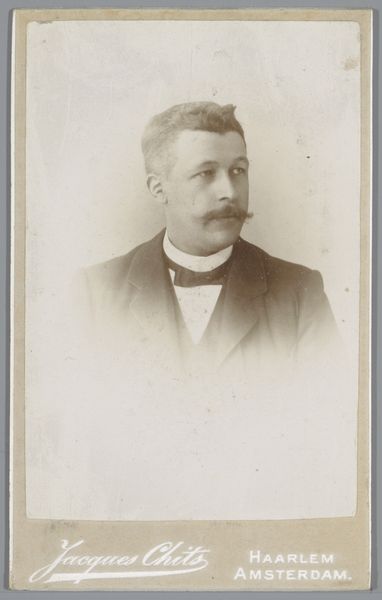

daguerreotype, photography

portrait

daguerreotype

photography

portrait art

realism

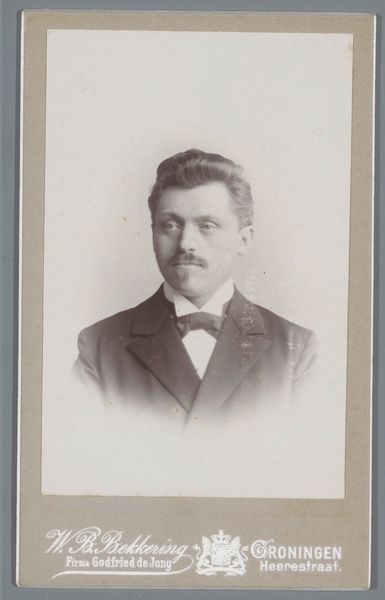

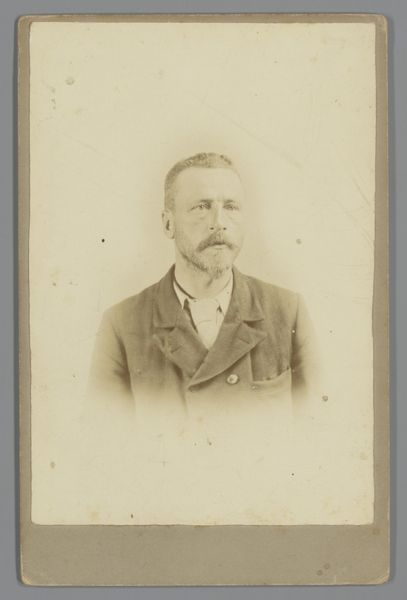

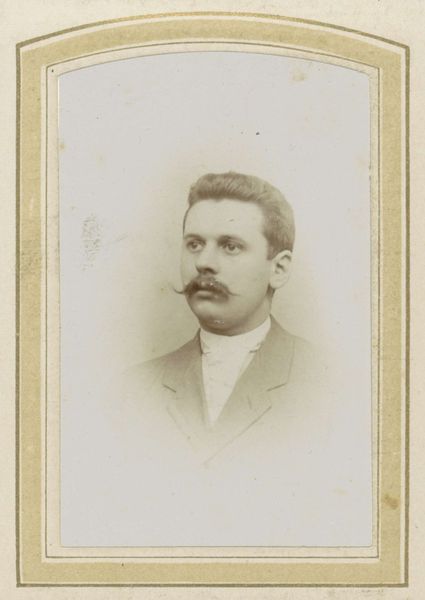

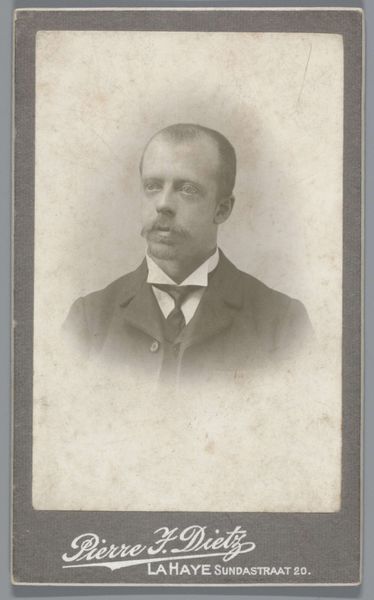

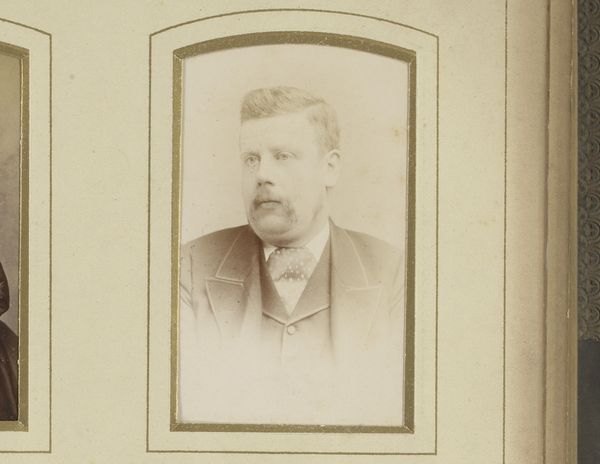

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 58 mm, height 103 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a daguerreotype, "Portret van een man met een baard en een das," or "Portrait of a man with a beard and a tie," made sometime between 1866 and 1900 by Johan Christiaan Reesinck. I'm immediately struck by the starkness and the intense detail, despite the faded look of the image. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: Well, let’s think about this object as a manufactured item. The creation of a daguerreotype was a complex process, involving specific chemical preparations on silver-plated copper. Think about the labour involved. How readily available were the resources needed? How might the expense impact the types of people who sat for such portraits? Editor: That’s interesting! So, you're suggesting we look at this beyond just the image itself, to think about the actual materials used? Curator: Exactly. The materiality of early photography profoundly shaped its role in society. The daguerreotype was, in its time, both a scientific marvel and a commodity. Consider the sitter's suit, the carefully chosen tie, details rendered meticulously by this new technology. The cost of the materials – the silver, the copper, the chemicals – and the photographer’s skill elevated what could be a mere record into something more...aspirational. It wasn't just about capturing likeness, but projecting a specific social identity. Editor: So the portrait is tied into consumerism and this individual is expressing their material success by having this portrait made. Are you suggesting photography moved art-making away from just painting for the rich and powerful? Curator: It shifted things. The accessibility was still somewhat limited by cost but photography certainly democratized portraiture to a degree, creating new forms of representation and altering older, established hierarchies. Editor: That gives me a whole new way to look at these old portraits, seeing them less as art and more as documents of social and material conditions of the time. Thanks! Curator: Precisely! And by considering these factors, we can truly understand the deeper narratives embedded in what might at first glance seem like just a face from the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.