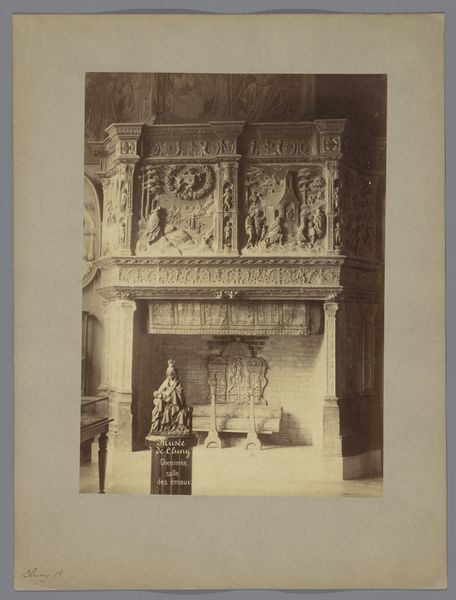

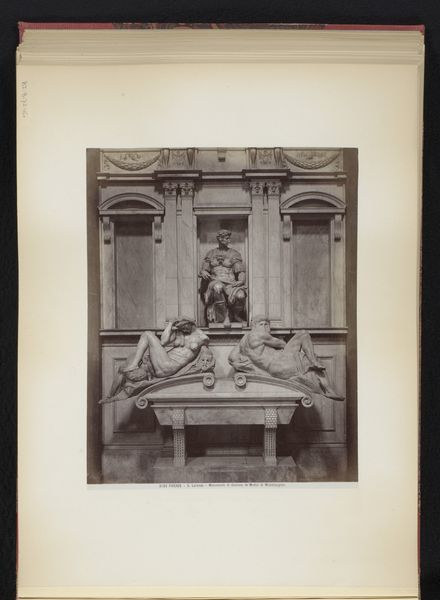

Gipsafgietsel van een schouw in het Musée des monuments français te Parijs c. 1875 - 1900

0:00

0:00

medericmieusement

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 354 mm, width 250 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this photograph, “Gipsafgietsel van een schouw in het Musée des monuments français te Parijs” was taken by Médéric Mieusement, sometime between 1875 and 1900. It's a gelatin silver print of a plaster cast of a mantelpiece. What strikes me is how this image captures not just an object, but an ideal of historical and cultural permanence. What's your perspective on this work? Curator: This image speaks volumes about 19th-century France's relationship with its past, doesn't it? The Musée des Monuments Français was created precisely to preserve and display fragments of architecture and sculpture threatened by revolution and modernization. Photography then plays an important role. Mieusement's photograph, then, isn't simply a document of a mantelpiece. It is about power, class, and the construction of national identity through a selective engagement with history. What do you make of the architectural details and their potential symbolism? Editor: The neoclassical details, the symmetry... it all seems very deliberate, like an attempt to assert order and stability. I'm just wondering who got to decide which monuments were worth preserving and what that says about the values being imposed. Curator: Exactly! The museum and photographs like these presented a very specific, elite-driven narrative of French history. Who was represented in these "monuments," and more importantly, who was conspicuously absent? The selection, preservation, and photographic reproduction were acts of cultural and political affirmation. And for whom? To perpetuate specific cultural dominance by certain ruling classes, but also to educate rising working class regarding values to aspire to? Editor: That really reframes my understanding of what I'm looking at. It's not just an image of a mantelpiece; it's an active participant in a cultural and political dialogue. Thanks, that's really helpful. Curator: And it reminds us that even seemingly neutral acts of documentation can be powerful tools for shaping collective memory and power relations. We are constructing cultural history every time we collect images and artifacts. It's essential to constantly question those narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.