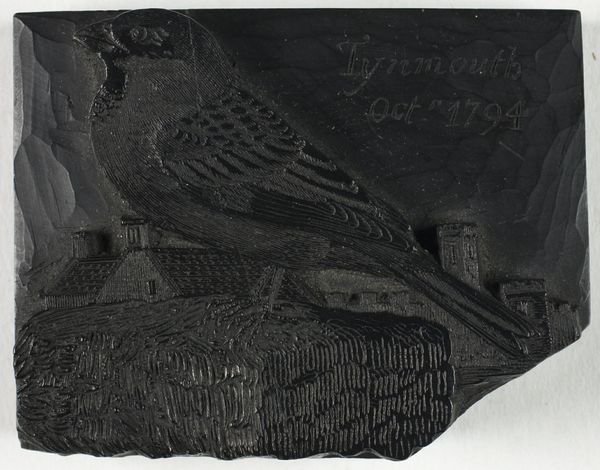

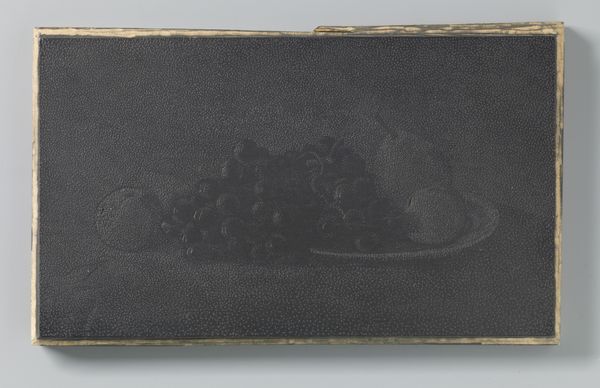

Woodblock for The Swallow, from A History of British Birds c. 1797

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, woodcut, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

woodcut

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain

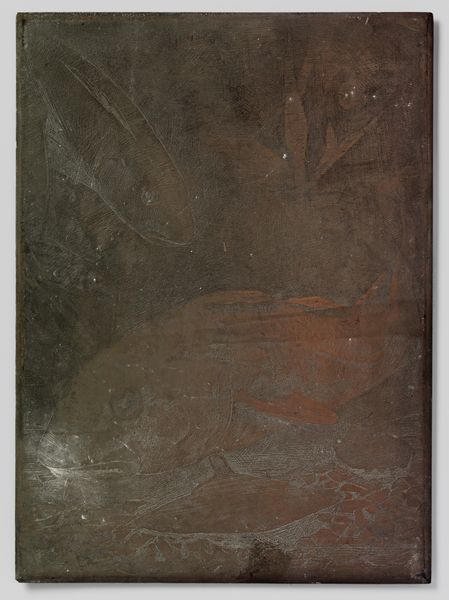

Curator: Here we have a woodblock for "The Swallow, from A History of British Birds," created around 1797 by Thomas Bewick. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the raw texture of the wood itself. You can practically feel the grain and the cuts made by the engraver's tools. Curator: Indeed. Bewick revolutionized wood engraving by using a burin on the end-grain of hardwoods rather than soft woods. This allowed for finer, more detailed lines and the ability to create tonal variations, emulating the look of a copper engraving. This printmaking method marks a shift in how we viewed the natural world at the turn of the century as industrial methods started reshaping our planet. Editor: The fact that it’s a block, an object used for *making* the art, and not the finished print itself, is so appealing. It reveals the labour, the deliberate removal of material required to conjure an image. It's like holding a little piece of the artist's intention, the work that would’ve otherwise remained hidden away in some drawer. Curator: Precisely. And this intention extends beyond mere artistic skill. Bewick's "History of British Birds" wasn't just a catalogue, but also a commentary on rural life and a reflection of the changing relationship between humans and their environment as labor conditions started deteriorating following the beginning of the industrial revolution. The book also targeted mass production and literacy. Each illustration offered a degree of scientific accuracy previously unseen in popular bird guides, fostering education across a broader readership. Editor: Considering that background, this dark, almost brooding swallow perched there carries an unusual weight. It isn't just a depiction, is it? The smallness of the bird against the dark background hints at vulnerability but the sharp precise carvings are powerful—it has a spirit of resistance, of life finding a way. I would almost consider it Romantic, a reaction against what that kind of rapid industrial development implied for a preindustrial and nature-centric worldview. Curator: Perhaps it’s a melancholy optimism, reflective of the social consciousness during Bewick's era. Editor: That's really got me thinking about how closely art is intertwined with socio-economic factors. Curator: A crucial element often overlooked, reminding us how art shapes and is shaped by the structures surrounding it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.