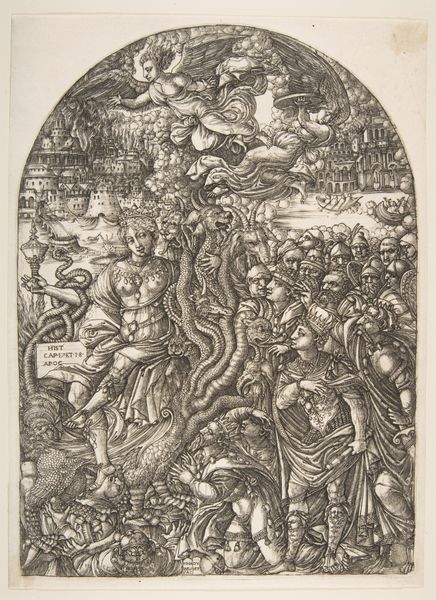

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

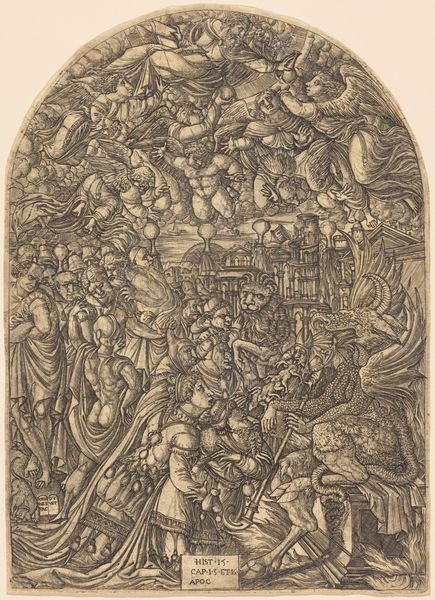

Curator: This print, titled "Mars," was created in 1534 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari. It's an engraving, dense with allegorical figures and violent action. Editor: My immediate impression is of overwhelming chaos. It feels claustrophobic; all these bodies packed into one space. The details are so intricate. What's drawing my eye is the stark contrast between the carnage below and those airy clouds above. Curator: Indeed. The density you mention speaks to the labor involved in its creation. Each line etched into the metal plate required meticulous work. Consider, too, that the act of printing itself made this imagery widely accessible. Think about how its production enabled broad dissemination of a pro-military and maybe propagandistic theme during a period of constant conflict in Renaissance Europe. Editor: Absolutely. This image is rife with narratives of violence, power, and masculinity. Looking at the central figures engaged in combat, it's impossible to ignore the hyper-masculine ideals being presented. Who benefits from the normalisation of this violence, and what social structures is it reinforcing? This composition aestheticizes conquest but fails to reflect the devastating human cost that the subjects had no control over. Curator: Precisely. The figures below – writhing, fighting, dying – their forms and interactions reinforce the power of the patron or intended consumer by creating what one could call the ultimate martial performance, made palatable through refined engraving and multiplication. Consider that at the time the original designer was publishing pamphlets, political announcements, literature and erotica in Italian and Latin. Who could afford this luxury? Whose point of view are we truly getting? Editor: And what about the women present? Some are clearly distressed, others clutch children as they watch on in dismay. Their relative powerlessness further highlights the entrenched social order and perhaps warns against its disruption by framing "chaos" with the horrors of conflict. This kind of image likely contributed to very real anxieties of the era. The family unit suffers greatly. Curator: An astute point. One thing that really sticks out to me is how printmaking technology had an inherent scalability, but one still delimited by expertise and expense. Access may be increased versus, say, painting, but it still depended on certain socio-economic conditions. So these political, patriarchal, allegorical sentiments spread through certain privileged tiers of society. Editor: This print is so rich in detail and fraught with the complexity of the historical narratives that gave rise to it. Thinking critically about whose stories are prioritized offers a strong point of departure. Curator: Right. By paying close attention to its material production, circulation, and reception, we can unearth insights into the artwork's complicated meanings, in its own era and still resonating today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.