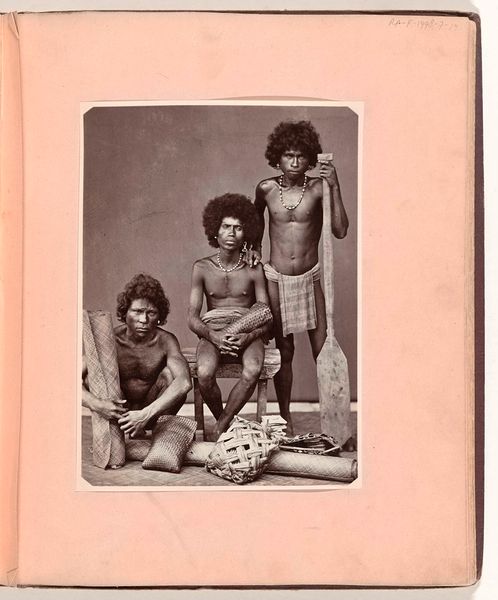

photography

#

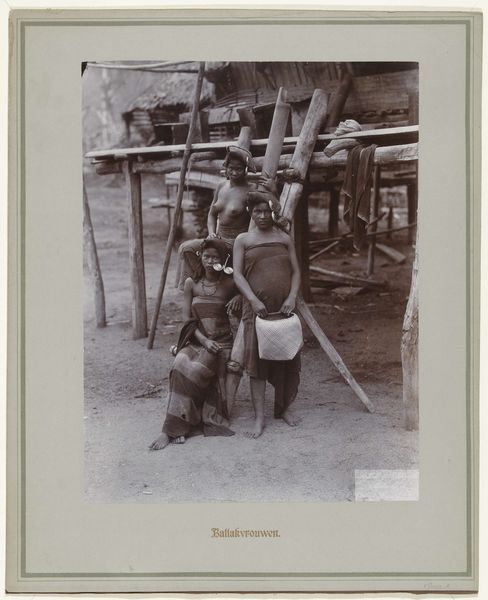

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 163 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

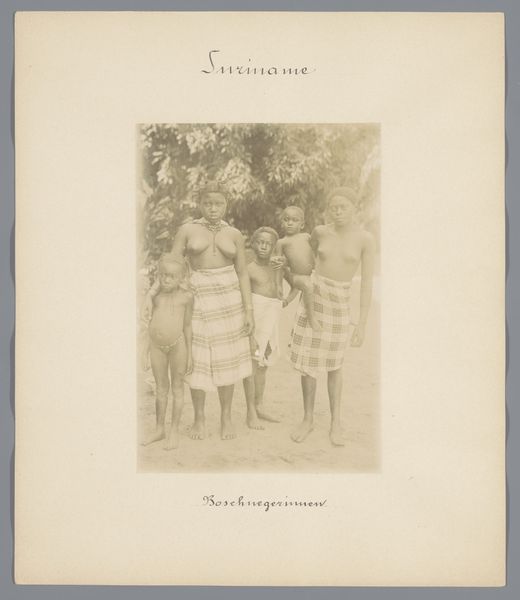

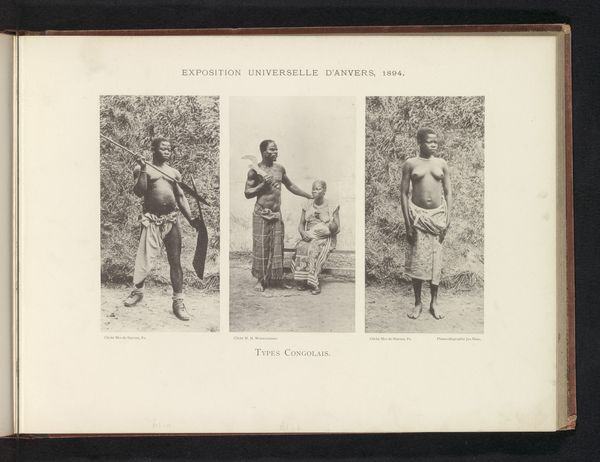

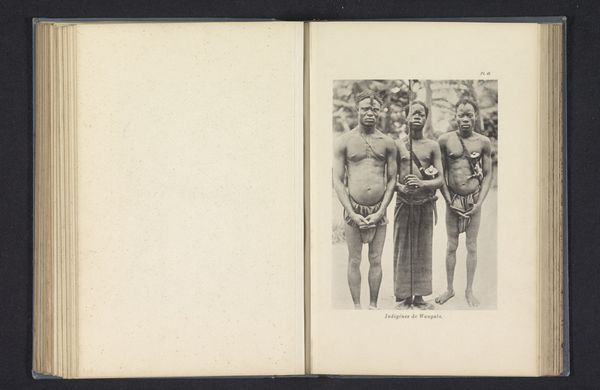

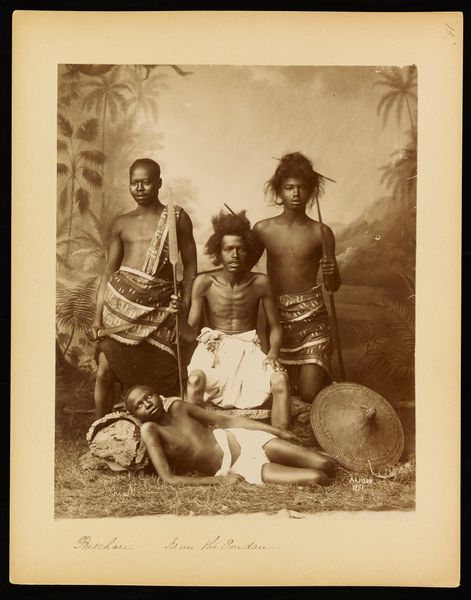

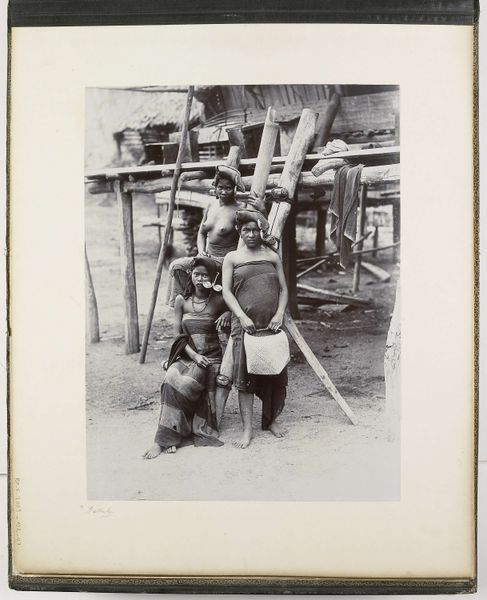

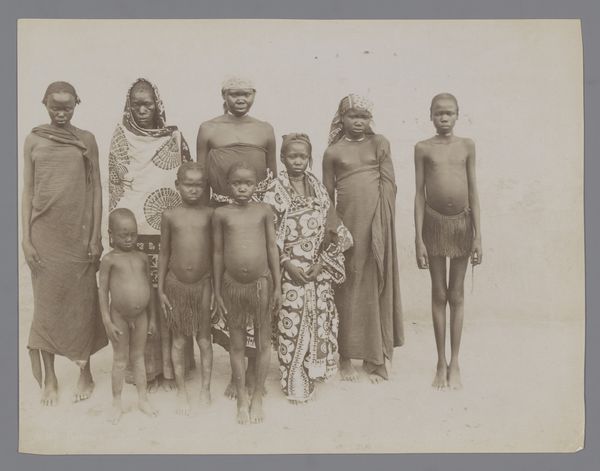

Curator: Looking at this gelatin silver print, one feels the weight of its historical context. The work, titled "Drie Surinaamse vrouwen en een kind," was captured between 1900 and 1905. It is currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is of a straightforward, almost ethnographic composition, the way the sitters are arranged reminds me of certain staged photography done for anthropological research. There's also something incredibly intimate in how directly they gaze. Curator: You know, the direct gaze is common in the Realism art movement; however, its employment here by photographer Eugen Klein begs an interesting social question, in light of both Klein's place as the colonial photographer, and that of the sitters, photographed here in what might today be considered a demeaning "othering". Editor: Indeed. Visually, those necklaces jump out. These women seem to share common symbolic ornamentations in these neck pieces and arm bands—these elements signal their culture's memory. The details around their bare midriffs feel less about "nude" aesthetics, but perhaps suggest everyday habit. Curator: That cultural aspect of indigenous dress practices makes perfect sense within Klein's production setting, although that setting itself bears significant meaning: How does one "curate" one's own representation for an obvious outsider audience? It might mean adopting a role as an indigenous cultural emblem. Editor: So it becomes both a portrayal and a performance. These pieces around their necks can represent everything: cultural survival and resilience under external gaze. They tell us, "we are here and visible and thriving". Even if the image is used to present Surinamese people a certain way, those visual markers claim something. Curator: Absolutely. That dichotomy – how this photography walks a tightrope between objectifying gaze and enabling a sense of indigenous agency. Editor: It seems to say so much about image consumption—how these pictures can evolve meanings, far exceeding what may have been the photographer's initial intentions. Curator: The image is, in the end, a product of complex circumstances, and its display can be interpreted through equally varied lenses, allowing us to perceive the depicted community beyond how early twentieth-century Westerners consumed it. Editor: And to reflect on how our understanding of symbolic representation and visual power shifts as we confront photographic relics like this one today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.