photography

#

pictorialism

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

nature

#

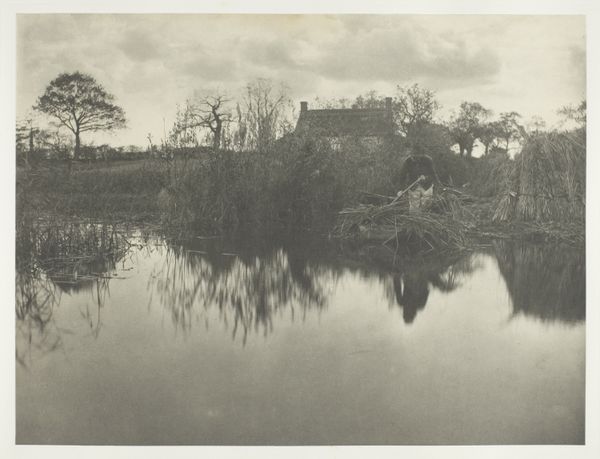

photography

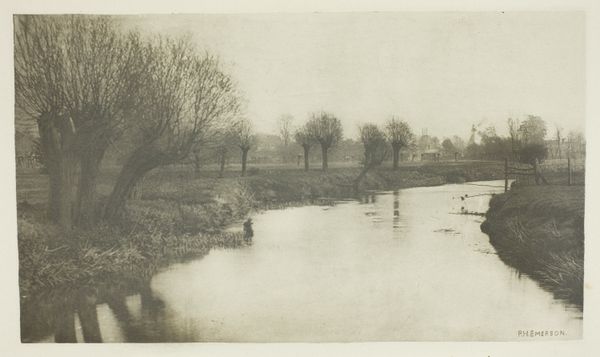

Dimensions: 12.5 × 20.1 cm (image); 15.4 × 22.3 cm (paper); 24.3 × 32 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have Peter Henry Emerson’s “Mouth of the River Ash,” a photograph from around the 1880s. It feels very atmospheric, almost painterly with its soft focus. What strikes you most about it? Curator: It’s the very act of photographing the everyday that captivates me. Consider the material conditions. Photography was evolving, becoming more accessible, yet Emerson consciously uses it to depict rural labour and its relationship to the land. Notice how he doesn't idealize the landscape, but shows it as a site of production, intertwined with the livelihoods of those who lived there. How does that influence your perception? Editor: I hadn't really thought about it that way. I was focused on the aesthetic, the misty atmosphere. The materials...you mean how the photograph itself was made influenced the subject matter? Curator: Precisely! The photographic process—the glass plate negatives, the printing techniques—demanded a certain engagement with time and place. It wasn't just about capturing an image; it was about documenting a way of life, a mode of production tied directly to the river, to agriculture. Emerson, like Millet with paint or Courbet’s stone breakers, puts the representation of honest labor front and center, but instead uses photographic technology. Think about the laborers that pose as trees. Are those forms chosen for that aesthetic or perhaps readily available on location. Do you think that Emerson challenges or reinforce traditional hierarchies within the art world? Editor: I guess both? He uses photography, a relatively new and accessible medium, but aims for fine art status. It's interesting to think about the materials and processes as driving forces behind the artistic choices. Thank you, I’ve got so much to reflect on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.