photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

16_19th-century

#

photo restoration

#

pictorialism

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

natural light

#

photography

#

england

#

gelatin-silver-print

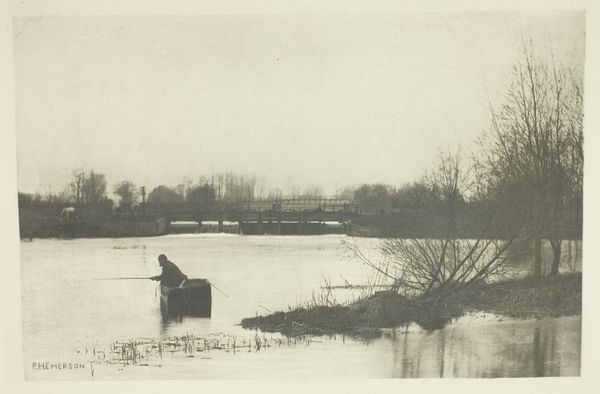

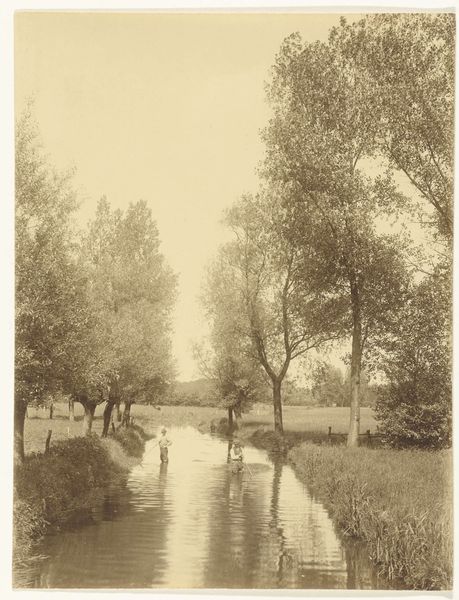

Dimensions: 11.9 × 19.7 cm (image); 14.7 × 22.2 cm (paper); 24.7 × 31.8 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

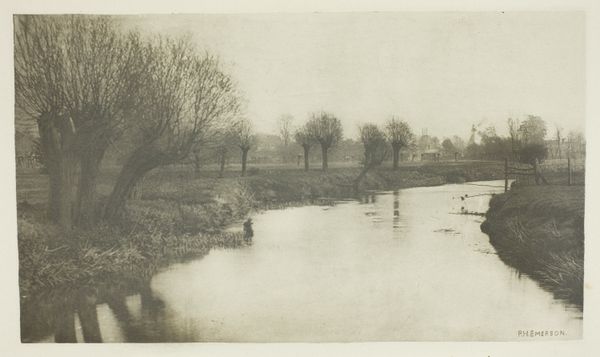

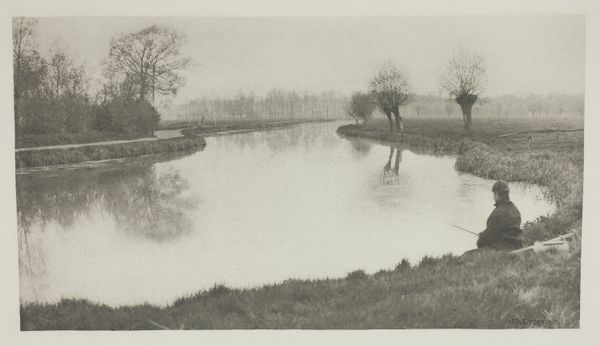

Curator: What a wonderfully muted and serene image. It whispers stories of rural life. Editor: Yes, it feels incredibly still, doesn’t it? It’s got this sepia dreaminess… makes me want to grab a sketchbook and just breathe. Curator: This is "The Shoot, Amwell Magna Fishery," a gelatin-silver print dating back to the 1880s, currently housed right here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Its creator, Peter Henry Emerson, was a key figure in pictorialism. Editor: Pictorialism... Right! So, not just about capturing reality, but shaping it, lending the photograph an artistic flair. That softness around the edges really sells that. It reminds me a bit of Impressionist paintings, the way the light kind of shimmers. Curator: Exactly! Emerson championed photography as an art form, seeking to elevate it beyond mere documentation. Look at the careful composition; how the trees frame the scene and guide our eye towards the lone fisherman on the small boat. He argued that photography should represent nature as perceived by the human eye, not with sterile sharpness, but with a degree of blur. It challenged prevailing scientific and industrial narratives dominating visual representation. Editor: It's funny how something so seemingly simple – a figure on a river – can carry such weight. Thinking about how radical it was at the time to see photography treated as *art,* to see it exploring mood and atmosphere. I love how it makes me feel calm, nostalgic, a little melancholic, even. Curator: Absolutely. Considering the broader socio-political landscape of the late 19th century, where rapid industrialization transformed the English countryside, works like this become poignant visual commentaries on the changing relationship between humanity and nature. It harkens back to earlier representations and romanticized pastoral traditions, subtly questioning the perceived progress of the time. Editor: It really makes you consider what "progress" really means, doesn’t it? Thanks, Emerson, for giving us pause. It really lets the quiet sink in, doesn't it? Curator: Indeed. A poignant reminder to engage with art, with history, and with the land around us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.